Donald Trump represents a threat to conservatism in two ways. He is extremely likely to lose if nominated, and even if elected, he engenders little confidence that he will see the party agenda through. The fact that Trump threatens rather than promotes conservative interests has enabled conservative intellectuals to see certain truths that they once obscured: There are deep strands of racial resentment and anti-intellectualism running through the Republican electorate. But these angry spasms of half-recognition attempt to quarantine Trump from a political tradition of which he is very much a part. Bret Stephens’s column in today’s Wall Street Journal provides a comic example of the sort of naïveté circulating among the anti-Trump right. William F. Buckley’s break with the anti-Semitic right, argues Stephens, established the conservative movement as racism-free. “The word for Buckley’s act is ‘lustration,’ and for two generations it upheld the honor of the mainstream conservative movement. Liberals may have been fond of claiming that Republicans were all closet bigots and that tax cuts were a form of racial prejudice, but the accusation rang hollow because the evidence for it was so tendentious.” Now, Stephens laments, that sterling record of racial innocence is threatened by Trump.

It is true that Buckley disassociated conservatives from one strand of the far right. On the whole, though, Buckley set the conservative movement and the Republican Party on the course it finds itself today. Buckley was a defender of white supremacy and segregation in the 1960s, and then a defender of apartheid in the 1980s. Buckley’s publisher, William Rusher, argued for the GOP to recast itself as an ideologically conservative party by bringing southern whites into the fold. Buckley helped turn a party that once had congenial relations with academic experts into a raging populist force. “I would rather be governed by the first 2000 people in the Manhattan phone book,” he famously declared, “than the entire faculty of Harvard.”

If you comb through Buckley’s writings on race, the emphasis falls less on a principled defense of racial apartheid in the United States and South Africa (though he did offer that) than on resentment against its critics. Buckley was simply far less interested in racial oppression than in the hypocrisy, obnoxiousness, and potential overreach of its critics. That spirit defined racial conservatism then, and defines it today. To read the pages of National Review, or The Wall Street Journal editorial page, racism against nonwhites is a virtually nonexistent problem. Conservatives are instead fixated on the way the racial debate has been turned against conservatives or white people.

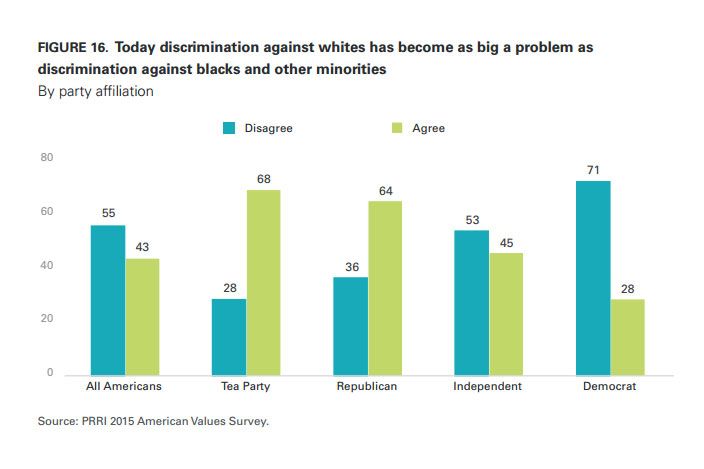

Now, for those unfamiliar with my beliefs on this subject, I think it is absolutely correct that the left has adopted dogmatic and unfair ways of conceptualizing identity politics so as to stigmatize any dissent from its preferred solutions. But one can and must believe this while also understanding that racism remains a demonstrably powerful force in American life. No such recognition exists in conservative discourse. In National Review and The Wall Street Journal, race is just a card. Republican voters heavily believe that whites have become, on balance, the victims of racial discrimination:

As for Trump’s anti-intellectualism, he is certainly less cogent than figures like Marco Rubio or Ted Cruz. But he has no weaker a command of the issues than Sarah Palin, who blathered incoherently through the closing months of the 2008 campaign. At the time, Palin, a reliable conservative, enjoyed blanket support of the movement, including National Review and Bret Stephens. Even a year after the 2008 election, long after Palin’s lack of basic familiarity with American government had revealed itself, conservatives continued to defend her.

In 2009, Rich Lowry, a successor to Buckley as National Review editor, admiringly assessed her populist appeal to the party base. Palin, he wrote:

represents less a philosophical strain on the right than an affect and a demographic. What makes her otherwise orthodox conservatism different is the plain-spoken, combative way she expresses it and the constituency she attracts…

Republicans need these voters more than ever given the roiling grassroots revolt against Obama’s governance. Without them, they can’t get a majority; they’d be doomed if they were ever to slide into a splinter party.

The Trump constituency factored into conservative calculations all along. Conservatives courted them, defended them, and understood all along that their votes would supply the margin needed to implement conservative ideas, even if many of those ideas (like supply-side economics and neoconservative foreign policy) had little natural appeal to those voters. They even understood, as Lowry very explicitly laid out, that those voters would doom the orthodox conservatives if they formed a splinter party. The one thing Buckley and his successors failed to imagine, though, is that those people would actually one day take over.