Donald Trump appeared on the national political stage almost eight years ago. Only then he was called “Sarah Palin.” The circumstances of Palin’s ascent came very differently. While Trump nurtured his fame for decades in the New York media spotlight and won the Republican nomination after a protracted nationwide campaign, Palin was plucked in her political youth from the most remote state in the union and presented to the party as a fait accompli. Having no chance to consider or debate her selection, Republicans defended her unreservedly. What critics saw as dangerous ignorance buttressed by anti-intellectual resentment, conservatives defended as populist authenticity, a noble victim of venal coastal elites.

The actual Palin, transparent to her handlers behind the scenes, was even more horrifyingly buffoonish than the public version. She required remedial ninth-grade-history-level tutorials on events like World War I, World War II, and the fact that there are actually two Koreas. She appeared to be mentally unstable. Some of her handlers found the prospect that she might assume the vice-presidency so dangerous that, in the weeks leading up to the election, they prepared a contingency plan to warn the public in the event John McCain had a chance to win. After the campaign, Palin’s defenders — that is, the entire Republican Party — began to slowly edge away as it became increasingly difficult to defend her erratic persona. Palin indulged conspiracy theories, like “death panels” in Obamacare and the allegedly murky circumstances surrounding the president’s birth, and praised Trump for pursuing the investigation (“He’s not just throwing stones from the sidelines, he’s digging in, he’s paying for researchers to find out why President Obama would have spent $2 million to not show his birth certificate.”). Her various attempts to monetize her gullible followers devolved into an embarrassing reality-television freak show.

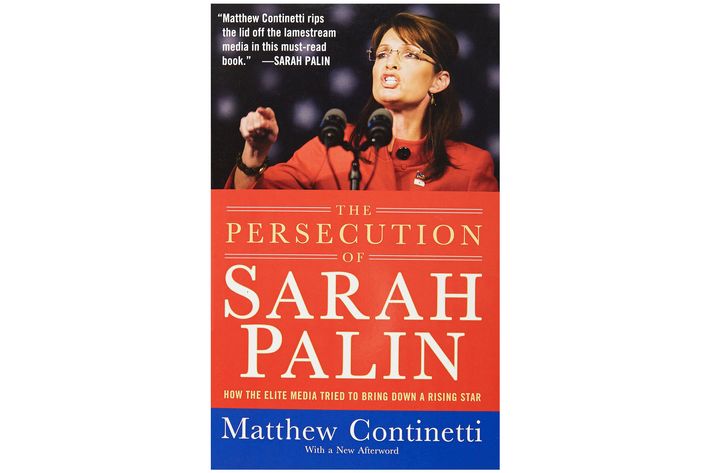

One conservative who did not abandon Palin was Matthew Continetti, who wrote for The Weekly Standard, the editor of which, his father-in-law William Kristol, helped bring Palin to the attention of Washington Republicans. Now the editor of the Washington Free Beacon, Continetti continues to nurse grievances against Palin’s critics within the party. As recently as last summer, Continetti accused the McCain staffers who denounced Palin for their “back-stabbing vindictiveness and self-seeking,” for being small enough to curry favor with “the liberal press” by “leak[ing] disparaging material about their vice presidential candidate even before Election Day.”

The rise of Trump has given many Republicans, including Continetti, a different perspective on these very same questions. Trump’s candidacy has given them the chance to debate the merits of an ignorant demagogue, rather than defend him reflexively. Many of them have decided that a president who knows things about public policy, and does not indulge conspiracy theories from email chains, has a certain charm. They have even come to view the dissent against such a candidate as an act of nobility, rather than traitorous currying of favor with the elite liberal media. And they have even begun questioning what pathologies have driven Republican voters into the arms of such patently unqualified demagogues. Continetti has a column today making the point in admirably clear terms:

It’s a joke. All of it: his candidacy, the apparatus of propaganda and grift surrounding it, the failures of governance and education and culture that have brought us to this place. What disturbs me most is the prospect that Donald Trump is what a very large number of Republican voters want: not a wonk, not an orator, not a statesman, not even a leader, really, if by leader you mean someone who persuades and inspires and manages a team to pursue a common good. They just want a man who vents their anger at targets above and below their status.

These are important questions — what failures of education and culture could have left Republican voters predisposed to the propaganda of a grifter who is neither a wonk nor an orator, and who exploits their cultural resentments? Continetti does not provide any answers. Here is one: