In July 2009 Chris Jankowski sat down at his Richmond home with the morning New York Times. It had been eight months since Barack Obama defeated John McCain in the presidential election, capturing Republican stronghold after stronghold and helping to usher in a Democratic supermajority in the Senate. On television and on the front pages of newspapers, pundits had openly questioned how the GOP would survive to the next election. Even the brightest conservative thinkers thought the 2008 results signaled danger for the GOP.

That July morning, buried inside a story about state legislatures and census projections, Jankowski read something that made him think 2008 wasn’t so fateful after all: “2010 is not just any election year,” wrote Times correspondent Adam Nagourney, “it is crucial given that this class of governors will be in charge as their states draw Congressional and state legislative districts as part of the reapportionment process after the next census.” Jankowski immediately recognized the opportunity. As written in the Constitution, every state redraws all of its lines every ten years. That means elections in “zero years” matter more than others. Jankowski realized it would be possible to target states where the legislature is in charge of redistricting, flip as many chambers as possible, take control of the process, and redraw the lines. Boom. Just like that — if Republicans could pull it off — the GOP would go from demographically challenged to the catbird seat for a decade. At least.

“I read it and I thought we could do this,” Jankowski told me. As one of the leading tacticians behind the Republican State Leadership Committee, Jankowski had spent years trying to arm-twist GOP strategists and donors to spend more on down-ballot races: state houses, state attorneys general, local judges. Those might not be the sexy elections to invest in, but donations that would be a mere drop in the bucket to a presidential or Senate candidate might make all the difference at the local level. And unlike gridlocked Washington, D.C., policy outcomes could actually be influenced in state capitals.

Every state handles creating their district maps a little differently. Arizona, Iowa, California, Washington, Idaho, and New Jersey all use various commission models. But the vast majority of states leave redistricting up to some combination of the legislature and the governor. Jankowski looked for states that were likely to gain or lose seats after reapportionment, and would therefore be tearing up the old maps and starting from scratch with a different number of districts. Pennsylvania, Michigan, Texas, and North Carolina made that list. He looked for states where control was tight, and swinging just a handful of districts might tip the chamber to the Republicans, such as Wisconsin, Ohio, and Virginia, even New York. Then he checked for states where Republicans might control the legislature and the governor’s office, and would therefore be able to lock the Democrats out of redistricting altogether. He didn’t want a Democratic governor, for example, to be able to veto a plan.

The annual report by Jankowski’s organization, the Republican State Leadership Committee, laid out the mission for the world to see: “Drawing new district lines in states with the most redistricting activity presented the opportunity to solidify conservative policymaking at the state level and maintain a Republican stronghold in the U.S. House of Representatives for the next decade.”

“Our pitch document said, look, there are 25 true swing congressional districts,” Jankowski told me as we sat in the conference room of his Richmond offices. “We went back to those races from 2002 to 2008, and we found that $115 million had been spent on those 25 congressional races. All hard dollars. We had a graphic on the screen: 115 million hard dollars or $20 million in soft and we can fix it. We can take control of these 25 districts. We can take them off the table.” They called their project REDMAP.

Jankowski’s foresight wasn’t the only factor in the GOP’s ensuing control of Congress. The party was also able to take advantage of massive new amounts of public data drawn from social media that allowed them to pinpoint likely voters with more accuracy than ever before, and advances in mapping technology that made it possible to redraw districts precisely around the location of those voters.

