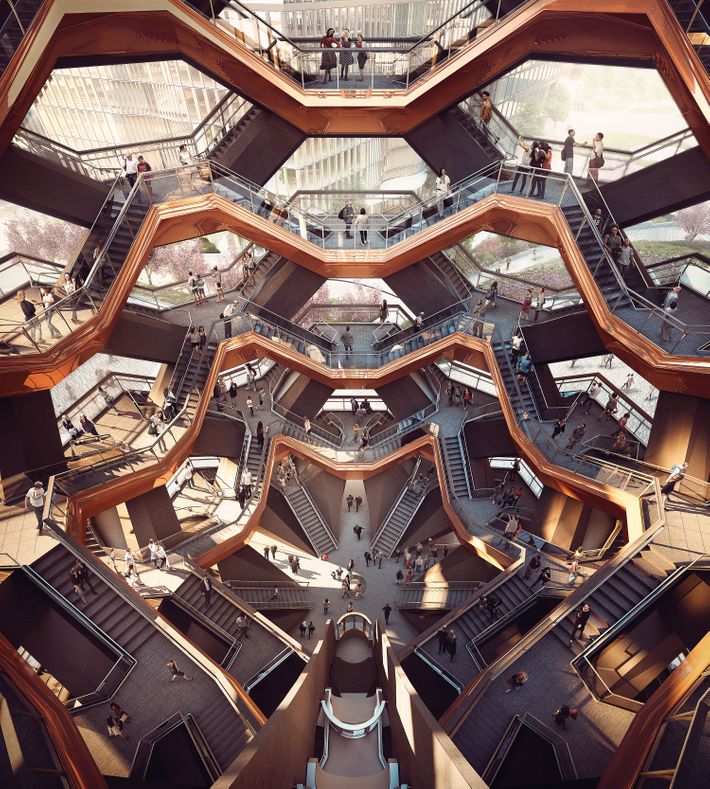

So many places you travel to, you find it would have been better if you’d come 20 years earlier,” says Thomas Heatherwick. We are looking down, from a conference room on the 41st floor of the first skyscraper open for business at Hudson Yards, on the enormous, dusty construction site for which Heatherwick has designed a great, shiny intentional-boondoggle-of-a-monument: a 150-foot-tall, at least $150 million, climbable, urn-shaped, honeycomb-latticed lookout tower and selfie stage with no other purpose than to exist that’s called, for now anyway, the Vessel.

Stephen Ross, the 76-year-old developer who runs Related Companies, wanted an “Eiffel Tower” to anchor Related’s West Side mini-metropolis. Heatherwick gave him the Vessel, the latest in a line of beguiling grand urban follies of the kind First World cities don’t really build anymore. (Heatherwick’s also the creator of that ethereal-looking park-on-stilts called Pier 55, funded by Barry Diller and Diane von Furstenberg and scheduled to be built at the other end of the High Line from Hudson Yards, as well as the planned Garden Bridge, a tree-thatched pedestrian span that is to cross the Thames.) The British designer’s offices are in London, and he travels a lot by necessity these days, with projects in South Africa, Northern California, China. “As soon as they start building office buildings, retail elements, hotels, they become very globally similar,” he laments. His job, as he sees it: “Try to in a way invent particularity.” He swipes an animation of the Vessel on his iPad. “I mean, I’m biased, but I don’t believe there are many of these …”

Video: The Future of Hudson Yards

This was in July: The design for the Vessel, which had been kept secret in order to preserve what Ross calls the “wow factor,” was unveiled to the public on September 14, complete with dancers from the Alvin Ailey company doing an exultant, razzle-dazzle high-step on the stage, and Anderson Cooper, the MC, declaring (since CNN, along with the rest of Time Warner, is moving to Hudson Yards) that he was going to run up its 15 stories of stairs for exercise every morning when it opens.

Heatherwick, who is 46, has no formal training as an architect (he has a master’s in furniture design). But he has nonetheless become one of England’s most celebrated and inventive builders. People — important, hard-to-impress people, people who write checks to help get interesting things built — tend to swoon at Heatherwick’s talent, his energy, his remarkable twee chutzpah. Ross, who doesn’t seem so easily seduced, told me: “He’s probably the most creative guy in the world today.” Heatherwick’s early mentor Terence Conran has called him “the Leonardo da Vinci of our times.” Barry Diller, who was so taken with Heatherwick that he agreed to pay to build Pier 55, has gushed that “I think he’s the most creative, interesting architect — other than Frank Gehry, whom I adore — alive. They share a kind of genius for imagination in its purest form.”

