The morning after Anthony Weiner finished a dismal fifth place in the Democratic primary of the last mayoral race, he gathered the remains of his skeletal campaign staff and made some remarks. “I can’t believe I gave the press the finger,” he said, shaking his head. He congratulated us on running a strong campaign under what he called White House–level scrutiny. “I was the weakest link,” he said and bit his lip.

Some of my colleagues got misty. Others rolled their eyes. I felt numb at the end of this whipsawing run that took us from underdog to front-runner and back again in 15 weeks. “People will talk about what we did on this campaign for decades,” Weiner continued, “and I kind of want the story of how it was run to come out.”

I asked a question: “What do you want us to say when the press calls?” As his policy director, I had grown used to fending off media inquiries from the likes of People, CNN, and TMZ. But Anthony’s answer had changed. “I want you to tell the story,” he said.

The new documentary, Weiner, by Josh Kriegman and Elyse Steinberg purports to do just that. Winner of Sundance’s Grand Jury Prize, Weiner opened in theaters on Friday and is being hailed as one of the great campaign films. Kriegman, Weiner’s former chief of staff from his days in Congress, had nearly unfettered access to the candidate during the 2013 race, and the film beautifully humanizes Weiner and his wife, Huma Abedin. The camera lingers when Anthony says incredulously, “This is the worst — I’m doing a documentary of my scandal.” We witness their humiliation and desperation to get out of the trap their lives had become after his second sexting scandal. Because Anthony Weiner is a complex, funny, and compelling character, the film is, at times, all of those things too. Underneath the narrative of his rise and fall in the mayoral race are the million-dollar questions: Why did he do it and why did she stay? But while the film sheds light on the complexities of the couple at the center of the shitstorm, it does not reveal the answers to those mysteries.

The film’s view of the campaign itself is also selective and, to some necessary extent, superficial. Huge swaths of time are skipped, because they don’t fit neatly into the arc. Pivotal figures in real-life — including the campaign’s first manager, Danny Kedem — are entirely absent, presumably because they didn’t sign releases. The film uses tabloid headlines and late-night punch lines to string together gaps in the narrative, but it’s not the campaign I experienced. After the immediate impact of that second sexting scandal, which broke in late July 2013, Weiner mostly jumps to days before the election in September, leaving out a crucial and fascinating month of desperation. As Anthony’s first hire and one of the last out the door, I want to share here what Anthony emboldened us to do: tell the real story of the campaign.

I met with Anthony in January at a Cupcake Café. It was nine months before the election, and the seven-term congressman from the ninth congressional district needed a political outsider who would not leak his run for Comptroller (yes, it was Comptroller back then). A mutual friend gave him my name, and a day later we were discussing our toddlers’ nap schedules and how many cupcakes this café would have to sell to pay their Park Avenue rent. I told him I was a playwright out of Juilliard and strong with research, words, and storytelling, though I had no real political experience. I was also a fan of his politics, especially his rant on the House floor in support of the 9/11 first responders. Plus, I was a single mom up for some self-reinvention. I didn’t ask about his sexting scandal two years earlier that forced him to resign from Congress, and he didn’t ask me, well, anything. Thirty minutes later I had the gig.

For the next three months, we were what Anthony called “a two-person army of ideas.” With a daily exchange of calls, emails, and texts, we drafted his “Keys to the City: 64 ideas to keep New York the capital of the middle class.” Anthony’s a brilliant guy, passionate about any given subject. Plus, he’s funny and candid, and when all of that attention is focused on you, it’s intoxicating. That’s why voters liked him. I liked him.

One day Anthony emailed me, “btw, I’m thinking about running for mayor.” A few weeks later, a poll showed him at 15 percent in the mayoral race and he emailed again, “Game on, bitches.” It was a week after the flattering cover story on Anthony and Huma appeared in The New York Times Magazine, putting the sexting scandal in their rearview. He thought he had a strong chance of making the run-off, even if he put his odds of beating out front-runners Christine Quinn or Bill Thompson at about one-in-three (Bill de Blasio was polling around 10 percent then and not seen as a significant challenger.) Win or lose, the upshot of the run was it would turn the page on Anthony’s scandal, and ideally, restore his reputation. Plus, he had millions in the bank from his past campaigns that was his to use or lose.

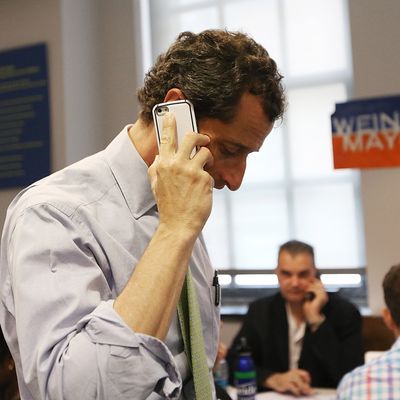

“How big do you want to play,” he texted. I said big, and he made me his policy director. Then he texted, “Are you ready for all of the ‘Who is Jessica Provenz stories?’” I thought it was funny, until I had to pass all the reporters and camera crews camped outside his apartment on May 22, the day he announced his candidacy. Inside he fielded dozens of press calls and casually conferred with Huma, “Should we invite Josh over?” Next thing, Kriegman was there, shooting his documentary. It’s one of the few times I am in the movie; I disliked working with a camera in my face, and besides, our team of two had jumped to 100 overnight and the political careerists that Anthony had suddenly surrounded himself with had sharp elbows. After experiencing Anthony’s dictatorial management style as soon as the campaign got under way and his shouts of “You have to get in my brain, Jessica,” I was only too relieved to be sidelined.

