In the most famous scene in Goodfellas, Tommy DeVito menaces his fellow gangsters in a restaurant, pretending to take umbrage at Henry Hill (“Funny how? Funny like a clown?”) and then casually brutalizes Sonny Bunz for laughs when Bunz asks him to pay an overdue tab. But the scene that’s always stuck in my head is the one that immediately follows. A terrified Sonny meets with Paul Cicero, the family boss, and asks for protection against Tommy, who he fears is going to kill him. “What am I gonna do?” says Paulie. “Tommy’s a bad kid; he’s a bad seed. What am I supposed to do? Shoot him?” Sonny replies, “That wouldn’t be a bad idea.” Paulie gives him an icy stare in return. The suggestion of shooting Tommy was purely a rhetorical question, meant to suggest the limits of what he considered acceptable. Of course, as Sonny was saying, Paulie could have shot Tommy. That is how mob bosses (who don’t use layoffs or early retirement plans) handle recalcitrant employees. Paulie’s response instead indicated the boundaries in which he placed the dispute. Yes, Tommy was a menace, a sociopath operating outside even the loose moral structure of a Mafia family and who might very well murder Sonny on a whim. But he was a lucrative member of the operation, and eliminating him for reasons of mere moral revulsion was utterly out of the question. Paulie’s ethical calculus is contained in his question, “What am I gonna do?” He’s the boss, with near-total power, and he could do whatever he wants. He’s simply dismissing the right thing to do out of hand.

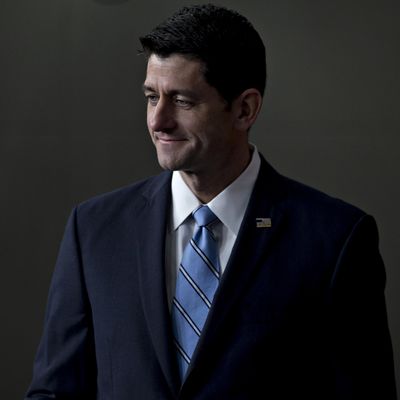

Tommy is Donald Trump, a dangerously out-of-control sociopath who defies even the hardly rigorous standards of behavior of the organization (the Republican Party). Sonny Bunz is the Republicans who fear that Trump’s cruel, erratic behavior will bring about their own (political) demise. And Paul is Paul Ryan, the effective boss of the Republican Party.

Republicans are engaged in a heated internal debate on the subject of “What should Paul do about Donald?” On the side of metaphorically shooting him are such figures as David Brooks and George Will. On the opposing side lie The Wall Street Journal editorial page and Charles Krauthammer. Ryan’s handling of Trump is a source of such intense dispute not only because of the stakes of the decision, though those stakes are very high — Ryan’s open opposition could make Trump’s election nearly impossible — but also because of what it reveals about Ryan’s own priorities.

The argument by Brooks and Will presumes that Ryan is, or should be, motivated primarily by principles like constitutionalism and social values. Will scoffs, “Whatever semblance of the House agenda that reaches President Trump’s desk is more important than keeping this impetuous, vicious, ignorant and anti-constitutional man from being at that desk.” Brooks suggests likewise: “Culture, psychology and morality come first … Ryan’s argument inverts all this. It puts political positions first and character and morality second. Sure Trump’s a scoundrel, but he might agree with our tax proposal. Sure, he is a racist, but he might like our position on the defense budget. Policy agreement can paper over a moral chasm.”

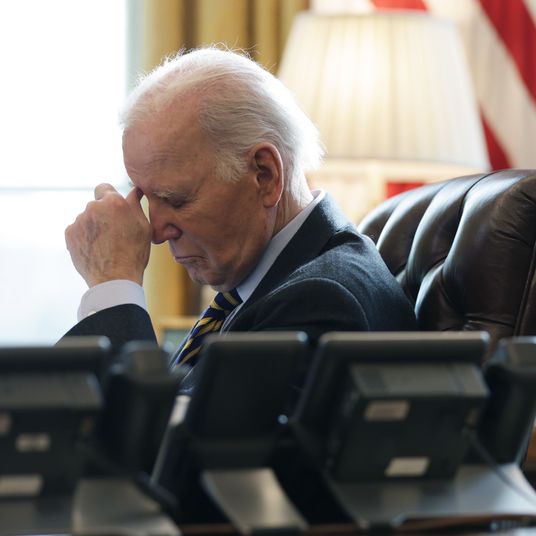

What these arguments presume is that considerations like preventing the election of an erratic, authoritarian demagogue count for more than mere “policy” or “agenda.” But the revealed truth is that Ryan’s commitment to his policy agenda defines the boundaries of his moral vision. There is a reason Ryan has written a series of budget documents as grandiose manifestos proclaiming a crossroads of civilization itself.

The Journal editorial page is known on Capitol Hill as the “Paul Street Journal” because of the personal closeness of its editor (Paul Gigot) to Ryan, and the shared commitment to supply-side economics. Its editorial defending Ryan can be assumed to closely reflect Ryan’s own thinking. Ryan needs to endorse Trump so that he can maintain a position of influence over a Trump presidency (“Conservative pundits say Mr. Trump has authoritarian tendencies, but then they should want principled leaders in positions of power to restrain him.”). One might object that Ryan’s proper role might be to denounce Trump in order to ensure he is not elected. But this would hurt other Republican candidates:

It isn’t clear what Mr. Ryan’s critics want him to do in any event. Do they really expect a House Speaker to deny support to the GOP nominee, making the Trump-Ryan division a running story through November? There’s nothing like a bloody Republican civil war to dampen turnout and produce an election rout for the other side.

What do they want him to do? Oppose Trump? And put Republican control of Congress at risk?

Krauthammer makes virtually the same argument, in virtually the same terms. “Ryan called an armistice. What was he to do? Oppose and resign?”

That wouldn’t be a bad idea. One might argue that Ryan’s obligation to the sanctity of American democracy supercedes his commitment to a low top tax rate and lax business regulation. Even if Republicans lose seats in November, they will almost certainly gain them back in the following midterms. But to presume Ryan might think in these terms is to fundamentally misunderstand who he is and what he cares about. What Will and Brooks dismiss as mere pecuniary considerations are in fact the bounds of his moral vision. Paul Ryan is not going to blow his chances for a huge tax cut merely because he’s worried about a dangerous maniac.