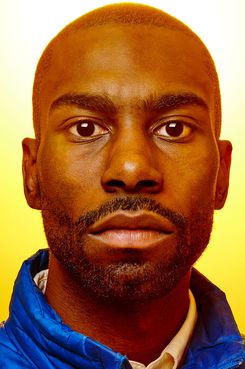

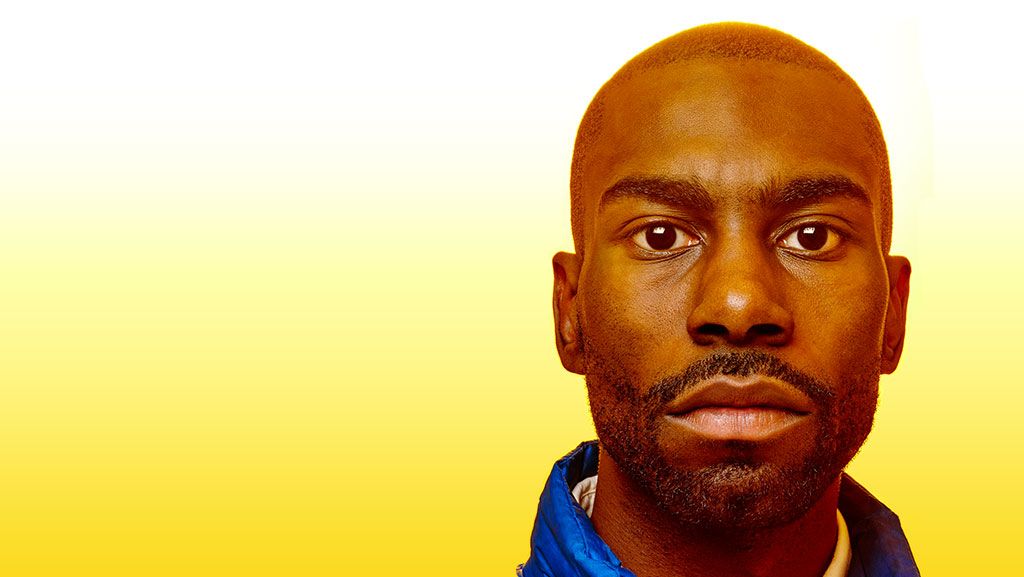

In Conversation With DeRay Mckesson

The activist talks about the new civil-rights movement, conspiracy theories, and that blue vest.

THIS INTERVIEW was condensed and edited from three conversations, the first conducted November 10, the second November 15, and the third November 17.

The day I met DeRay Mckesson was one of the more memorable days of my life, although that had little to do with meeting DeRay Mckesson. On March 7, 2015, I flew on Air Force One with President Obama and a number of other journalists as it made the journey from Joint Base Andrews in Virginia to Montgomery Regional Airport in Alabama, the first leg of a trip to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the bloody march across Selma, Alabama’s Edmund Pettus Bridge. The one wrinkle in this trip was that the flight was one-way, and by the time calm had again taken over Selma after a day of chaos, I rapidly began to realize I didn’t exactly know where I was staying, or how I was going to get back home.

Through Twitter, Instagram, and the archaic form of communication known as a phone call, I knew there were people I could reach out to in Selma. One of those people was DeRay. We’d spoken for the first time (via Twitter DM) only a day before, and his three messages contained an assurance that he’d like to connect in the Alabama small town, his cell-phone number (which I’d later learn was just one of his cell-phone numbers), and the words “I’ll have on my vest.”Mckesson’s blue Patagonia vest is essentially his uniform, verging on iconic status. Even the parody Twitter account @deraysvest has over 3,700 followers.

Before reaching out to DeRay, I texted an old colleague, Jay Caspian Kang, who I knew would also be in Selma. He responded “With DeRay,” and then announced he had a rental car. Later, when I learned that Kang was working on a New York Times Magazine cover story largely focused on DeRay, his co-protester Johnetta Elzie (“Netta”),Elzie and Mckesson met in Ferguson and have become side-by-side partners in protest. and a civil-rights movement that gained traction on social media and then moved to the streets, I realized that not only would I be meeting DeRay, but I also might have found my ride out of Selma.

Over the eight months that followed, DeRay’s fame grew in a manner unprecedented for an activist. From showing up at protests from Charleston to Baltimore to Minneapolis, to getting an audience with multiple presidential candidates, to increasingly having the ear (or eye) of those in many corners of the social-media-consuming public (from the followers to the haters to the famous), his impact in 2015 has been undeniable. I became a daily spectator of @deray’s life — the tweets, the news stories, the conspiracy theories about his life, the images of protests, the calls for his silencing, the occasional moments of carefree calm — with the occasional in-person DeRay Mckesson encounter mixed in. As I learned that online and offline DeRay (as well as on- and off-the-record Deray) weren’t terribly different, my fascination with his life only grew. Watching the worlds of our friends and colleagues increasingly overlap — in the way black people of a certain age’s lives often do — my interest in his actual week-to-week, day-to-day, minute-to-minute only intensified.

Over the last couple of weeks, while DeRay was in (and then out of, and then in again) New York for a stretch of days, we conducted the following conversation — part over lunch, but also via many DMs, texts, emails, mutually missed and/or screened calls, and finally, one successful phone call after DeRay traveled to the University of Missouri to advise student protesters.

So your home base is Baltimore right now? What’s the longest stretch you’re stable? When’s the last time you were in one place for, say, three weeks?

Wow.

Pre-Ferguson?

So remember when I moved to St. Louis for a little bit?McKesson left his job as a school administrator in Minnesota on March 6, 2015, to become a full-time protester. I was there for a while. Freddie Gray was April, so I was there for the month of March.

You definitely quit before we met in Selma?

Yes. And I drove all my things to St. Louis. So I was probably there for the longest uninterrupted time. And then was in Baltimore for a whileThis stint in Baltimore was during the protests that ensued after Freddie Gray died while riding in a police van on April 12. without travelling, May and June. But recently I’ve been going a lot more places. When Netta was at Amnesty,Elzie worked at Amnesty International in St. Louis before also becoming a full-time protester. I was the one who went to all the protests. But now that she’s not at Amnesty, we can sort of tag-team. And we try to be thoughtful about the fact that we don’t always need to be physically there, to use our platform to amplify the work of other people, you know?

That does diminish what could be complete overexposure. Helps you avoid the “chasing bad stories” narrative that many civil-rights leaders (old and new) have been associated with.

So we’ve been in touch with the students at MizzouStudent protests over racial tensions at the University of Missouri in September and October 2015 included a hunger strike and a number of black football players refusing to practice or play until the university president resigned (which he did). from early on.

What is it about what y’all have seen from the Missouri student body that’s striking?

What stays with me with regards to Mizzou is seeing them think about demands about the holistic student experience. I also think it could be groundbreaking on the student-athlete experience. The Mizzou protests have reignited activism on college campuses. And what we will see is a coalition of college students emerge because of Mizzou. And there’s incredible potential there. The Mizzou students are the true embodiment of the Ferguson effect, people believing a better world is possible and fighting for it — there’s no better example than the students at Mizzou. A belief that the college experience can be better than this. And that they’re willing to fight for it. That they’re clear about the fight. They understand that they’re learning and growing, as we all are.

And we’re in touch with the students at Yale.Protests began in November 2015 at Yale University following a racially charged incident at a Halloween party and an email about tolerating offensive Halloween columns sent by a faculty member. And like, if they say they need you to come, we’ll figure out how to get there. But we’re not just going to show up.

What would “need” entail?

More want us to come, not need. I think about when I went to Charleston.Mckesson went to Charleston after the June 2015 church shootings at the Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church. I have a platform and I can help. I can be in spaces that reporters will never be in because I’m a protester. But it’s also trying to offer advice and strategies. In Charleston, I’m close to the protesters there and spent a lot of time thinking through stuff. I’ve been in protests in several cities, the extended protest in St. Louis; we all learned a lot.

So the debate over free speech and protester demands that's been reignited in the wake of the Yale and Mizzou stuff, and the Amherst demands, etcetera. What's your take? The idea that protesters are silencing others or enforcing their worldview? Do you think the free-speech issue is a distraction?

The debate over free speech that has emerged in the context of Yale and Mizzou is code for the idea that all ideas are to be afforded equal merit. It's code for this notion that there should be a 50-50 split for how we discuss topics. But I don't think that discussing the benefits of slavery, for instance, is to be afforded the same merit as discussing the ways to end the impact of slavery.

Students are protesting in order to create spaces that promote dialogue and rich conversation. They are protesting to bring the First Amendment to campus in ways that actually speak to and acknowledge the black experience. I think that what's challenging for some people in the current context is that we are witnessing the necessary uneasiness of intellectual discussion happening in real-time. But communities are better when different viewpoints are put forward that allow for deep discussion. Tension isn't necessarily negative. The tension is the work.

To some degree, what you are doing is simultaneously selfless and a privilege, in the sense that there are people who want to be out there every day, but just have a nine-to-five and can’t. So it’s as if, at times, you’re speaking on behalf of those people who want to be there. But it’s also a privilege to be able to do it.

We’re trying to be a reminder that they’re not alone. We are representing all the people that can’t come, and we stand with you. And we want you to know there are so many people that support your work. We’re also doing it on Twitter, we’re telling these stories. We’re meeting with people, meeting with the protesters. The Mizzou football players reached out. So we had this text chain with like three black football players, with me and Netta — we’re trying to figure out how to support them, they’re trying to figure out things. Hopefully we’ll have a call tonight — but those are the things that people never see. They think that I’m just going to Mizzou. The guy doing the hunger strike,The University of Missouri student Jonathan Butler went on a hunger strike from November 3 to November 9, ending it when the president of the university resigned. we’ve had long conversations with him in his DMs about this and that. Same with the Yale kids. Like, we know all those people.

There are these interesting negative myths that come out about how we choose to operate in this space, given our visibility. People don’t fully realize we’re trying to leverage that visibility to create space for other people. The movement is bigger than me, I’m the first to say that, and we all have a role to play in the movement space. So just trying to figure out how to do that in a way that honors the fact that everyone has a role.

In April, you and Netta and BrittanyBrittany Packnett, an activist and Teach for America Executive Director in St. Louis, launched the initiative Campaign Zero with Elzie, Mckesson, and Samuel Sinyangwe. and Jay Kang gave me a ride out of Selma so I could get closer to Atlanta. That was the first time we’d met. I felt like in those first 30 minutes, there was skepticism about me, as a member of the press, and I’ll be the first to say I had skepticism, about you all as “Twitter activists.”

Yeah, but mainly we were tired of everybody that day and Netta was like, Who is this guy? Why is the backseat all squished up?

But you do acknowledge that press is inherently risky to do, especially when you can control so much of your own narrative via social media. How do you decide what to do?

I think it’s more about being thoughtful. The student newspapers are as important to me as the New York Times. And a ton of people have my cell-phone number. I try to be available, even if it’s just to talk through things. Not on the record, but just if someone wants to think through some stuff. And also trying to link people with people. Also, typically, when I do interviews, it’s like — I’m a Twitter person, so I’m a short-sentences, repeatable-phrases, make-you-work-for-it type of question-answerer. I’ll ramble with you, but normally it’s like, you ask the question and I’ll answer the question.

When we spoke on the phone last week and I asked you to do this, one of the things you said was, “People really don’t like me.” My immediate, knee-jerk response was, “People like you.” But then I remembered that I’d been on Twitter most of the day, and a lot of people really don’t like you, because you're a protester, an “agitator,” one that “disrupts.” How do you deal with that?

I’m fine.

Are you?

I’m thankful for my friends and their love. That’s real, to me. I have incredible friends, they’re incredible people. Sometimes, the hate that I endure is not necessarily about me, but about the space I’m in.

People need a target. And sometimes that ends up being you, or your partner-in-protest Netta. It’s hard to prove to people that you aren’t in it for the wrong reasons. Some people assume you’re only interested in causing trouble, others assume you’ve sold out. Either people don’t support your fight or don’t support the way you’re fighting. We do live in a fame-hungry world, so it’s hard sometimes for people to be convinced that you’re ever-present, but not doing it for the shine of ever-presence. Do you ever find yourself controlling your exposure? Needing to pull it back?

I’m hypervisible. So when you were like, I want to do this story, I was like, Lord. Netta and I use that visibility to try and create that space for other people — and to push this work — and I think people misunderstand that. So people see me in Silicon Valley and like, I’m hanging out with Jack,Jack Dorsey is Twitter’s CEO. Mckesson was invited to the Twitter headquarters in San Francisco to take part in a Q&A. and I’m talking to him, we’re having a conversation about Twitter and how I think the platform should go. I’m giving them this sort of feedback, you know — we’re trying to use it but it sometimes doesn’t look like y’all care about black people, right? Or what does it mean when Twitter’s only public ad is about baseball?The company’s first television spot was about baseball, and premiered during the World Series. The platform is such a powerful platform and baseball ain’t it. That’s not it.

One thing I’ve noticed about you is that despite all this criticism, you don’t really curse in public.

I don’t. That’s why Netta is holding it down.While Mckesson tends to be polite on Twitter, Elzie will sometimes bluntly call out people she disagrees with. She is holding it down for the people while I am — where I’m like, You know, I think we need to be more “whatever” about this. A reporter tweeted something at me today and I almost wrote, “If I didn’t believe in God, this would be a different tweet.” But I had to hold myself back from just going all-in on this man. I could not ask for a better best friend and protesting partner. And lord knows we have gone through a lot. We met at the first medic training in Ferguson, and then we knew each other because of Twitter.

How did you get to Ferguson in the first place?

It was 1 a.m. on August 16, 2014, and I'd seen the events unfolding in Ferguson via Twitter. And I waited until the morning and then called my best friend and asked him for his advice with regard to going down to St. Louis. I packed a small bag, put a status on Facebook saying that I was going and asking for somewhere to stay in St. Louis. Then I got in the car, drove nine hours, and ended up on West Florissant.

How did your protesting life start?

I went to Ferguson initially to bear witness — to compare what I was seeing on TV and Twitter with what was happening in person. I became a protester when I got teargassed for the first time, for simply demanding justice regarding the murder of Mike Brown. And you know, it was illegal to stand still in St. Louis during the fall of 2014. I'd never experienced the depths of a corrupt system like I had in those early days last fall — it simply wasn't the America that I thought I knew. In those moments, I made a commitment to confront and disrupt until we are able to build equitable systems and structures that support life, and until we are able to end police violence.

Was Ferguson your first protest?

I think of protest as confrontation and disruption, as the end of silence. And in that sense, I'd been deeply engaged in protest work on issues of educational equity for my career.Mckesson worked in both the Minneapolis public schools and the Baltimore public schools, in addition to being a Teach for America alum. But in terms of being in the streets? Yes, Ferguson was the first time I'd put my body on the line in order to confront and disrupt systems of oppression. I often think that, in blackness, we are all "on the front lines" — that we are all in proximity to the trauma of the state.

I'll never forget the woman who brought her grill out every day in those early days to make hot dogs and hamburgers for protesters, or the people who made sure that everyone had water. It was in Ferguson that I began to understand that protest is also community-building, literally bringing together people to form new communities of power.

How does one learn how to protest? Were there past examples you learned from? Something — like Occupy, perhaps — or someone you took cues from?

For so many of us, protest — the act of confronting and disrupting systems whose impact is oppression — is a way of life. We did not invent resistance and we did not discover injustice last August. We exist in a tradition of struggle.

The history of protest in America is strong, especially in blackness. Some chose suicide over enslavement in a refusal to allow their bodies to be used against their will, some decided to sit-in at Woolworth's to confront a deeply entrenched system of segregation, some chose to stand in streets to disrupt the normalcy of state violence. You don't learn to protest; protest is the response to the experience of injustice. You learn to sustain protest, to build coalitions, to think creatively about tactics. Diane Nash and Bernard Lafayette,Nash and Lafayette were influential leaders in the civil-rights movement of the 1960s. for instance, have provided invaluable feedback about protest and coalition-building.

So many of your moves are under constant scrutiny, or at least critique.

I don’t accept money to write articles. When I speak places we don’t negotiate the fee, like there’s no —

You take what you get? What’s the background on that philosophy?

Because there’s this thing — I feel it would become a thing where it’s like, I demand this amount of money to show up. In reality, I’m showing up because I believe that I want to spread the message and do my part. The movement is bigger than me and I believe that. For me, I used to think making more money was going to be this life-changing thing, and it isn’t.

When I started making more money, I just stopped overdrafting as much. That’s about it.

But now that I’m not making what I used to make, my relationship with money is very interesting. I don’t have a car, I don’t have an apartment.

Because so much of your life is on Twitter, it is interesting that I can be a spectator in your life.

I’m verified on Instagram now.

Verified is not the look. Why’d you get verified? You’re not verified on Twitter, wait you are … When did that happen? Why?

I didn’t do it.

Not verified is the new verified, man.

It just happened.

Sure thing. Okay, so what is the movement that you keep referencing? Whom and what are you talking about?

The movement is all of the people committed to confronting and disrupting systems that are oppressing people. I think the #blacklivesmatter hashtag has provided an easily accessible way to talk about a broader space and that is powerful. I think the movement is many people, many organizations, sort of with a shared goal of ending oppression at large, seeking equity and equality. Did you see the GLAAD speech I did?

I didn’t.

I talk about this idea of there being danger in the either-or, when protests become either in the streets or nothing at all. And I get that protests are so many things. If you don’t need to be in the streets because you can go to the governor’s house, go to the governor’s house. But I do think the movement is a space of people who will no longer accept the status quo, and are saying enough is enough, and are willing to put something on the line, whether it is putting your body on the line, your time on the line, your comfort on the line — that’s what I think about the movement space. And there are some organizations that are doing that, some people that are doing that. There are groups of people that are doing that that aren’t organizations, and I think the hashtag has provided an easily accessible way to talk about it.

You and Netta have been aligned for some time now, even if it just began as two people who seemed to be on the same page, communicating publicly and presumably communicating even more behind the scenes. Have things gotten easier for you since you all formed an organization?

What’s our organization?

Your website We the Protesters.We the Protesters is a resource portal for information concerning protests nationwide, and in some ways, the name of a group that exists within the #BlackLivesMatter umbrella.

There’s a difference between organization and infrastructure. So what we saw last fall was that infrastructure emerged. There wasn’t one organization that emerged that said, Here are the tweeters, here are the livestreamers — it emerged. And there was a system of the way people communicated, through Twitter. A set of informal rules that tied people together emerged. I think there’s something really powerful about that, so that’s one thing. And I think, for so long, Netta and I have been trying to think about how to create infrastructure and support infrastructure so people can do the work that matters to them.

And is it doing your work? Or just work in general?

It’s figuring out if there’s a way to organize that is as powerful as any other way to organize, that isn’t based around a membership model. So, people weren’t members of an organization last fall, and they did work. And there’s something to that that’s really powerful. And an infrastructure actually emerged — like, you could get arrested and the bail fund would be there. There’s an organization supporting the bail fund, but there’s also livestreamers and all these people that sort of came together, and the coming-together wasn’t an organization; this infrastructure emerged. Is there a way to take the spirit of that?

So when we did We the Protesters, it’s like, all the chants in one place. If you’re a protester somewhere and you don’t know the chants, we know the chants because we remember the first time people said them. But how do we help you get that infrastructure? It should be simple. We think our Campaign Zero — we’re saying these are the ten things we think will end police violence at a structural level. And we believe that all ten of them together [are essential], not one alone. But we also know that you probably care about buckets four and six, and that’s it. So how do we create a space for you to plug into those because that’s where you want to fight? So we’re really interested in the infrastructure. And remaining nimble.

It feels like this way there’s a lot less of the red tape that is typically part of the deal with organizations.

And it seems true to the space that brought us together. There was no committee that started the movement. There was no email saying, “Come outside.” That wasn’t it. It was just people coming outside. Organizations have emerged and they do powerful and important work. This is not an either-or conversation. This is — how do we continue to push organizing in spaces to think about the work differently? We believe in the power of digital organizing to create infrastructure. And we understand infrastructure and organizing to be similar but not the same. Does that make sense?

Yes. Also, I’m so glad you didn’t wear the blue vest today.

The down is coming out.

I think it’s time to ditch the blue vest.

It makes me feel safe.

Why aren’t you wearing the blue vest?

I need the down replaced. So far, Patagonia won’t replace the down.Update: The vest has now been patched up.

What about a gray turtleneck?

It makes me feel safe. Actually, can I tell you what I want to talk about? I want to take a shower. And I’m trying out these new glasses, because I bought them. So now I can look at myself in the mirror now that I got a haircut.

It’s a good lineup. I tend to tell my barber to avoid the hairline.

What do you want to talk about?

I want to talk about relationships. Actually, I want to talk about celebrities.

Influencers.

Sure. It’s a double-edged sword, being close with or interacting with celebrities that are trying to align themselves with you, learn from you, and maybe even seem socially conscious because they’re with you. But that’s new for you. And I assume you’ve had to learn how to deal with it. It’s a different world. A year ago you had not spoken to Beyoncé.

I still have not publicly spoken to Beyoncé.

She follows you on Twitter.

I knew you were going — okay, so, yes, she follows me on Twitter.

People took note of that.

People felt strongly, either way. She seems like someone who is actively working behind the scenes to support the movement. And I want to believe that the follow is a way to stay informed about what’s happening. Here’s the thing: There’s a recognition that we all gotta get free. Celebrities, not-celebrities, rich, poor — with blackness, we all have this relationship with trauma. The trauma looks different across some of those lines, but the trauma is there, the world treats us a certain way.

One is an acknowledgement that there is a shared struggle, across economic [status], across influence. So it’s not enough to only organize one part of our community; we got to organize the whole community. I believe that. The second is that sometimes I worry that we have mastered how to talk to the choir. That we have become the best choir masters, as opposed to bringing people to the choir. So I think of these people with these large platforms.

It’s about how you let people even know where the church is.

Right. Like, how do we do that? People with large platforms who don’t traditionally talk about these issues but either care and/or live these issues can help bring people. And I think there’s something really powerful about that. So like a Jesse Williams,The Grey’s Anatomy actor has long used Twitter as a platform to discuss the various inequities in society. he chooses to talk about these issues because he lives in a world where his blackness shows up and that is real, and he acknowledges that and understands the implications for that, and wants to use the gift of his platform to talk about these issues. And what I’ve found is that there are many people who are in a position similar to his who want to do that work but don’t know how.

Who are those people?

I can’t say on the record because they don’t want to be the “I don’t get it” celebrities. That’s awkward …

Fair. Well then, ones that you speak to with some frequency, that you think do “get it”?

We often build our communities with people who share our values, beliefs, and sense of urgency. Twitter has fundamentally changed our sense of "community" in that it’s now much more expansive, much more inclusive, than it historically has been — and this also means for all of us to connect with each other, including celebrities.

I think of it less with regard to celebrities I interact with, and more about being around people with whom there are shared values, beliefs, and a sense of urgency. And in that sense, Jesse Williams, Jussie Smollett, Rashida Jones, Talib Kweli, Matt McGorry, Harrison Barnes, and Gabby Sidibe are a few of the celebrities who deeply understand these issues of racial equity and equality and are committed to using their platforms to address these issues.

