Right now, it’s Steph Curry. He’s gifted beyond belief. At times, his movements resemble a seasoned dancer’s as much as they do a basketball player’s. And he’s cool, but in that way that he doesn’t have to say much for you to internalize his quiet self-assurance. Steph’s game is cool. The way his uniform fits is cool. The way he dribbles, shoots, passes, runs, and reacts to his own success is cool. That’s why it feels like we’re living through something special, because athletes like this are rare.

Before Steph, there was Roger Federer. At his peak, the power of his opponents was no match for his skill, his grace, his technique. But even still, the tennis phenom was powerful — and it was unclear where in his frame it all came from. He was intimidating in a way few tennis players have ever been, seemingly winning the match as he entered center court, often dressed monochromatically, with the perfect headband, the perfect sock length, the perfect Federer signature shoes, and the perfect ability to not sweat throughout an entire match. He was better than you — each opponent knew that — and despite all of his outward humility, he certainly knew it, too.

Perfection is hyperbolic, but there are moments when it feels like a fair assessment. With Federer and Curry, there is nothing jerky about their games, nothing accidental, no success via luck — it’s fluid, it’s clean, and it works with a precision that seems more mechanical than human. But that cool — the one thing that outshines the mechanics — is what makes their actions constantly feel heroic.

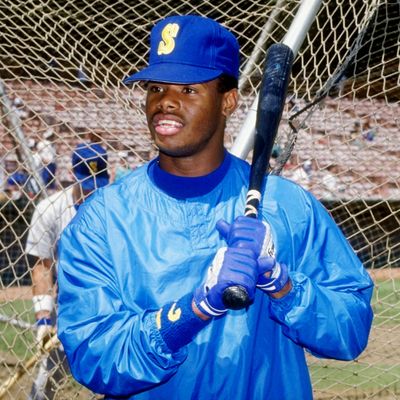

The first athlete to ever have this effect on me was Ken Griffey Jr. When I was a boy, he was the one thing that seemed flawless. He was a mythical creature, an unattainable being that, if you were young enough — with enough years to practice practice practice — you still hoped that being like him was your destiny. And it wasn’t just one or two things: There was the swing, the home-run-robbing grabs, the wall runs, his gait as he rounded the bases — but also his decisions to occasionally wear his jersey unbuttoned in casual settings, his backward hat at home-run derbies, or even the way the name “Griffey” looked on the back of a Mariners jersey, just slightly wider than the “24” that sat below it.

He was such a part of my childhood, which is not a fact unique to me. That’s a defining feature of an entire generation.

On a plane back to New York City on Wednesday, I saw people tweeting about Griffey. I didn’t know why for a few minutes, but I loved it — because he was my singular childhood hero, more than Jordan, more than Sampras, more than 3,000. Just as we took off, I saw the news. Griffey: Hall of Famer. And not just a Hall of Famer, or even a first-ballot Hall of Famer, but one with 99.3 percent of the vote — the highest percentage ever.

My guy was the guy. I couldn’t stop smiling. Suddenly I felt compelled to look up more — supercuts of swing videos, pictures of those classic Mariners teams, excited tweets from others who idolized him — but “no service” took over, and I was just stuck in 35E with my thoughts. So I closed my eyes and felt what it was like for memories to flood my head.

When my eyes were closed in that seat on the plane, I felt out of control. A mixture of thoughts from my childhood — some things I hadn’t contemplated in years, others I’m not sure if I’ve thought of since they actually happened, and a few that frustratingly may be wrong or completely imagined began to cloud my thinking as the plane ascended higher. The one common denominator: They all were related to Junior Griffey.

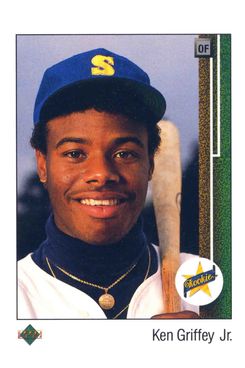

I used to collect trading cards growing up. Basketball was always the cooler sport, but somehow baseball still had the advantage in my childhood card universe. My mom would take me to this card store that, I think, was in Greenbriar Flea Market, a stretch of stores in southwest Atlanta, because I remember it being near or next to Eddie’s Gold Teeth, the iconic Atlanta shiny-mouth shop. Excited, I’d buy packs with whatever she’d give me — 5, 10, 20 dollars. Every pack of baseball cards I’d open, I’d hope there was a Griffey. I had plenty of Griffeys already — and nice ones at that — but I wanted more. To me, they were the only cards that weren’t tradable, but I’d still have a stockpile in the front of my card binder, so when I was at basketball or tennis camp and another 9-year-old wanted to see what I was working with, he or she would have to take me seriously, because first they’d have to flip through pages of the Kid.

