It’s official: Downtown Brooklyn will soon look a little bit more like Dubai. Michael Stern’s 73-story building at 9 DeKalb Avenue, designed by SHoP Architects and incorporating the air rights of the Dime Savings Bank, will reach 1,066 feet into the sky. Plenty of freaked-out Brooklynites have taken affront. But when Crain’s wrote about it, one of the first commenters’ main concerns was simply whether “thought’s gone into where the shadow’s cast.”

Ah, yes, the old shadow argument. It’s trotted out every time plans emerge for a tall tower — and has been since 1916, when the sunlight-blocking Equitable Building downtown led to the creation of New York’s first zoning code. (Which in turn led to the setback forms of the classic prewar skyscrapers.)

There is a long tradition of hand-wringing over lost light. In a New York cover story in 1981, the great urban planner William H. Whyte despaired over the giants rising on Madison Avenue as the decade got under way: “The great slabs do not just knife into the sun; they block it broadside, and down below, they make the existing shadows even darker.” In 1986, Carter Wiseman, this magazine’s architecture critic, wrote about the darkening effect of Television City, an enormous complex that Donald Trump was planning on the West Side with a 150-story tower as its centerpiece. (The big tower never went up, and the whole thing is now called Riverside South.) And just last year, our critic Justin Davidson wrote about the architect Jeanne Gang’s attempt to configure a skyscraper so it threw virtually no shadow at all on the nearby High Line. The building is called Solar Carve Tower.

Was it ever thus? Of course. Consider the critic Hamilton Mabie, who fulminated in a 1903 speech to the Harvard Club that the new skyscrapers were “monstrosities called architecture” and “unorganized masses of masonry.” The one he hated most: the immense new Flatiron Building. Twenty-two stories!

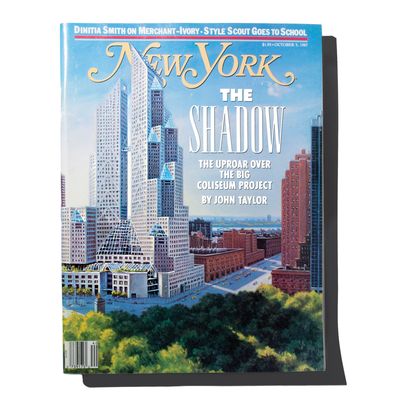

But really, the shadow-of-the-skyscraper trope has never played out so prominently as it did at Columbus Circle. In 1987, Mortimer Zuckerman’s Boston Properties, backed by Salomon Inc., laid out a plan to replace the MTA’s dumpy New York Coliseum with a twin-towered development called Columbus Center. It was to be 68 stories tall, designed by Moshe Safdie. For some reason, this particular project drove people completely nuts. Maybe it was the prevailing (shiny, loud) taste in office-building architecture, or maybe they were already getting a sense that developers ran the town. Whatever the cause, the Municipal Art Society decided to put up a fight, and figured out that the shadow of Columbus Center would, come winter, reach clear across Central Park. Jackie Onassis, Walter Cronkite, and Bill Moyers came out for the cause, and protesters with black umbrellas lined up in the park one day to trace out the building’s shadow. The Times, in its cautious way, called for the design to be scaled back, ever so slightly.

New York was not nearly so cautious. “The Shadow,” by John Taylor, led with a description that must have gladdened the umbrella-wielders: “By 5 p.m. in April, it will begin to darken the slides and swings of the Heckscher Playground — darkening, too, of course, the children playing there … In the depths of December, when the reduction in natural light has already put a portion of the population into metabolically induced depression, a stretch of the park almost a mile long … will be plunged into darkness a full half-hour before sunset by the hulking colossus.” Though the rest of the story is more evenhanded, noting the general crumminess of Columbus Circle and the need for development, the issue had been framed: Greedy developers want to eat your light and air. A couple of weeks later, the Times was similarly capitalizing “The Shadow.”

Who Won?

The public, briefly. Salomon, under pressure, quit the project. Zuckerman hired a new architect and offered up more contextual plans in 1988. Then the realestate market crashed. In 1996, the city and state rebooted, ending up with today’s Time Warner Center. It’s no smaller than the Safdie project, although it’s a better building, and Columbus Circle itself, while not exactly a civic center, is no longer actively unpleasant. (Davidson notes that the TWC’s biggest innovation turns out to have been not on the skyline but below grade. “That Whole Foods in the basement liberated underground space — they discovered the ability to get people down there. The Apple Store, in the sunken plaza at the GM building, never would have happened without it.”) As for the long shadow … well, it thins out as it lengthens, and nobody much notices it. As will most likely be true in Brooklyn.

*This article appears in the May 2, 2016 issue of New York Magazine.