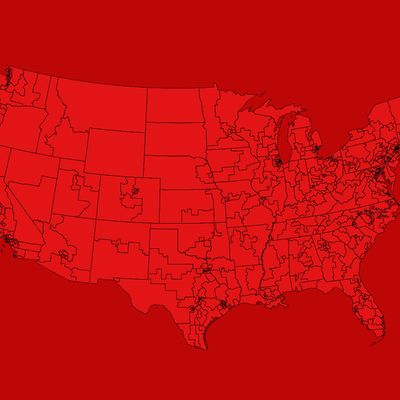

The result: The gerrymander of 2011 built such a firewall around GOP control of the House that when Barack Obama was reelected in 2012, Democratic congressional candidates earned 1.4 million more votes than Republicans, but the GOP retained a 234-201 majority. You might even argue it worked too well, creating the solid conservative districts that gave rise to the renegade House Freedom Caucus, forced Speaker John Boehner out of office, and fomented the grass-roots anger that fueled Donald Trump’s ascent and punctured the GOP establishment.

However, even in this most unpredictable campaign, and even with polls showing that likely Democratic nominee Hillary Clinton would rout either Trump or Ted Cruz by double digits, the GOP’s gerrymandered fortress around the House stands strong. In April, Larry Sabato’s widely respected Crystal Ball Report pushed the Electoral College toward the Democrats and predicted the party might also take six seats in the U.S. Senate. In the House? Sabato’s essential guide sees just a five-to-ten-seat gain for the Democrats. They see 227 seats in the GOP column, 188 safe/likely/leaning Democratic, and 20 toss-ups. “Split the toss-ups and Democrats net ten seats, or only a third of what they need,” David Wasserman of Cook Political Report, perhaps the preeminent House watcher, concurs. He calls only 31 Republican seats “at risk.” That means “Democrats would need to win an impossibly high 97 percent of them — and hold all their own seats — to take back control.” In all likelihood, President Hillary Clinton will face the same intransigent House as Barack Obama, and likewise, her policy agenda will be dead on arrival from day one.

The GOP’s dominance of Congress has mostly been interpreted in terms of the increased partisanship that’s been driving American politics for the last two decades — the Republican Party has moved much further right, the Democrats have moved a little further left, bipartisanship is dead, and Americans are more and more likely to stay loyal to one party and live near like-minded individuals. The most influential book shaping this discussion remains Bill Bishop’s often brilliant and always provocative The Big Sort: Why the Clustering of Like-Minded America is Tearing Us Apart, which redrew the way the smart set thought about redistricting. Bishop argued that we’d sorted ourselves into increasingly homogenous and “ideologically inbred” communities. Our polarized politics and congressional districts were not the fault of gerrymandering, he argued, but the result of a new American propensity to cluster around people who shared our opinions on politics and religion, our taste for Girls or Two Broke Girls, Whole Foods or Hobby Lobby. Bishop’s right: We have surrounded ourselves with people who agree with us.

But the extent of the REDMAP effort was something new to American politics, and The Big Sort can no longer be the only aperture through which we see our uncompetitive congressional races. We may well have sorted ourselves into cities, suburbs, or rural America. But 435 sets of lines, drawn by experts, informed by more data than ever before, have sorted us into congressional districts. Those districts, intended by the Founders to be directly responsive to the peoples’ will, have now been insulated from it. The Big Sort obscures the national debate over just how effective the GOP strategy has been. “Everybody assumes that it’s sorting, the big sort, and that demographics are driving this,” said Chuck Todd, the host of NBC’s Sunday morning tradition Meet the Press and a district-by-district student of American politics. “But the fact of the matter is they’re not looking at the lines.”

In politics, a “ratfuck” is a dirty deed done dirt cheap. In All the President’s Men, Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein quoted Donald Segretti, an operative tied to Nixon’s reelection campaign, as using the colorful term to describe political sabotage and the early shenanigans of strategists tied to the Watergate burglars. Twenty years later, the phrase emerged again when the new Republican National Committee legal counsel working with Lee Atwater would be tasked with fixing the Republicans’ redistricting problem. Their solution: Use the Voting Rights Act’s provisions governing majority/minority districts to create African-American seats in southern states. Work closely with minority groups to encourage candidates to run. Then pack as many Democratic voters inside the lines as possible, bleaching the surrounding districts whiter and more Republican. It re-segregated congressional representation while increasing the number of African-Americans in Congress. The strategy became known as the “unholy alliance” because it benefited black leaders at the expense of the Democratic Party. Ginsberg had another name for it when asked to describe it for a reporter: “Project Ratfuck.”

