Early in the fourth Republican debate, Wall Street Journal editor Gerard Baker, one of the debate moderators, asked Carly Fiorina a question that cut at the heart of the rationale of every candidate onstage. Under Barack Obama, Baker noted, the United States has added an average of 107,000 jobs a month. Under Bill Clinton, it added an average of 240,000, and under George W. Bush, just 13,000 jobs a month. Economic growth is the ultimate basis for the entire Republican economic program — the inducement they can offer to explain why Americans should give up things like cleaner air, a higher minimum wage, and more generous social programs.

Fiorina’s reply had no point of contact with the question whatsoever. Indeed, she said, “Yes, problems have gotten much worse under Democrats” — the exact opposite of what the question had stated — before launching into a generic denunciation of the evils of big government. The basic case for changing parties turned out to pose an obstacle that all the candidates had difficulty surmounting.

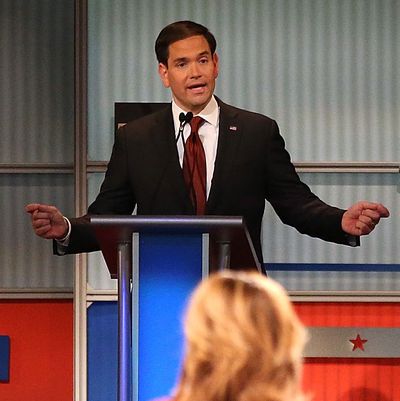

Neil Cavuto told Marco Rubio that he had called the last Democratic debate “a night of giveaways, including free health care, free college, and a host of other government-paid benefits.” Cavuto asked which of those giveaways he would take back. Rubio did not name any, instead launching into the story about his immigrant parents and his standard stump speech, portions of which he managed to repurpose for every question posed to him.

Likewise, Jeb Bush answered a question about how he would bring about his absurd target of 4 percent annual economic growth, and — after reiterating that 4 percent growth would be really great — promised to “repeal every rule” Obama has imposed on the economy. But if that would work, why didn’t we have 4 percent growth under the previous administration?

And when a moderator pointed out to Rand Paul that energy production has boomed under the current administration and asked for his policy response, Paul replied that he would repeal the regulations that have hampered energy production.

All the candidates prefer to live in a world in which big government is crushing the American dream, and all of them lack even moderately credible specifics with which to flesh out this harrowing portrait. The most successful efforts were made by the candidates who did not even try and, in their different ways, used personal symbolism in place of policy detail. The two candidates who do this the best are Rubio and Donald Trump. Rubio answers the question about changing America by framing the problem in generational terms. What’s wrong with America, he explains every single time he is asked, is that it is old, and what’s needed is something new, i.e., him. Trump has the exact same approach, only in his telling, every problem is a matter of losing, and the solution is to bring in a president who wins, i.e., him. Both the Rubio and the Trump themes can be adapted to any subject, and can be stretched to cover up for a lack of policy substance or even ideological coherence. The lack of socialist horrors to have materialized under Obama is not a problem when your promise is to be new or to win.

The candidates who found themselves trapped were those who attempted to connect Republican dogma to concrete economic conditions. Fiorina wound up her concluding remarks by stating ominously, “Imagine a Clinton presidency,” before unspooling a litany of horrors. But of course we don’t have to imagine. We had a Clinton presidency. And, as Baker pointed out to Fiorina at the outset of the debate, the economy thrived.

In a debate where chastened moderators avoided interruptions or follow-ups, the candidates were free to inhabit any alternate reality of their choosing, unperturbed by inconvenient facts. Presumably, the general election will intrude, and the nominee will be forced to make a stronger case against what looks, at the moment, like peace and prosperity.