Heatherwick’s charm, in person, is soft-spoken — he almost whispers, inviting you into his creative reverie. His quietly imploring voice is at the center of his practice: He is a conjurer and explainer. And at that he is certainly better than many architects, with their stentorian academicspeak. One of his favorite personal taglines — which likely appeals to moguls of every stripe — is “Ambition is a form of creativity.”

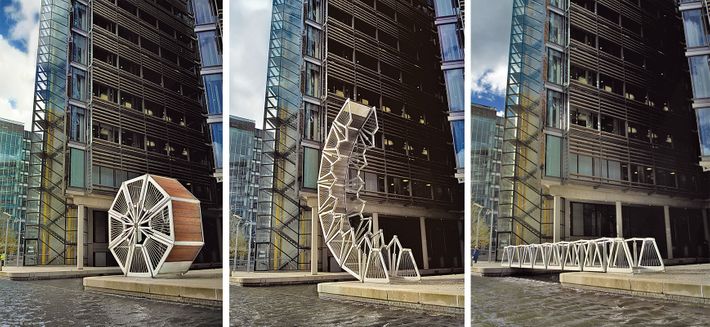

His reputation and the unusual personal cult surrounding his work are built on a series of satisfyingly ingenious architectural playthings (as well as some impishly fun furniture) that made him a design hero in pre-Brexit Britannia, including the Seed Cathedral, a jaunty 32-foot-tall square burst of acrylic rods, impregnated with seeds, which was the U.K. pavilion at the 2010 World Expo in Shanghai. It not only looked cool (like a hairy building, or perhaps a big friendly virus), it also implied a statement, or a national boast, about biodiversity. Even better known is the Olympic Cauldron from the 2012 Games, in which every country got its own unique flaming pod on a stick; all of them, when placed in the central holder, hinged together to form one big burning bunch of pods, like a flower. (Yes, it was a visual symbol of world unity, and part of it is currently rather solemnly enshrined at the Museum of London.) Then there’s the mechanical bridge on the Paddington Basin, which, once a week, adorably curls up, like a children’s toy. And the so-called Boris Bus, Heatherwick’s opulent revival of the cherished old London double-decker, which was commissioned by that city’s then-mayor, Boris Johnson. Johnson and Heatherwick seemed to find common aesthetic cause in a shared vision of a new London, which culminated, with reverberations still, in the design for the picturesquely forested Garden Bridge, a short walk east of Waterloo Bridge, connecting the gentrifying tourism zone of the South Bank with the still rather staid area on the other side, at the edge of London’s already heavily touristed theater district.

Lately, that bridge has proved rather controversial, with a grassroots movement mocking it as a “vanity project” — a vastly expensive Instagram platform for tourists, funded in part by private money (£22 million of which has reportedly gone missing), that will be closed monthly for use as an events space. (And one that, as transporting-looking as it is, is not terribly useful for transportation — you can’t, for example, ride your bike across it, and it would be closed overnight.) Johnson derided the bridge’s critics as harboring “a Taliban-like hatred of beauty.” Defending the bridge on the BBC against accusations that it was a pet project of the cronyistic “chumocracy” of British elites, Heatherwick struck a more patriotic, post-Brexit note: “It is important that our society doesn’t show that we suddenly have no confidence in ourselves, that we don’t suddenly seem like, ‘Yep, we’ve had a political turmoil, now we suddenly close up and we’re just going to go backward.’ How can it possibly be a bad thing to stitch the city together better, to create new public space that we have never had before, new views for all of us?” When he’s talked about the Vessel, he’s said he’d like it to last 200 years; he once said that the Garden Bridge is supposed to last 1,000.

There have also been complaints about the lack of transparency in the planning of Pier 55 — lawsuits, too, which Diller has suggested were funded by rival mogul Douglas Durst. But there’s no question Heatherwick’s floating hillock is enchanting, at least in renderings. And Heatherwick believes in the importance of what he is doing, of the fanciful baublelike gesture — high-tech English romanticism deployed in projects that seem to take the fairy-tale magic of the CGI sets of the Lord of the Rings films and move it into our lived existence.