The REDMAP ratfuck, however, was done in such plain sight that Karl Rove himself announced it on the op-ed page of The Wall Street Journal. “Some of the most important contests this fall will be way down the ballot in communities like Portsmouth, Ohio and West Lafayette, Ind., and neighborhoods like Brushy Creek in Round Rock, Texas, and Murrysville Township in Westmoreland County, Pa.,” Rove wrote in early March 2010 — naming some of the specific towns where Republicans would come gunning for Democratic incumbents. By that time, Jankowski and his boss Ed Gillespie had repositioned the RSLC as a redistricting vehicle.

During early 2010, Gillespie and Jankowski took a PowerPoint presentation on the road — they met with Wall Street donors, oil magnates, hedge-funders, Washington lobbyists, and trade associations, anyone open to an audacious, long-term play. “A lot of what we were selling internally to donors in a non-public way was stewardship,” he said. By the end of 2010, their fund-raising haul would make them the fourth wealthiest 527 in Washington, behind only their allies at the Republican Governors Association ($117 million), the Democratic Governors Association (a distant second with $55 million), and AFSCME ($49 million).

Meanwhile, by the summer of 2010, polls had gone from bad to worse for Barack Obama and his party. Almost every Democrat looked vulnerable. “Everyone’s house was kind of on fire that summer with death panels and things like that,” Carolyn Fiddler of the Democratic Legislative Campaign Committee told me. “After 2008 and all those successes, it was such a jarring shift that everyone went into reactive mode.” If the Democrats had any redistricting play of their own, it got buried by discouraged Democratic voters and by fired-up Republicans.

Suddenly, the states that looked like long shots and fantasies when Jankowski first white-boarded REDMAP were all in play. Upwards of $18 million arrived after Labor Day and got redirected to races in Ohio, Michigan, North Carolina, Wisconsin, Pennsylvania, Indiana, and other states — that’s an avalanche of campaign cash in state legislative races where a candidate’s entire budget might be less than six figures. Jankowski began expanding his playbook. In Ohio, they started out targeting 10 to 12 House districts, spent in all of them, then realized the most essential five, and doubled down on cable TV and more mail. In Pennsylvania, they eyed 20 of 203 districts, and kept polling for the issue that would work to defeat opponents. When November came, the Republicans swept to modern record gains in the midterm election. The GOP captured 63 seats in the House of Representatives, the biggest midterm swing since 1938, and on the state level, Republicans grabbed 680 new seats. President Obama, recognizing the historic nature of the defeat, stood before the nation the following day, chastened and newly chained to John Boehner and Mitch McConnell as his partners, and declared it a “shellacking.”

After November, the RSLC moved quickly to consolidate its gains, sending a letter to state legislative officials and other redistricting players offering their expertise on redistricting efforts: “Our team would be happy to assist in drawing proposed maps, interpreting data, or providing advice,” they wrote. “Our team can also provide strategic advice in cases of litigation as well.” Once newly elected legislatures with Republican majorities were in power in Florida, Wisconsin, North Carolina, Ohio, Michigan, and several other states where Republicans controlled every aspect of redistricting, the political sleight of hand began. In Wisconsin, legislative aides barricaded themselves in law offices to work on maps and forced legislators who wanted to see the new maps to first sign nondisclosure agreements. In Florida, where a constitutional amendment had just passed mandating the removal of partisan politics from redistricting, elected officials held public hearings largely as a ruse while operatives drew the real maps behind the scenes.

