There was once a time when any self-respecting Southern Baptist preacher had in his homiletic arsenal a blast at the Roman Catholic Church as the Book of Revelation’s Whore of Babylon, and its pontiff as Antichrist (a smear that went all the way back to Martin Luther). Southern Protestant anti-Catholicism flared up so intensely when Catholics Al Smith (1928) and John F. Kennedy (1960) ran for president that the region’s white-supremacy-based fidelity to the Democratic Party was ruptured. The hostility to Rome wasn’t merely theological; Catholic rejection (until fairly recently) of church-state separation raised fears the Vatican would dictate public policies to any American president. So argued the famous Evangelical minister Billy Graham and his close colleague in fighting Kennedy’s election, the Reverend Norman Vincent Peale, who as it happens was later Donald Trump’s pastor and spiritual mentor (both Graham and Peale later recanted their opposition to JFK).

This tradition of anti-Catholicism was especially evident in South Carolina. As recently as 2008 the old-school fundamentalist Bob Jones University in Greenville was a controversial speaking site for Republican presidential candidates due in part to an unrepudiated history of school leaders denouncing Catholicism (along with liberal Protestantism and all non-Christian faiths) as an anti-scriptural abomination.

Nowadays BJU is a bit of a relic alongside the proliferation of more modern conservative Evangelical universities like Liberty and Regents in Virginia. And while sin and heresy are still denounced weekly in thousands of Baptist pulpits in the Palmetto State, you could probably spend a month of Sundays in conservative Evangelical churches without hearing a whisper of anti-Catholicism. That is largely because of the emergence of a powerful alliance between conservative Evangelicals and traditionalist Catholics on culture-war issues like abortion and same-sex marriage, compounded by a common antipathy to mainline Protestantism and secularism. Where once the term “religious liberty” was strongly associated with Protestant opposition to putative Catholic tyranny, it’s now a cause uniting Christian conservatives across denominational lines against alleged government efforts to force compliance with laws banning discrimination and requiring contraceptive services.

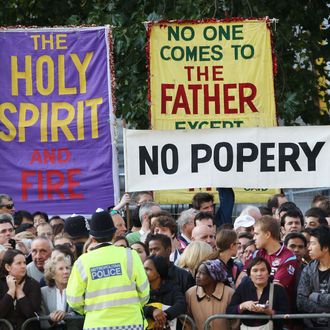

And so: Pope Francis’s suggestion that Donald Trump’s views on immigration might carry him beyond the bounds of Christianity is not likely to revive “No Popery” agitation or faint memories of once-widespread fears of papal interference in U.S. affairs in places like South Carolina. But precisely because the Protestant-Catholic détente in red-state America is a product of shared conservatism on public policy issues, Francis’s “heretical” stance on immigration could create a backlash that’s more political and cultural than religious.

To put it very bluntly, whatever else he purports to be (you know, the Vicar of Christ and all), Francis appears to your average South Carolina Protestant Republican as a Latin American leftist who’s trying to tell Americans how to deal with their own national security. Keep in mind that Republican orthodoxy now holds that border security isn’t just a matter of keeping Francis’s fellow Hispanics at bay, but also keeping out ISIS and other terrorists. So odds are high they will take umbrage at Francis’s “intervention” into U.S. politics, and share Trump’s annoyance at being told he’s beyond the religious pale. The more attentive conservatives received an early tutelage in rejecting Francis’s advice before and during his trip to the U.S. last fall, when his remarks about capitalism, climate change, and immigration were roundly rejected by Republican elected officials, including Catholics like Jeb Bush and Marco Rubio. Unsurprisingly, Bush and Rubio quickly came to Trump’s defense when Francis dissed the fiery mogul this week.

It’s just a fact of life in the U.S. today that the political expressions of religious people are often dictated more by politics and culture than by theology. If Francis had questioned Hillary Clinton’s or Barack Obama’s Christian faith, he would have been cheered from Fairfax to El Paso by the heirs of those conservative Evangelical activists who once worried about Catholic interference with American traditions of church-state separation. In going after Trump, Francis is just another “politically correct” outsider who doesn’t get it.