On the day we meet, Heatherwick is dressed, as usual, in a waistcoat, pleated pants, and elaborately laced shoes. With his lightly graying curls, he is often described as “elfin.” Although, in Lord of the Rings terms, he looks and dresses more hobbity — specifically like Martin Freeman as Bilbo Baggins. And his manner is more than a bit hobbitlike too — unusually attentive and good-humored. He is in New York for a few days to check on his projects here. Besides Pier 55 and the Vessel, he is doing at least one apartment building for Related and, in partnership with the experienced concert-hall architectural firm Diamond Schmitt, the rebuilding of what is now called David Geffen Hall at Lincoln Center — a commission the New York Times announced in December with the line “They didn’t choose a starchitect.” Considering he is also designing the massive new Google headquarters in California, in partnership with Bjarke Ingels, that just might have been the last time that could be said of him.

Heatherwick styles himself in the manner of a Victorian tinkerer — an inventor, grounded in the artisan’s iterative, “maybe it will blow up in your face” derring-do. In fact, he once said that architects — they of “white paper, white desks, and dull computer screens” — didn’t understand how their buildings lived in the actual world. “For me, every one of our projects is a research-and-development project. Everything that we start is something that we don’t know what the outcome is going to be.” This hands-dirty ethic is beguiling, perhaps especially for patrons — sorry, clients — impatient with architects with less flexible agendas.

Related is one of the most important of these new clients, and one day in August, Ross meets me to explain the Vessel. We’re in a conference room in his headquarters in the Time Warner Center, overlooking Columbus Circle (Ross lives upstairs, and both he and Related are moving to Hudson Yards). Around us were several models of Hudson Yards: a 17 million–square–foot, 28-acre city-within-a-city on what was, until quite recently, the postindustrial edge of Manhattan (and, not so long before that, as observers of sea-level trends in this era of climate change have pointed out, marshland, which might make Heatherwick’s worry about 200 years seem a bit quaint).

Ross made his money developing affordable housing but invented something new — at least to New York — with the Time Warner Center: a huge, multiuse complex of offices and apartments over several levels of retail that draws people inside to shop and eat. And Hudson Yards is essentially the Time Warner Center at larger scale. There will be a mall with the city’s first Neiman Marcus and many towers of great height, all designed by brand-name architects, and the enormous telescoping performance and exhibition space called the Shed (née the Culture Shed), designed by Diller Scofidio + Renfro (with the Rockwell Group). This is all facing a privately owned and maintained piazza, on which the Vessel will be placed, like an enormous flowerpot. It will be as tall as the mall and a bit taller than the Shed.

The idea of putting a tower right in the middle of the plaza was not at first Heatherwick’s. It was part of the 2012 proposal made by the landscape architect Thomas Woltz (his was meant to be only 80 feet tall). Ross told me that he’d originally considered Heatherwick to design the “pavilion,” a kind of café on the western edge of the plaza, but he and Ross hit it off. Ross reportedly considered sculptors like Anish Kapoor, Jaume Plensa, and Richard Serra for the honor but worried that whatever they produced would seem familiar, another big work by someone famous — “Been there, seen that,” as he put it succinctly.

“We spent hours talking about what I was trying to achieve,” remembers Ross. Which was, in effect, a feeling: “What is the heart of New York? Rockefeller Center during Christmastime. If you live here or you are visiting, that’s where you want to go. So I said: I want to create a 365-days-a-year Christmas tree. People will want to be here and come here and be excited.” (At one time, Ross also envisioned a “modern-day Trevi Fountain there,” but the point is that he wanted something for the ages.) And to Ross’s mind, Heatherwick’s big, shiny, climby whatever-it-is was just that. “I didn’t see in my mind what he designed, but when he showed it to me, everything clicked,” he says. Not everyone at Related was sold on it, he says, but, in the end, Ross is the boss.

“The public doesn’t have any idea of what Hudson Yards is. Nobody has a real idea of what it really means — what the impact will be for the city going forward,” Ross says. “It will be the new center. You have these great corporations moving here, and then you have this.”