In Ohio, they holed up in a secret hotel suite nicknamed “The Bunker,” where some of Ohio’s smartest political strategists drew up the new maps, in active consultation with national Republicans in Washington, D.C., and top political aides to then–House Speaker John Boehner. Their secrets might have stayed completely private had a handful of revealing emails not been discovered under a public-records request from the Ohio Campaign for Accountable Redistricting. Those emails are enough to show exactly how the Buckeye State was ratfucked.

The process started that spring, behind closed doors and away from the state capitol, but perhaps the most telling email is from the evening of September 12, 2011. The next morning, Ohio legislators would be introducing a bill laying out the state’s new congressional map. Two veteran Republican political hands, Heather Mann and Ray DiRossi, had been focused on the new lines for many months. The bill had to be finalized and distributed to officials right away — but first, Tom Whatman of Team Boehner, the commander of the House Speaker’s political machine — emailed Mann, DiRossi, and a redistricting coordinator at the National Republican Campaign Committee with a last-second special request.

“Guys: really really sorry to ask but can we do a small carve out down 77 in Canton and put Timken hq in the 16th. I should have thought about this earlier,” he wrote at 9:28 p.m.

“Yeah, sure, no problem,” replied the NRCC’s Adam Kincaid just eight minutes later. His email signature identifies him as the NRCC’s Redistricting Coordinator. “Ray/Heather, do you want me to do it and send the file over, or will y’all do it?”

“You do and get equivalence file to use asap,” answered DiRossi, just moments later.

“Thanks guys,” Whatman wrote back at 9:41 p.m. “Very important to someone important to us all. I relly (sic) should have thought of this.”

By 10:55 p.m., Kincaid circulated the new maps, as he wrote, “virtually unchanged from before.” The “someone important to us all” is easy to decode. That’s the House speaker himself, who launched Team Boehner in 2011 focused on “one goal: maintaining and expanding our new House majority.” Boehner tapped Whatman, a veteran Ohio GOP operative, to lead those efforts, which naturally included a close eye on redistricting.

And by “virtually unchanged,” Kincaid meant that he’d added a peculiar peninsula jutting out of the northeast corner of Republican incumbent Jim Renacci’s new district. It’s the only part of Canton, Ohio, sitting in the 16th district, and not the 7th. The census shows that the population of this puppet-shaped peninsula is zero. It contains something more valuable than even voters: campaign contributions. The lines were hastily redrawn for the purpose of adding the Timken Company and two of its industrial manufacturing plants to the 16th. Perhaps coincidentally, Renacci was the recipient of almost $210,000 in political donations from Timken executives, family members, and the company’s foundation over the previous three years, according to the Cleveland Plain-Dealer.

The speaker of the U.S. House and his political team don’t actually have an official role to play in Ohio redistricting. By law, Ohio’s congressional districts are drawn by the state legislature, with veto power to the governor. They didn’t need an official role: Republicans controlled the entire process, from a 4-1 majority on the Apportionment Board to domination of the legislature and governor’s office. They held those advantages because of REDMAP. In 2008, Barack Obama had helped Democrats, in fact, capture a decisive 53-46 majority in the state House. To turn that around, REDMAP spent a massive $1 million on a mere six state House races in 2010. They won five of six, and Republicans rode the anti-Obama wave all the way to an even more decisive 59-40 cushion. The GOP added two seats to their majority in the state Senate, grabbing a 23-10 advantage.

That’s the rhythm of a swing state, after all, and how Ohio politics has traditionally worked. A statewide swing toward the Democrats elects Democrats to the legislature. A big year for Republicans nationally puts the GOP in charge. What happened in 2012, however, broke all the usual rules. It was a solid victory by Barack Obama that nevertheless continued the Republican dominance of the state legislature and the congressional delegation. The district lines Whatman, Mann, and DiRossi created provided sandbags for a Democratic wave.

In 2012, Obama defeated Mitt Romney by three percentage points in Ohio. U.S. senator Sherrod Brown, one of the most liberal members of the Senate, was reelected by six points and a 325,000-vote margin over the Republican state treasurer. Democrats got more votes than Republicans in races for the state House — but Republicans commanded a 60-39 seat supermajority, despite getting less support at the ballot box. The aggregate statewide vote for U.S. House races did narrowly favor Republicans — but that slim edge earned them a staggering 75 percent of the seats. The GOP retained the U.S. House with a 234-201 margin. Had 17 more seats changed hands, so would have the House. Now you know why John Boehner’s political team was so interested in redistricting: The eight-seat Ohio advantage provided 25 percent of his cushion.

The strategy was repeated in every state the Republicans won. In Pennsylvania there are almost 1.1 million more registered Democrats than Republicans. In the 2008 Obama wave, Democrats took a 12-7 advantage. Republicans reversed it to 12-7 in the 2010 GOP wave — and then they locked in such advantageous new lines that their majority grew to 13-5 in 2012 — even as President Obama crushed Mitt Romney by some 310,000 votes, and despite 2.7 million votes for Democratic House candidates compared to only 2.6 million for Republican nominees. Democratic House candidates won 51 percent of the vote and only 28 percent of the seats.

The debate over how you draw lines can feel a little theoretical until you see exactly how it is done these days. Mapmakers have access not only to the massive amount of demographic data collected by the U.S. census, but they can also purchase any number of other databases or public records. Anything you like on Facebook, anything you purchase on Amazon, any license or registration or magazine subscription — in the same strange way that an ad might track you across the web, it’s likely landing in some direct marketer’s database as well.

William Desmond works as a senior microtargeting analyst for a company called Strategic Telemetry, and served as the lead map-drawing consultant to the Arizona Independent Redistricting Commission on their legislative and congressional districts. He joined the firm after being one of the young stats wunderkinds who, as the project manager for modeling on the 2008 Obama for America campaign, helped elect Barack Obama. There’s Obama inauguration memorabilia on the walls; Strategic Telemetry was viewed as a center-left firm when the Arizona commission hired them, and suspicious conservatives used the firm’s political history to try and discredit the independence of the commission.

When I visited him at his home in Scottsdale, he walks me through Maptitude, the desktop program he used to build district lines. He still has the laptop he did all the mapping on, but stopped using it because of all the legal challenges to the Arizona map. It’s been forensically examined at least twice, and lawyers have perfect copies — but just to be safe, he doesn’t want to show me how to draw maps only to later find them entered into evidence in court. That’s how contentious the post-2010 census became in Arizona.

Maptitude might be the best political video game ever. It starts simply enough. Open plan manager. Select the type of map you want to build. We select an Arizona legislative grid. You choose the number of districts, and the map divides that by the state’s population to give us the exact number of people we’ll need in each one to pass constitutional muster. Maptitude comes preloaded with all the census data you could ever imagine, and some that you had no idea was even collected. A census block is the most granular level and corresponds to a city block. Put census blocks together to form census tracts, then cities and counties.

Within each census block, the statistics get even more granular: total population, male population, female population, white population, multi-race, mixed race, “every other race,” he says, scrolling past hundreds of different backgrounds and ethnicities. As you highlight a census block for your district, it can give you a running tally of every imaginable breakdown. And the more information you add — political, economic, demographic — the more exact a picture you have, street by street. Make a change, move a line in any direction, and you can see what it does to all of the neighboring districts.

“That’s how you start weighing in different things,” he says. “When we actually did this for the commission, we added a ton of other data to those kind of background files — things like election results going back through the last decade, some population estimates, prisoner populations, other things that the commission deemed important to consider when trying to draw the maps.”

Layer on election results and you can almost immediately understand how these districts will perform for either party, in a good year or in a bad year. This level of technological sophistication, combined with hardened partisanship among voters who define themselves as red and blue, makes our voting preferences almost shamefully easy to predict. Add census information and public records to the formula — say, household income, ethnicity, and the elections you’ve voted in — and the picture becomes even clearer. The data and the technology make tilting a district map almost as easy as one-click ordering on Amazon.