Anthony wanted to be the candidate with the best ideas, and our policy department churned out 125 positions, opting for ones that would get him the most copy. Anthony is incredibly sharp and had scary-good recall, making his positions seem well-considered, regardless of whether they actually were. After our analysis of a plan to expand ferry service showed that it was financially inadvisable, Anthony still wanted to be the “ferry mayor” so we scrapped our conclusions and handed over a poster proposing “ferry lines across the city!” It worked. Anthony’s bold ideas and delivery made him the policy wonk of the field. Even when Eliot Spitzer announced his run for comptroller, throwing our office into a temporary tailspin with the obvious threat of being a disgraced politician by association, Anthony continued to play well with the voters. He exhibited a depth and knowledge of the issues and was a candidate to be taken seriously. Plus, people loved that he was fallible and human and sorry. And that name — everywhere Anthony went, a large “Weiner!” sign followed. By mid-July, he led in the polls.

Everything crashed to a halt with sexting scandal No. 2. It was a Tuesday morning, two months after Anthony entered the race. My team was interrupted by Amit Bagga, Anthony’s former chief of staff who had skillfully inserted himself as senior policy director. He said that new sexual allegations about Anthony were coming out. But, he stated emphatically, they were false.

Anthony arrived, and soon, he and Huma were in lockdown in campaign manager Danny Kedem’s office across the hall from where I sat. Calling in was his damage-control adviser, Risa Heller, a woman whose expertise I questioned after her handling of his 2011 debacle. They were joined by Amit, soon-to-be-appointed campaign manager No. 2 Camille Joseph, Bagga, and communications director Barbara Morgan. Less than two weeks later, Morgan made headlines of her own when she used the words cunt and slutbag in what she told fellow staffers was an off-the-record statement on former intern Olivia Nuzzi, who had written about her experience in the campaign for the Daily News. (Reporter Hunter Walker, who conducted the interview, says that it was on record and notes that the conversation was recorded.)

As this dream team was hunkered down, I read Anthony’s statement online and learned the allegations that he had sexted with Sydney Leathers were true. Leathers claimed it went on through November 2012, a year and a half after he resigned from Congress to “seek treatment,” months after the happy couple were featured in People, and only two months before he and I started prep work for this campaign. I stared at the man on the other side of the glass doors. Along with the rest of the world, I had now seen his penis. As Carlos Danger, he had written Leathers sexts like, “I start to fuck you so hard your tits almost hit you in the face.” And there he sat, arms clasped behind his head, feet up on the desk. Nobody in our office knew this was coming. Nobody.

Around 5 p.m., the doors opened and the Fifth Avenue headquarters buzzed with activity. Anthony looked focused and determined. He called his nanny and said, in broken Spanish, that they would be home later, something’s come up. Then he waited impatiently for Huma to emerge from the bathroom. I happened to be teasing an intern about making a repeat gaffe on prep work when Anthony passed. He heard something I said about making the same mistake twice and flashed me a look of abject rage, and then fear.

Then he and Huma left, an entourage trailing them. The remaining staff watched the press conference live on Anthony’s flat-screen hoping for the best, but knowing it couldn’t be worse. For the first time since Anthony announced, we all went home in time for dinner.

We dropped ten points in the polls in two days. Staffers and interns abandoned ship like it was the Titanic, and the field team staged a mutiny threatening to quit en masse. When I went into Anthony’s office to discuss his new policy book, Even More Keys to the City, he was still a hard-ass shooting down proposals despite the fact that no one would ever listen to his policy ideas again. He never looked at me, he was transfixed by the coverage of his scandal playing on loop on his TV.

The next night, I got a call from a reporter at the New York Post. She wanted to talk “woman to woman.” She said a source told her Anthony and I were having an affair. My only thought was how absurd that sounded, given that I could barely stand the guy anymore. I hung up. Then I made a half-dozen calls for advice. The response was uniform: Call the reporter back and categorically deny everything. I did.

No, Anthony and I were not alone behind closed doors together giggling (did she think Anthony giggled?). No, there were no sexual relations or sexting relations — and that was not why I got the job without any political experience. No, he didn’t pay me huge sums of money to keep quiet. No, he didn’t break up my marriage. Everything tied to Anthony was untrue, but I was terrified I was about to fall down the rabbit hole of scandal after him.

I got a call from Barbara Morgan, saying she would make the story go away, and another from Anthony sounding small and beleaguered. He said everyone in his life was under fire — especially his brother and his wife. The last thing he wanted was more civilian casualties. I had forgotten he was a human being in all this, just a man at the center of a circus. He apologized then pivoted to discussing policy. “Nice try, but can we stay on the Post,” I said. “Sorry, my mind is always racing,” he said, adding he would go on record denying the affair if he had to, but that that would be giving them exactly what they wanted.

