The liberal case against Hillary Clinton rests in large part upon her associations — people she surrounds herself with and whose judgment she relies upon. She has caught an enormous amount of flak, some of it fair, for her ties to figures in the finance industry or advisers with morally questionable worldviews. By the same token, what should we make of Bernie Sanders’s decision to appoint Cornel West as one of his advisers to the Democratic Party’s platform committee?

West, of course, has socialist views largely in line with Sanders’s own. But West also has a particular critique of the sitting Democratic president that goes well beyond Sanders’s expressions of disappointment. West’s position is not merely that Obama has not gone far enough, but that he has made life worse for African-Americans:

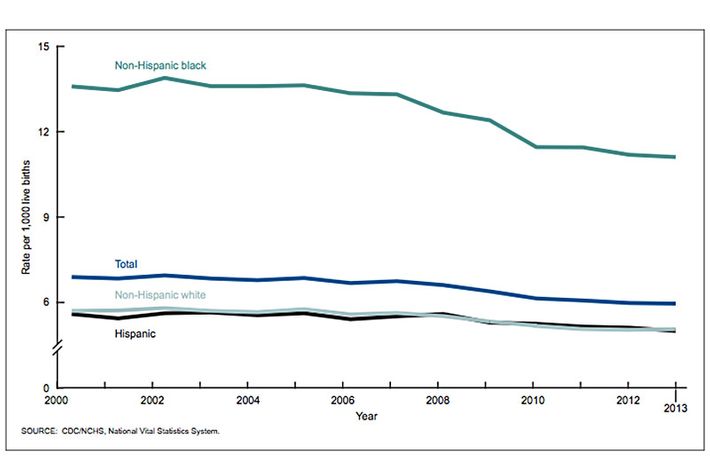

>On the empirical or lived level of Black experience, Black people have suffered more in this age than in the recent past. Empirical indices of infant mortality rates, mass incarceration rates, mass unemployment and dramatic declines in household wealth reveal this sad reality. How do we account for this irony? It goes far beyond the individual figure of President Obama himself, though he is complicit; he is a symptom, not a primary cause. Although he is a symbol for some of either a postracial condition or incredible Black progress, his presidency conceals the escalating levels of social misery in poor and Black America.

The African-American unemployment rate has fallen to its lowest level since 2008. The African-American uninsured rate has fallen by more than half, and the administration has undertaken a wide range of liberalizing reforms to the criminal-justice system. The notion that Obama has made life worse for African-Americans rests entirely on affixing the blame for the 2008 economic collapse on him, without giving him any credit for the wide-ranging measures to alleviate it, or the recovery that has ensued. This is, in other words, the Republican Party’s method of measuring Obama’s record, and it’s the sort of grossly unfair cherry-picking that no good faith critic would use.

West does not merely lament the alleged worsening of conditions for African-Americans that he claims Obama has caused. He has a theory for it:

“I think my dear brother Barack Obama has a certain fear of free black men,” West says. “It’s understandable. As a young brother who grows up in a white context, brilliant African father, he’s always had to fear being a white man with black skin. All he has known culturally is white. He is just as human as I am, but that is his cultural formation. When he meets an independent black brother, it is frightening. And that’s true for a white brother. When you get a white brother who meets a free, independent black man, they got to be mature to really embrace fully what the brother is saying to them. It’s a tension, given the history. It can be overcome. Obama, coming out of Kansas influence, white, loving grandparents, coming out of Hawaii and Indonesia, when he meets these independent black folk who have a history of slavery, Jim Crow, Jane Crow and so on, he is very apprehensive. He has a certain rootlessness, a deracination. It is understandable.

“He feels most comfortable with upper middle-class white and Jewish men who consider themselves very smart, very savvy and very effective in getting what they want.”

West’s theory is essentially the mirror image of the notion, peddled by Dinesh D’Souza and Newt Gingrich, that Obama absorbed a racial ideology from one of his parents. For Obama’s unhinged right-wing critics, that parent is his father. For West, it is his mother. The racial biases he inherited allegedly define his worldview and turn him into a tool of racial bias — for black people, in the right-wing version, and against them, in West’s. Then you have West’s dismay at Obama’s excessive comfort with wealthy Jews, which he portrays as the result more than the cause of Obama’s lack of interest in helping African-Americans.

The Sanders revolution means that, rather than a full-throated celebration of Obama’s record akin to the treatment Ronald Reagan received at the 1988 Republican convention, the party’s message will include the perspective of one of the president’s avowed haters. Of course, Sanders himself has not said these things, and perhaps he is rewarding West for his campaign service. But if you are celebrating the changes Sanders is bringing about to the Democratic Party, you are celebrating the replacement of one cohort of advisers and activists with another. Sanders’s revolution means giving West’s views more legitimacy and influence in Democratic politics.