I’d forgotten I used to trade cards at camp. It was what we did during lunch. It was my first experience at being a hustler, a shit-talker, someone with perhaps more assets in ’98 than I do now.

I also had a Super Nintendo, and I’m pretty sure one of the Griffey video games came with the console. If it didn’t, my mom bought it separately. I played it nonstop. One of the coolest things about Griffey games — truly making it known how next-level he was — is that he was the only actual MLB player in the game. They didn’t have any rights to anyone else, so they’d give nicknames so you knew who the other players were, but Ken Griffey was actually Ken Griffey. The greatest thing about this game is that somehow technology had advanced enough that there was a green-foam-bat hookup (with a very solid plastic core) to the game, so you could actually swing as the batter.

The game was in our living room. There were couches in the back of the living room, and one of those big 1990s entertainment units hulked against the opposite wall. It was like 16 parts and made of wood and took up a third of the room and had a space for your big, 200-pound television and a built-in space for CDs and a built-in space for cassettes and a built-in space for records and a built-in space for anything else that provided entertainment. Yes. We definitely had that. And I think the room was carpeted, because I remember not being able to hear the Griffey game or cartoons or music videos sometimes when my mom vacuumed.

The only thing I remember doing in this room was swinging as Ken Griffey with that bat. The pendulum swing, with the immediate dropping of the bat, followed by three or four dramatically confident steps, a little hop, and a run toward imaginary first base. And because this was years before the Wii, it took months to figure out the timing. I think you had to swing right as the pitcher released the ball, so the information of your swing would go through the wires and make it to the console and then to the video-game character in time to make contact. My most vivid memory involves a time my friend Jalé was over. And we were playing the game. And one of us nailed the other in the back of the head with the bat. I think he hit me — but I easily could have hit him.

For the first time, I recalled crying when the 1994 season went on strike, because Griffey had 40 home runs, with almost 50 games left to play, and I finally understood what it meant for the world not to be fair. I recalled walking up to the pile of sticks that was home plate with my hat facing forward, and then turning it backward — it was the baseball version of the Jordan tongue in my neighborhood. Shit, I did have a little front yard. And a neighbor. His name was Ant and he played all the same sports I did. We both had basketball hoops; mine was better, but I liked playing on his driveway more because of where the basket was positioned in the driveway.

I would even play ball in my Mariners hat, the dark blue one with the nautical S on the front. And it was fitted, because that’s what you got when you asked for money to spend at Foot Locker or Lids.

There’s only been one item that has traveled with me in every bedroom I’ve inhabited since leaving home for college: my Griffey 1989 Upper Deck rookie. I’ve always had a hard time getting excited upon receiving gifts, which in turn makes the expectation of excitement become a routine point of sadness. I don’t know how much my mom paid for that Griffey card — or even all of the magical, motherly strings she had to pull to get it — but when she gave it to me it came in a glass case, nearly twice the size of the card, which was inside a black-felt card holder, three times the size of the original card. I remember getting this and actually feeling happiness, euphoria, glee. With all of the other cards, I’d check my Beckett routinely like a young stockbroker, to see how prices had changed with all of my cards of actual value. With the Griffey, it didn’t matter. It was more than a card — it was my teddy bear, my doll, my version of Linus’s blanket. Over the years, there have been moments when just looking at it has been triggering — positively — in the way few things ever have. I know my mother, like many parents of the time, hoped that investing in the card would provide joy but also pay their children’s way through college. But we now know that Upper Deck made a million of them. The realized ubiquity of the card would have changed my opinion of its value if it were anyone else, but this was Junior Griffey. The Kid. My guy. And not only was he the greatest athlete of his time, the most important athlete of my life, but he was also the un-locker of memories I thought were lost.