Danny Kedem called the next morning to say he had quit. When he became the campaign manager he said he had asked Anthony the hard questions like, “Did you sext any women after you resigned from Congress,” and Anthony had lied. Danny said more stories were coming out, the consultants had quit, and he urged me to do the same. He told me the filmmaker was a cool guy, but not to sign the release (Danny didn’t, but I did).

Later that night, Anthony held a team meeting. He said that in the Times Magazine story from April they were honest — that more sexting stories were likely come out — but where he had made a miscalculation was the timeline, not making it clear that things had happened after he resigned from Congress. He and Huma debated calling the reporter back to clarify this point, but they thought that would call too much attention to it. Anthony said the cycle of these stories is 72 hours, so everything would normalize soon. We had six weeks before Election Day, a lifetime in politics. After that we ate pizza and sang”Happy Birthday” to Huma.

Meanwhile, the Post story hadn’t gone away. Huma had called Rupert Murdoch’s office and Anthony had gone on record denying it, but now the reporter was suggesting it was a love triangle between Anthony, me, and Barbara. I had had enough and spoke to Anthony privately. I insisted the campaign hire me an attorney, who sent a cease-and-desist letter. Even so, I lived in fear that I would become collateral damage. There were mornings I was sick with dread, terrified I’d wake to a Post headline about me. Only then did I really understand what the guy had been through. He made a huge lapse in judgement, but something like half of Americans sext and send naughty photos. I’ve done it, and I’d be hard-pressed to find a person who’s single today who hasn’t. And so many Americans actually cheat on their spouses, something, to the best of my knowledge, Anthony never did. I realized how hypocritical we all were to make a mockery of his biggest mistake. Didn’t many of us behave just as badly or worse?

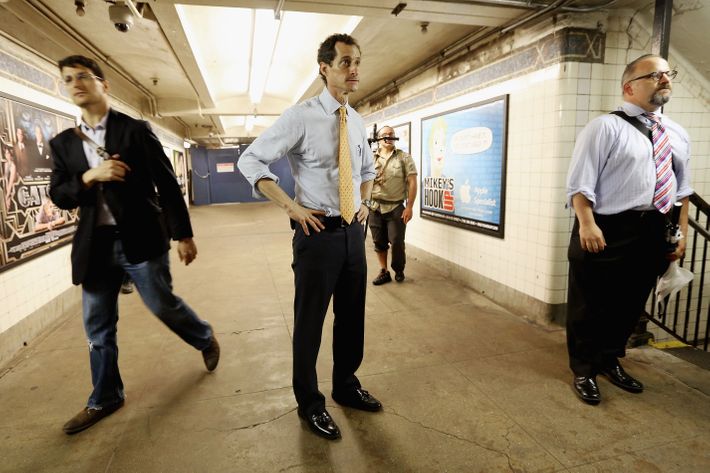

Over the next two weeks, Anthony received the highest unfavorable ratings in New York political history. The press staked out our office and followed our interns to lunch, and the Post reporter went to my ex-husband’s house in New Jersey with a photographer. Anthony, when confronted with calls to drop out, told a City Island audience: “You know something embarrassing about me, but I’m not going to quit, I’m not going to sit in the corner and cry, because I believe I have the best ideas for this city.” He got a standing ovation.

The Post never did write that false story about me. Soon they and the rest of the media turned their attention elsewhere as de Blasio rocketed to a lead in polls, having attracted many of Anthony’s fleeing voters. We amped up our policy hits to a new issue a day, desperate to change the conversation and allow Anthony some dignity. At one press conference, only three reporters showed. Finally, on an issue that we had been working on for months, not a single journalist showed. Anthony sat in his car, waiting, before eventually directing his driver to pull away. For a man who thrives on attention, I expect this was the ultimate low. This month-long period is more or less absent from Weiner.

On Election Day, of course, Leathers famously staked out our campaign headquarters. The frenzied staff, desperate to keep her from meeting Anthony, tracked her whereabouts. At one point, she fled the scene, forcing my colleague Afsaan Saleem to jump into a taxi behind her and say, “Follow that cab!” The climax of the evening was Leathers in a push-up bra outside the campaign party, forcing Huma to stay in her car lest she suffer further indignity. To get inside Connolly’s Pub where the party was being held, Anthony had to race through McDonald’s with Leathers and a pack of reporters in hot pursuit. There he gave a teary concession speech before hustling out. When he was safe in his car, he flipped the media the bird.

It had been my job to get into Anthony’s brain, but after nine months, I realized he didn’t know a thing about me. I approached him at our post-campaign party and asked, “Do you know I’m a single mom?” I wanted acknowledgment of what my family and I had sacrificed. He didn’t know. “You must feel good about yourself, accomplishing all of this,” he said, missing my point. Then the conversation turned back to him: “I’m 50 years old, and I need to find a new career.” I smiled, same old Anthony. I said good night, and I haven’t seen him since.