The most important moment in Thursday night’s campaign came on the final question, when the three non-Trump candidates were all asked if they would support him as the nominee. They replied that they would, even though Rubio has made “NeverTrump” a slogan for his campaign. Rubio should have used the slogan “InconceivableTrump,” so that Inigo Montoya could correct him. (“You keep using that word. I do not think it means what you think it means.”)

The strength and weakness of Trump’s campaign is his ability to create a separate reality. In Trump’s world, there are no logical principles other than “Donald Trump is a winner,” no concrete facts that cannot be bent to suit the maximal principle. This is a limitation because anybody who refuses to enter Trump’s alternate reality — say, a person who is reasonably well-informed about public policy — finds it terrifying. But it is also a strength because, for those who choose to live in Trump’s world, literally nothing he says can reflect badly upon him, because if it was bad, Trump wouldn’t be doing it.

Moderator Megyn Kelly attempted to penetrate the internal logic of Trumpworld by showing clips of him contradicting himself flagrantly. Every previous debate has shown Trump violating the rules of logic. This one showed it as clearly as any. Those previous debates also failed to yield any decline in Trump’s polling. The same result is likely to follow. For the people nestled inside Trumpworld, “Trump loses” is an oxymoron.

More clearly than ever before, Ted Cruz and Marco Rubio positioned themselves distinctly to Trump’s ideological right, hammering him for having donated to Democrats, failing to embrace the maximalist interpretation of the Second Amendment, and being fond of compromise. Trump seemed happy to let himself occupy the center.

The roots of Rubio’s failure to disavow Trump — thus repudiating the entire basis for his claim that Trump is a sociopathic con man — could be seen in an earlier answer about Flint, Michigan. Rubio was asked, “Without getting into the political blame game here, where are the national Republicans’ plans on infrastructure and solving problems like this?” His answer has to be read in its entirety to be understood:

Well, I know I’ve talked about it, and others in our campaign have talked about it, and other candidates have talked about it, as well. What happened in Flint was a terrible thing. It was systemic breakdown at every level of government, at both the federal and partially the — both the state and partially at the federal level, as well.

And by the way, the politicizing of it I think is unfair, because I don’t think that someone woke up one morning and said, “Let’s figure out how to poison the water system to hurt someone.”

(APPLAUSE)

But accountability is important. I will say, I give the governor credit. He took responsibility for what happened. And he’s talked about people being held accountable …

(APPLAUSE)

… and the need for change, with Governor Snyder. But here’s the point. This should not be a partisan issue. The way the Democrats have tried to turn this into a partisan issue, that somehow Republicans woke up in the morning and decided, “Oh, it’s a good idea to poison some kids with lead.” It’s absurd. It’s outrageous. It isn’t true.

(APPLAUSE)

All of us are outraged by what happened. And we should work together to solve it. And there is a proper role for the government to play at the federal level, in helping local communities to respond to a catastrophe of this kind, not just to deal with the people that have been impacted by it, but to ensure that something like this never happens again.

Asked to avoid the blame game and offer specific solutions to urban-infrastructure problems, Rubio is unable. He conceives of the question entirely in partisan terms. He attacks the notion that Republicans consciously decided to poison children, thereby ruling out any possibility of government negligence as self-evidently preposterous. He has nothing resembling a specific idea on the issue, only the firm conviction that Republicans could not have done anything wrong.

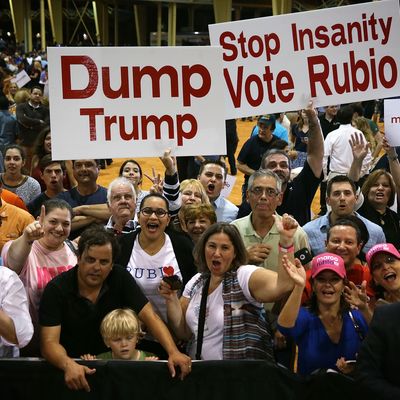

This belief system has been the strength of Rubio’s campaign. It is as open as Trump’s internal logic is closed — at least to anybody committed to the party. Rubio has run as the pan-Republican candidate, identifying the consensus position on every issue and locating himself there. That stance has made him widely acceptable. And it is the logic he instinctively fell back on in his final answer, when he was asked very simply if he meant what he said about Trump. Rubio did not mean it — Rubio would never turn against the party.