It is interesting, because I think a lot of people in the past two years, since Trayvon even, have had that moment — because I remember when it happened with me — the moment when you’ve long been vocal in one way, but you make a leap on social media and you say a few things and it’s almost like your cover is blown that you’re not some safe little boy or little girl that isn’t aware of the world. Something happens and you send that one tweet or write that one post — where it’s almost like there’s no going back, you have blown your safe cover that you are here for the status quo. I’ve seen that moment happen across genres, occupations, everything. I’ve seen people have their first black or racial or gendered or sexual-orientation awakenings on Twitter. People who have probably abandoned that lifestyle as their profile got bigger, but what’s happening in society and Twitter brought them back. I think many people are getting their cues from you, from Netta, from others. It must be kind of flattering in some ways, right?

It’s less flattering and more an acknowledgment that there is a shared struggle. And that we all have something to learn from each other. Like, we didn’t just wake up woke.Woke: Aware; able to sniff out the bullshit, at all times, because it’s all around you, the end. We weren’t born woke. And lord knows we learn every day how to create space, what is the space for people, for celebrities, for influencers, for anyone to also do that learning. If they learn in public and it doesn’t go well, they might do more damage to the overall conversation. That’s a bad way to say it — but learning is messy. For us, it shouldn’t be in public. I think about the conversations I have with my best friends, and they are not the conversations I’m having in public. I’m thinking through things with them; I’m not doing that in an interview.

You workshop things privately. Which isn’t so different from you, or Netta, going down to a college campus and talking to students about how to articulate their views.

Yeah, I’m trying to push these ideas. And how do we make sure that everyone in our community has space to do that stuff. So what I’ve found with my interactions with some celebrities is that they understand the issues, might not have space in which they can deal with the messiness of the issues, but want to use their platform.

I knew you were gay. I assumed that at this point that was very public knowledge, but I’m following you more closely than others. Have you found being a black and gay man in your space has been something that’s made your life more difficult? Have you seen support from some people decline after you came out?

One thing I said in the GLAAD speech is this idea that just because people aren’t shouting doesn’t mean they’re hiding. Or they’re being silent. The anchor of this speech is that some of us aren’t coming out of the closet, some of us came out of the quiet. Just because you didn’t know doesn’t mean I was hiding, right? And I believe that. Just because you might not know I’m gay doesn’t mean that I’m ashamed by it, doesn’t mean that I don’t talk about it. Being gay is part of my identity. My identity is more complex than just one thing. It’s been interesting in the movement space because some people are really homophobic, but like me, whatever that means.

You know what that means. You’re an exception to some terrible rule. Like a special gay. Gay asterisk.

But then others learn that I’m gay and then it becomes a way to explain everything they hate about me. That becomes the thing for them. Or there are people who learn and sort of appreciate it — and hope that the intersectionality of that will benefit the larger movement space. The day was in Jay’s piece. That was the first time it was in a public thing.

Didn’t realize that.

People called me a faggot on Twitter from like 8 a.m. to midnight. It was awful. That was not a good day. I blocked 16,000 people on Twitter. So, yeah, that was not a good day. But otherwise, so much of this work is slow, and slowly we’ll help people understand that “love is love” message. And what I’m not here to do is fight you about it. Not going to battle about who I love. But I am going to hold you accountable for the things you say that are meant to inflict harm.

You can’t truly be about the movement if you are pro-black and a gigantic homophobe.

Yeah.

You can’t check half the boxes.

[Checks phone] Oh, this is so sad. So this is how it starts. Netta must be going to a protest, this is always really sad to me.At this point, wasn’t sure if he was going to the University of Missouri. Later that evening he did, joining Netta.

Wait, what?

These are the texts — the “if she dies,” “if someone takes her phone,” “in case of emergency” — these are the texts we send to each other.

Are all of your Twitter notifications on?

Yep. I get a text for every tweet.Not every single time he’s mentioned, but when someone he follows mentions him — it’s still a lot.

Yeah, me too. It’s very dumb. Anyway, protect Netta at all costs. Next question, is being an online activist …

Is that what you just called me?

I was just seeing if you were on your toes.

Wow. Tell me how you really feel.

As an activist that —

I’m challenging the premise of this question.

As an activist that is on the move a lot and spends a great deal of time online —

What’s that got to do with me being an “online activist”?

Can we get past this flub so I can ask my question about relationships?

[Pause]

Have you been in any relationships since you began a life protesting? I have to imagine it’s difficult, if you have.

So I’ve been in one relationship since the protests started, that I’m no longer in. I travel a lot. Independent of that relationship, so much of my life is online — and we’re back to your dumb “online activist” thing—

So do you roll into a city and get on Tinder?

Can you imagine if someone saw my Tinder profile? That would be a story. “Deray, activist — looking for love.” No, no Tinder.

