Donald Trump would probably be the worst candidate any major party has ever nominated — grossly uninformed, disorganized, personally and ideologically repellent to a majority of the public, and so unreliably attached to its core agenda he could potentially blow the party apart. Ted Cruz would be a much better choice. But there is a huge gap between “much better” and “good.” Cruz would not be a good nominee. He’d be very, very bad.

As the electorate has hardened into polarized camps, with the Democratic camp growing slowly every four years through cohort replacement, Republicans face a strategic challenge to broaden their appeal to the presidential electorate. Several potential strategies have emerged. They can try a targeted appeal to Latino and Asian-American voters by embracing immigration reform; they can soften their stance on gay rights and other social issues; they can move to the center on economics by redirecting their attention from reducing taxes on the rich to problems faced by the working class; or they could simply find a likable pitchman to make their old policies appear less threatening.

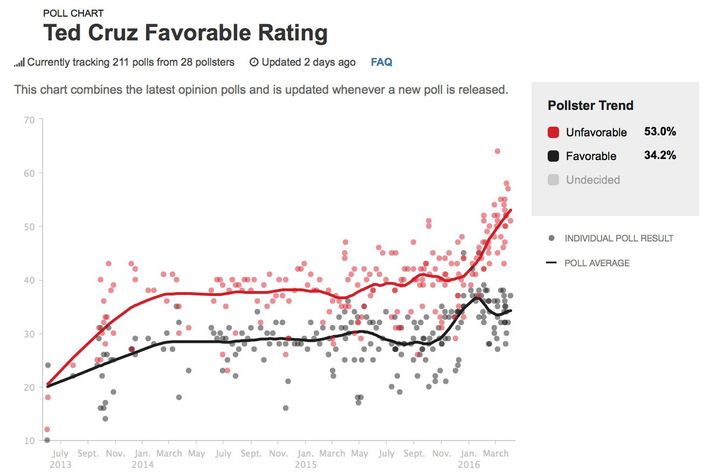

Cruz has closed off all of these strategies. He is weighted down by all of the liabilities that any standard Republican candidate would bring to the general election. He advocates for a huge tax cut for the rich and deregulation of Wall Street, and would eliminate the Clean Power Plan and take away health insurance from some 20 million people who’ve gained it through Obamacare. He has defined himself as more militant and uncompromising than any other Republican in Congress, and many of his fellow Republican officeholders have depicted him as a madman. This is a broad heuristic — Ted Cruz is the candidate whose main reservation with the Republican Party is that it’s too thoughtful and compromising. This definition colors Cruz’s public image and accounts for high unfavorable ratings despite a relatively brief time on the public stage.

That overarching image does not include the details of Cruz’s policy ideas, which would be litigated in the general election if he captures the nomination. But here is where the story gets even worse. The close-up picture of Cruz is even more disturbing than the broad strokes. He has taken a number of specific stances that make him far more vulnerable than a generic Republican candidate.

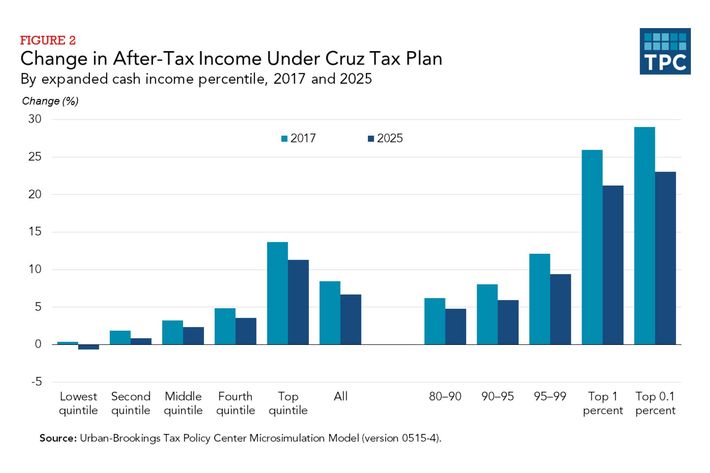

Begin with taxes. In addition to the de rigueur ginormous tax cut for rich people, Cruz proposes a massive shift of the tax burden away from income taxes to sales taxes. So, not only would Cruz’s plan give nearly half of its benefit to the highest-earning one percent of taxpayers (who would save, on average, nearly half a million dollars a year in taxes per household), but it would actually raise taxes on the lowest-earning fifth:

That tiny blue bar on the far left depicts the higher tax burden Cruz would impose on the lowest quintile. But the aggregate figure does not quite capture the political explosiveness of the plan. As Matthew Yglesias notes, Cruz’s sales tax would inflict special hardship on the elderly, who earn very little and spend (on the whole) more than 100 percent of their annual income. It is a longtime conservative dream to shift the tax burden from income to consumption, but one reason the Republican Party has shied away from such a plan is that the transition would impose huge costs on the generation that grew up paying income taxes and then would suffer from the transition to consumption taxes. Cruz’s plan would leave him vulnerable to devastating attacks.

Cruz has taken other stances from which other Republicans with national ambitions have shied away. He proposes to eliminate, among other agencies, the Department of Education, a cause most Republicans abandoned two decades ago as a hopeless political albatross. He’s committed to a legal and political rollback of legalized same-sex marriage, and has embraced a pastor who has endorsed the death penalty for homosexuality. He opposes all abortion, without exceptions for rape or incest. Republicans are justifiably reluctant to defend a vision of America where happily married same-sex couples have their unions involuntarily annulled and women are forced to spend nine months carrying their rapist’s child to term.

Elections are not policy seminars, but the vulnerabilities in Cruz’s platform are not subtle or difficult to communicate. Cruz’s career is dedicated to ignoring any pragmatic recognition of the limits to Republican power or the appeal of conservative orthodoxy. Were it not for the rise of Donald Trump, the Republican Establishment and even most conservatives would be frantically working to prevent his nomination. Only Trump’s astonishing success has made the once-unfathomable prospect of a Cruz nomination seem comparatively normal.