In 2012, Barack Obama won reelection, besting Mitt Romney in the Electoral College by a decisive 332-206 margin, and by some 3.5 million in the popular vote. One-third of the Senate was up, and Democrats handily won 23 of the 33 races. Nationwide, 1.4 million more Americans cast their votes for Democratic U.S. House candidates than Republican candidates — and yet Republicans still held a 33-seat advantage in the House. This was the first time since 1972 — when Democrats withstood Richard Nixon’s 49-state sweep of George McGovern and held the House — that the party with the most votes did not also win the most seats. REDMAP built an effective, enduring firewall — a firewall against popular will. And it held strong.

But there have been unintended consequences: Last fall, when John Boehner resigned as House Speaker, it was in no small part due to a political environment enshrined by the new electoral maps, which Boehner’s own political team helped create. His job was made impossible by a new breed of post-2010 congressional Republicans — pure in their conservatism, united in their distaste of deal-making with Democrats and President Obama, and certain that they represented districts where their only electoral challenge was by someone even further to their right. Boehner’s top deputy, Eric Cantor, once a conservative young Turk himself, also lost his seat, in a summer 2014 primary challenge to an even more hardline Republican backed by the influential talk-radio power Laura Ingraham.

By all but eliminating competitive general elections, redistricting had made the Republican Party too conservative even for what had been the most conservative, revolutionary edge and given rise to the ultra-conservative agenda playing out in the 2016 Republican primary. By creating safer and safer seats, held by more and more conservative members, Republican strategists generated deeper and deeper frustration among the conservative base when congressional majorities did not lead to exactly the policies they hoped to see. Hence, Donald Trump and Ted Cruz surged while establishment candidates including Jeb Bush, Chris Christie, and even Ohio governor John Kasich failed to gain traction amongst a GOP base that had moved even further to the right of them. “Big Data has ruined American politics. Big Data could be used for good and is instead used for evil. Big Data has given you the tools to not have to coalition-build,” Todd tells me. “There is no persuasion. We don’t do political persuasion anymore. If you have competitive districts, you force political persuasion. The data is what has destroyed our political campaigns.”

After their sweeping wins in 2012, Jankowski predicted that the new Republican maps would take decades to undo. He’s likely right, though there are some efforts to push back against the REDMAP gains. Last fall, Ohio passed a referendum that could take some of the partisanship out of redistricting. An interesting lawsuit out of Wisconsin attempts to swing Justice Anthony Kennedy with a theorem to show when gerrymandering has gone too far. Barack Obama called for nonpartisan redistricting reform in his final State of the Union (of course, so did Ronald Reagan in one of his last interviews as president). Democrats, caught unprepared in 2010, have vowed to raise tens of millions on down-ballot races heading into the 2020 census-year elections.

But if Democrats tried a BLUEMAP, they’d have to win in 2020 on these GOP-drawn maps. There also would be no element of surprise. Republicans designed this play and will be ready for the Democrats to try one of their own. Moreover, if Hillary wins in 2016, the party in control of the White House typically loses seats in the midterm, meaning Democrats could lose seats in 2018 and need a record landslide in 2020. “We’re not going to be outspent,” Jankowski tells me, and then explains why it almost won’t matter what the Democrats do to try and untilt the table. “In a great year, they will get a seat at the table that will be helpful to them. It will take further Democratic trends in the next decade to make that seat at the table result in real congressional gains that stabilize this thing back to ‘fairness.’” Sometime during the 2020s, he suggests, the demographic shift that Democrats always claim is around the corner might actually arrive. “I think it would be an oversell beyond that,” he says. “If the Republican Party continues to underperform, we will be a minority party regardless of redistricting.” By then, though, it’ll be 2031.

Adapted from Ratf**ked: The True Story Behind the Secret Plan to Steal America’s Democracy by David Daley, to be published June 2016 by Liveright.