“In town for the night — just out here for the movement, and you?”

“Here for the movement … And you?” Got to get that on a shirt. No, no, none of that. But no knock, I support dating apps.

All these disclaimers, but you have to.

People would certainly be like, “Deray hates Tinder, all apps, dating.” I think sometimes it’s hard because people are like, who’s the real you? Like, you actually do know a lot about me if you follow me. I tweet a lot about my actual life. So I’m not like a secret person if we meet in person.

I spoke to Netta about this once — the world of public-facing people, heroes, mentors, people you looked up to — and getting closer to them as time goes on and subsequently being kind of disappointed.

I think if anything — I remember the people I emailed asking for support last year who didn’t say anything who now won’t stop calling me. I remember those people. And that’s interesting to me.

Do you have mentors?

I have a set of people that I go to for advice.

Is it an age and experience thing?

So, for example, I have Donnie, who isn’t a mentor, he’s my best friend. But with Donnie, we probably talk through all the big things that happen in my personal life, or if I’m trying to tighten a message and I need a sounding board, he’s that. I was the best man at his wedding, a really close friend. Netta, obviously. My father about emotional things, because he’s my father. My sister [TeRay] and I are really close. And then Robin, my second mother in Baltimore.

So you have an inner circle.

Yeah, and that’s just some. When I say I have great friends, I mean, if it wasn’t for these friends I think I would have lost my mind. I think about those 16,000 people I blocked. I had to consume the hate by the time I blocked you. I saw it.

It doesn’t get filtered into one folder where you can just delete.

I saw it. And that’s hard. That’s hard. The relationship thing — I’m hopeful that I’ll find a partner. A relationship in which I’ll be able to continue my commitment to the things I believe. And we can grow and learn together, I believe that.

So let’s talk about the world of the conspiracies that surrounds you. I felt defensive of you at first, occasionally feeling that need to be ignorant on Twitter on your behalf so you wouldn’t get caught up. But I feel like I remember you going from getting defensive to just highlighting it, showing people the type of stuff that comes across your desk every day. When did that switch happen?

Probably soap and Doritos.

[Laughter]

Please explain them.

So we grew up using Dove soap. But I tweeted that I use Dove soap. And it legit became a thing — he can’t be pro-black if he uses white soap. Dove soap started trending for like six-to-seven hours nationally. So that was special.

And you had to kind of make a statement.

Yes, I was like, “I’m not sponsored by Dove Soap, I believe in black people.”

“And darker soaps.”

“All soap matters” — but also Doritos.

What was Doritos again, I can’t even remember?

I tweeted about DoritosLet’s repeat: This was not an actual Doritos-sanctioned photo. and was like, “Whoever made this is creative. You win for creativity.” Kind of mocking it a little. I got Facebook posts about it, I got emails about it, I can’t believe you sold out for Doritos. For weeks. It was like, I’m not sponsored by Doritos. Also, I love Spotify.

What was that one with the Spotify Discover Weekly playlists? You’re definitely the Feds, because you tweet about Spotify.

People were like, “We know you’re sponsored by Spotify.”

Do you drink coffee?

I don’t drink coffee or soda.

Do you drink?

I only started drinking like two-and-a-half, maybe three years ago. Both of my parents were drug addicts, and my mother left when I was 3, and my father raised us, and one of the results of that was I’ve always been afraid about being addicted. So, I didn’t drink and I’ve never smoked and never did anything else. And then I was in Minneapolis and realized I was afraid of alcohol. And I didn’t want to be afraid of it, that was too much for me. So I started drinking white wine. I only drink white wine. And one glass of white wine and I’m like, talking really slowly. I’m like, Rembert, howwwww areeeeee youuuuuu? So, yeah, one glass. Because I have zero tolerance. Like negative tolerance.

You know what would be funny? If you got a white vest.

Oh, lord.

Has it been interesting to get negative feedback, negative support from white folk and black folk?

This is going to sound bad, in New York Magazine.

I don’t give a fuck.

Sometimes some of the fights don’t make sense to me. It’s just like, what are we talking about? I anticipated fighting people that don’t believe in equity and equality. I understood that as a part of the work. I didn’t anticipate how people who believe in equity and equality would also approach people in the movement with the absolute worst assumptions about everything they do.

When I went out to Twitter, I was invited by the Blackbirds, the black group at Twitter. Jack does the Q&A, and I come as a user of the platform. I reach out to LeslieLeslie Miley, a black Twitter engineer who left the company recently over diversity issues. and ask him about the climate, because he just left the company. And he is in support of me coming, so I come. He and I talk for three hours, he has not lost faith in Twitter [the company] as much as he acknowledged that Twitter has not lived up to its own commitments about race and equity. So I go, we have a good talk, I have a ton of feedback about the platform and how it can grow and how it can amplify voices of people of color.

