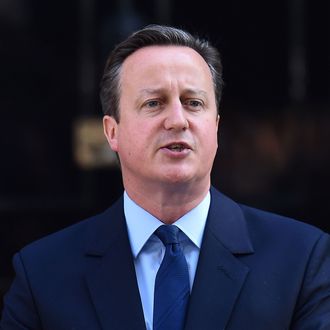

Yesterday’s shocking vote by the U.K. electorate to leave the European Union (popularly known as “Brexit”) has turned British politics upside down. Prime Minister David Cameron, who called for this referendum as a way to placate the Euroskeptics of his own Tory Party and hold off the UK Independence Party (or UKIP) nationalists storming its gates, resigned the moment the results were clear. There will be an immediate leadership fight leading up to a party conference in October, and quite possibly the new PM will hold a “snap” election. The front-runner is former London mayor (and erstwhile journalist) Boris Johnson, a national celebrity and also a leading Brexit supporter.

Meanwhile, Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn, who rather unconvincingly campaigned for the “Remain” cause, which did conspicuously poorly in Labour strongholds, faces a no-confidence vote of his party’s parliamentary members, with 55 already onboard to oust him. In Scotland — which voted heavily in favor of remaining in the EU — nationalists are using Brexit to revive their own plans for independence from the U.K., and will push for another referendum aimed at keeping their once and maybe future country in the EU. There’s similar talk, believe it or not, in Northern Ireland, though, in its case, union with the rest of its own island would be the Euro-centric option.

It’s hard to believe that just over a year ago Cameron won a smashing election victory that rid the Tories of a coalition with the religiously pro-Europe Liberal Democrats and threw Labour into a leadership crisis that eventually culminated in the election of the leftist Corbyn — sort of the Bernie Sanders of the U.K.— as leader. (It’s also been less than two years since Scottish voters rejected an independence referendum — another big test for Cameron.) But the price for Tory unity in 2015 was the prime minister’s promise to hold a binding referendum on Brexit, and in the end Cameron was undone by the European issue that also brought down Margaret Thatcher and John Major in their day.

The most discussed short-term consequence of the Brexit vote is a calamitous split in the Tory ranks. But it may be more accurate to say the Tories have long been split on the subject of Europe, and perhaps now the party can actually begin to recover, particularly since it is no longer in partnership with the LibDems. Labour may have the more serious split between a pro-Europe political leadership and a Euroskeptic rank and file, whose resentment of Eastern European immigration would be familiar to anyone looking at white working-class sentiment in the U.S. Rust Belt. More immediately, Scottish independence represents an existential threat to Labour, which needs Scottish seats in Parliament if it is ever to reclaim a majority.

UKIP is (along with the LibDems) the party most united on Europe, and Brexit is a moment of great vindication for its nationalist, anti-immigration membership. But a Tory Party led by the now-reigning Euroskeptics is in a good position to marginalize UKIP.

All in all, there’s really no telling what the political balance of power in the U.K. will look like a few months from now, much less by the next scheduled elections of 2020. Much will depend on the economic fallout, and on the skill of whoever is at the helm of government in negotiating the actual Brexit in a way that maintains some of the less ambiguous benefits of a relationship with the EU as a free-trade zone.

It’s probably fitting that one of the few prominent figures greeting the Brexit vote with absolutely no sense of nuance was one Donald Trump, who happened to be visiting Scotland this week. Trump congratulated the British people for “declaring their independence,” and suggested with characteristic self-regard that it was a development parallel to his own campaign and the shock waves that would be set off if he actually won. For people on both sides of the Atlantic who are watching markets tank in response to Brexit, that’s a grim prophecy indeed.