For weeks before Donald Trump clinched the GOP presidential nomination, no discussion of potential “convention chaos” scenarios for Cleveland was complete without a quote from North Dakota RNC member Curly Haugland, who eccentrically maintains that all of the efforts to bind delegates to primary and caucus results are and should be for naught.

When the Convention Rules Committee meets just before the convention, Haugland is expected to offer an “unbind the delegates” resolution that will be promptly voted down. What’s more interesting is that once that effort fails, Haugland will then pursue an alternative:

Haugland plans to pair this effort with a proposal to eliminate the GOP convention altogether. His argument: If delegates are to simply cast pro forma votes based on the results of primaries and caucuses, why convene an expensive and largely meaningless gathering at all?

That is a good question, and not just for Republicans.

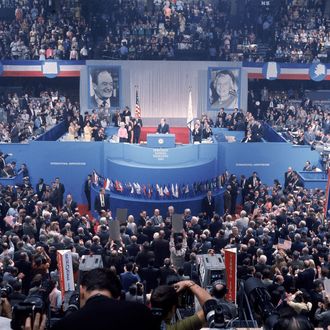

It’s been obvious for a very long time that the conventions are large atavistic events chasing an ever-narrowing window of media attention. Indeed, the momentary likelihood that this year’s GOP convention would have an actual deliberative function has made its habitual uselessness that much clearer. Yes, the conventions provide the major-party nominees with the opportunity for a high-profile acceptance speech that sets the tone for the general election. But are tens of thousands of “extras” — the delegates, alternatives, and “guests,” most of them media folk who are there to “cover” the conventions ever so briefly — really necessary for that purpose? And are three to four days dominated by hundreds of politicians in suits standing behind a podium and reading banalities (believe me, as a veteran of many Democratic convention rehearsal rooms, I can tell you that banalities are the mandatory rule for convention speeches) from a teleprompter the kind of image the parties want to project in this politics-hating era? And more fundamentally, if you were going to start all over and design an event to signal the coronation of a nominee and the beginning of the general election, would it look anything like today’s conventions? Probably not.

One might object that even without a “contested convention” this year’s events may feature dramatic and symbolically important clashes over party platforms. But the recent historical record is clear: For all the talk of platform deliberations, the odds are extremely high that the campaign controlling the convention (the putative nominee’s) will either quash, accept, or pre-negotiate any potentially troublesome planks. Most nominees would gladly surrender on any and all platform demands by primary losers — the fool’s gold of presidential politics in any event — to avoid “party in disarray” stories. And that’s kind of the bottom line: The purpose of modern conventions is to avoid trouble, and what an enormous amount of trouble the parties go through to make the conventions trouble-free!

You get the sense that if either party suddenly decided to stop having conventions, within a cycle or two we’d all wonder why the tradition took so long to die after quasi-universal popular nominating contests became the norm over four decades ago.

So what if, as nearly happened this year, the primaries and caucuses do not produce a nominee? Certainly then a convention could be scheduled to resolve the issue, though probably without all the endless off-prime-time speechifying that only drowsy C-SPAN watchers will witness. But in the 99 percent of presidential cycles where the nominee is known well before the primaries end, there’s really no reason for the parties to play dress-up and pretend they are deciding anything.

Reporters looking for something to do in Cleveland should use it to pose the troubling question to as many attendees as possible: What are you doing here?