I get on Twitter, online, and it’s like, “Jack just wanted to use you as a prop to talk about diversity.” “Why did he bring you to talk about diversity and tech.” “There are people who have already been doing this work.” And I’m sitting here like, I didn’t come as an engineer. You didn’t approach me with any questions. You did not ask any questions about what happened, you just assumed that I went. And that is hard for me. Because I’m sitting in the rooms, I’m in the meeting, trying to open up spaces for other people — I’m learning. I understand diversity issues in society and employment, but in the tech industry I’m learning. I’m not going there as an expert. Jack asked me zero questions about diversity and tech because it’s not my area. But I will use that space to say there’s clearly an issue. That’s why I met with Leslie, so I could understand more.

There’s two things. One, some people want reasons to be skeptical, forever. The other is that if there’s one hallmark in what happens on the internet in 2015, it’s that people are very easily bought off. You can get someone with perceived peak authenticity and then six months later, you see hashtag this, hashtag that on all their stuff. So some of it is you, some of it is societal skepticism. But also, some people really don’t want you to keep going.

When people assume that, it’s not solidarity to me. That’s hard. When they see pictures of me and Jesse [Williams] together. Or Jussie [Smollett, who plays Jamal Lyon on Empire]. Or Harrison Barnes [who plays for the NBA champion Golden State Warriors]. That I’m just hanging out. Or Reed Hastings [co-founder and CEO of Netflix]. I’m trying to have these conversations about race and build coalitions.

Wait, Harrison Barnes.

Yes, Harrison. Barnes was seen wearing a “I Love My Blackness. And Yours” t-shirt, proceeds going to WeTheProtesters.org, during a televised practice in October.

Great. Do you type out “I love my blackness. And yours.” every single time or do you have it on some forever auto-tweet?

I type it out.

Okay. Why do you have three phones?

I have one that is the number I’ve had since I’ve ever had a phone. I have a second phone, and then the trolls were finding people’s numbers and sending them to automatic dialers. So I didn’t want that to happen to the number I’ve had forever. But there was a period when a small group of hackers — they hacked into my email and they were trying to hack into my phones. So I got a third one —

How did you find out you were getting hacked?

Because I would get these emails that were from me to me. Or when I’d opened an email it’d disappear. Or there’d be these links — it was crazy. I had to talk to this hacking security group, so the third one is a pay-as-you-go situation. But, yeah.

Did people dress as you for Halloween?

Yeah, I saw a few.

So one thing you’re trying to help pull off is a #BlackLivesMatter town hall with the presidential candidates.

We are. I think there should be public space where people can ask questions. To both sides, Democrats and Republicans. We reached out to Rubio’s team, haven’t heard back. Reached out to Carson’s team, haven’t heard back. One thing we’re trying to solidify is a [televised] network partner. Twitter has already committed to being a partner.

As for the Democrats, beyond the town hall, you’ve met with both Sanders and Clinton. How would you compare the outcomes?

Both camps have been responsive. The challenge is that Clinton’s platform is still not clear with regards to race and criminal justice. She has subsequently released important pieces of policy related to mass incarceration.In October, Clinton released a justice-reform plan that addressed private prisons, mass incarceration, and other criminal-justice issues (including drug-related crimes) that disproportionately impact the black community. She rolled out some policy pieces, but there’s a host of other issues she has not addressed, and it appears that her strategy is one speech, one policy. That she will unveil, roll out things slowly — which is interesting. The challenge of that is we don’t know when we’ll be able to look at all of her policy proposals in relation to each other. We can do that with Sanders and O’Malley, but can’t do that with her now.

Do you consider getting these meetings or getting a town hall as a success?

No, something’s got to change. The meetings are a precursor to change, the town hall would be even more so, but something’s got to change.

I do think the next step that’ll happen in this world of activism is figuring out where else the influence is best felt. I do think the world of politics could be a ripe world for those good at activism, at mobilizing, at protesting. Is politics a pivot you think you’d ever make?

Working as a senior leader in two public-school systems changed the way I thought about politics. I saw the importance of what it was like to understand the details at such a deep level and how decisions made within the system often have immediate and sweeping impact. I managed a range of workflows, from staffing to workers’ compensation in the Baltimore City Public Schools, and there, I saw the power of what it would be like to be on the inside, fighting for change. And obviously in protests, I see what it’s like to be outside the system, pressing and fighting.

Many people have asked me if I’d consider running for mayor of Baltimore. And I think it’s — I don’t know at what point I’d think being an elected official would be the best way to be in the work, because right now we are trying to apply this pressure from the outside. And force systems to change and respond, forcing these conversations. I’m confident that protesters will run for office at the local level soon. And do transformative work. And I want to support that. And know protesters would be completely capable.