Last night’s split-screen image, of front-runner Donald Trump in his own venue and the non-Trump Republicans clustered together elsewhere, is the starkest representation yet of a party that is cleft in two. But there is something puzzling and ethereal about this schism. The opposing factions are not divided over a policy question, like pro– and anti–Vietnam War Democrats in 1968, or pro- and anti-slavery Whigs in the 1850s. Nor do they disagree on general ideology, as happened when conservative Republicans seized the party in 1964 from mainstream ones. The dispute between Trump and his antagonists does not center any disagreement so major or direct. It is a conflict between the party’s political methodology and its governing program.

For all its increasing viciousness, it is difficult to identify specific issues at stake between Trump and Republican regulars. After some initial noises about raising taxes on the rich, Trump unveiled a highly regressive tax cut similar in its contours to those of his fellow Republicans. He is anti-abortion, hawkish, proposes to repeal Obamacare, opposed to any restrictions of greenhouse-gas emissions, and otherwise in line with party doctrine. Trump’s main policy differentiator is immigration, and here he differs from his opponents only in tone and emphasis. Establishment Republicans are currently attacking Trump on immigration from the right, not the left, obscuring any philosophical divide beyond all recognition.

At the same time, Trump is offering something genuinely transformational. His candidacy would reshape the Republican Party as more of a European-style white-identity party, rather than a party rooted in opposition to big government. Far-right parties in Europe organize their politics around opposition to immigration and defense of cultural traditionalism. Unlike the Republican Party, they do not take notably right-wing positions on taxes and spending. Indeed, they fuse together social traditionalism with populist economics in a political style some call herrenvolk democracy — a welfare state whose benefits should be restricted to people like us.

What makes the distinction difficult to identify is that Republicans have been using versions of this nationalist appeal for decades. Richard Nixon’s “silent majority,” Ronald Reagan’s disdain for “welfare queens,” both presidents Bush depicting their opponents as elitist fops — these are all iterations of white identity politics. The second President Bush took the racial edge off his appeal without losing the cultural thrust.

That is why, for all the conservative fury directed at Trump, the specifics of the case against him is oddly thin. National Review’s editorial denouncing Trump doesn’t call him an advocate of white identity politics, it calls him a “philosophically unmoored political opportunist.” Of the 19 columns it compiles denouncing Trump, only one mentions his racial demagoguery, and that one casts the problem entirely as an electoral liability rather than a moral failing (“imagine the parade of negative ads the Democrats are already preparing for radio stations with mainly black audiences and for Spanish-language television”). Trump’s most recent antagonist, Megyn Kelly, is, as Isaac Chotiner astutely notes, a longtime purveyor of right-wing culture-war hysteria, tinged with appeals to white Christians who are losing their country to rampaging black people and the War on Christmas. If Kelly were a candidate, judged by the same standards as Trump, she would be considered the more vicious demagogue.

So if movement conservatives have so little objection to Trump’s racial appeals, what explains the intensity of their rage? The disagreement lies in his commitment. For Republicans, white identity politics is a political style. A Republican presidential candidate might run on Willie Horton and opposing same-sex marriage, but after being elected, he was expected to turn to reducing the top tax rate and deregulating business. Cultural appeal was the means, and economics the ends. What conservatives fear is that Trump might upend that delicate, unstated system by turning the means into the ends.

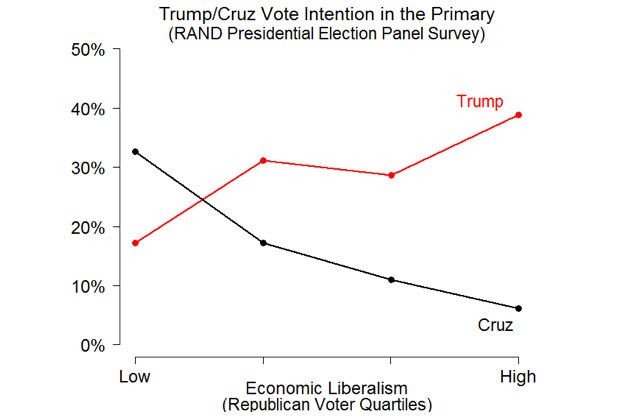

Their fear is by no means unfounded. Trump may currently line up with Republican doctrine, but he has not always. He has in the past praised single-payer health care, proposed higher taxes on the wealthy, and supported Democrats, casting justifiable suspicions on his true intentions. Those fears are compounded by worrisome gestures he makes toward economic populism. Trump has promised to save Social Security, to raise taxes on the rich, to let Medicare negotiate down the price of the prescription drugs it finances, and to replace Obamacare with “something terrific.” What’s more, Trump’s economic populism has reached a constituency within the party. The most economically liberal Republicans gravitate toward him:

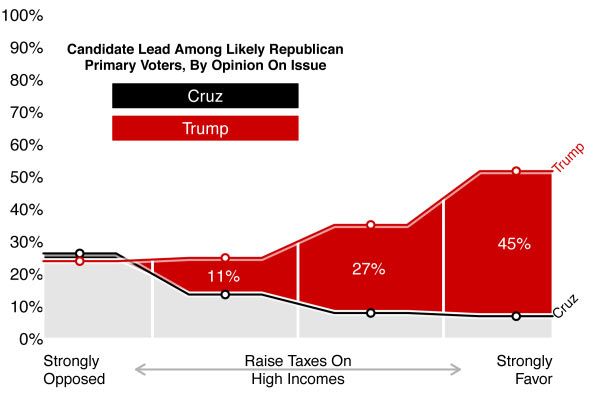

Relatedly, those Republicans most in favor of raising taxes on the rich also support Trump:

This constituency has always existed within the party. The traditional structure of Republican politics has marginalized its priorities, harvesting their votes at election time, and then implementing an agenda crafted by its business wing. Conservatives justifiably fear that Trump could upend this configuration — that he might use populism not just as an electoral strategy but as a governing blueprint.