But there is also something else going on here: a new type of city-as-spectacle. Take the mall: “I mean, retail is dead. But what do people want out of their retail? Entertainment,” says Ross. “No matter what you hear about how bad retail is, you can’t walk down Fifth Avenue,” it’s so filled with people thronging the grand flagships of the world’s great shopping brands. “This is what the public wants.”

He looks at the Vessel. “Everybody else in my firm had a concern with it, and nobody else wanted to do it. How are we going to build it? What is it going to cost? And it cost twice as much as I estimated, but it didn’t matter. It was so important to this project. And what I’ve done is show it to all these corporate executives,” he says, to help convince them of the placeness of this new place. “That was the whole thought process. And I knew that it was so iconic, so different, so unique, and it offered a participation for the public. And the monumentality!” he adds. “When you do something so monumental, it will affect human behavior.”

I ask Ross if it’s close to what Heatherwick originally showed him. “Not almost — exactly.” He pauses. “We had to tweak it little bit to make it buildable.”

Heatherwick grew up in what he’s described as “an old, shambly, rambling house” in North London. His mother owned a jewelry-and-beads shop on Portobello Road. He’d described his bedroom as a “workshop” where he’d play with old electronics and other junk. His father gave him books about ingenious Victorians — people like engineer and inventor Isambard Kingdom Brunel. He thought he wanted to be an inventor but then “discovered you couldn’t study inventing!”

In August, I visited his headquarters, near King’s Cross Station in London (there are two other offices now to accommodate the nearly 200 people who work for him). It’s a large, open, concrete space that looks more university than corporate, tucked away behind a TraveLodge — you enter through an iron gate on the side of the building. “We like that it’s a bit hidden,” said Stuart Wood, the firm’s “head of innovation,” as he toured me around the space.

There is a large, woven, bowl-shaped boat hanging at the entrance, one of many oddball objects shelved around the room. Some were brought back from travels, like the traditional Japanese good-luck figurine of a cat waving, or the alligator made out of bread, now lacquered for preservation; others are strange expired implements or what appear to be parts of musical instruments, mainly from the collection of a man named David Usborne, who was interested in “curious tools,” most no longer used (“orphans, misfits, and rejects of industrial change and human development,” as Heatherwick wrote in an introduction to a book about celebrating them called Objectivity).

Wood, who is also not trained as an architect, has been working with Heatherwick for 14 years. When they met, Heatherwick “struck me as someone who wasn’t interested in the current design trends,” Wood said. “He was interested in making and getting things built and exploring things by making. To find exciting and daring outcomes.”

Of course, the more daring, the more they get pushback. Not everyone wants to live amid even non-clichéd buildings, however playfully benevolent their intent. But Heatherwick has placed himself in a position of neo-Romantic critique of exactly what it is that has been so successful for starchitecture over the last decade or so: the social-climbing need to imbue cities with globalist allure by making them look like other first-class places. Heatherwick’s idea: Our most prosperous cities could use a dose of whimsy to help cut the relentless commercialism driving them to feel more and more like a place for an abstract idea of a global citizen but maybe not for actual people.

And, as Heatherwick shows me, running through a video demonstration of the Vessel on his iPad at Hudson Yards, they wanted this project above all else to engage citizens — in this case by inviting them inside to climb around, look at each other, and, presumably, take photographs. “We didn’t have the self-confidence to do something which could sit there for two centuries which people just looked at,” says Heatherwick. “We felt that offering real amenity to someone could be more meaningful. And we thought: Do we do a water feature? They often don’t work, and the water blows around.” And so: “How do you design spaces which encourage what people enjoy?”

He decides to play for me the video he showed Ross to persuade him: a super-cut culled from old movies and presumably YouTube videos of people on stairs — dancing, running, creeping. The soundtrack includes Irving Berlin’s “Steppin’ Out With My Baby” (“Steppin’ out with my honey / Never felt quite so sunny”). The video peaks with Rocky running up those stairs in Philadelphia.

“Is this a piece of infrastructure? Is it a playground? Is it a fitness device?” Heatherwick asks. It’s not clear actually what his answer is. “To my mind, this is an extraordinary piece of commissioning. Whether you like it or not.”

*This article appears in the September 19, 2016, issue of New York Magazine.