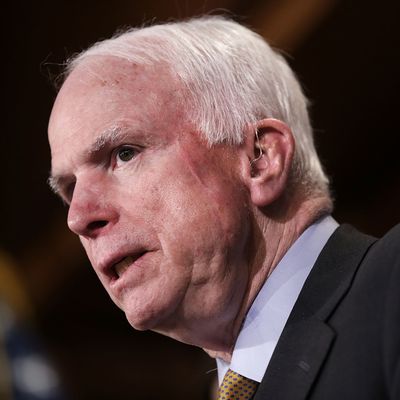

When Senator John McCain publicly promised that Senate Republicans would extend their blockade of Barack Obama’s Supreme Court nominations through Hillary Clinton’s presidency, the significance of this ominous step was largely obscured by the generally toxic partisan atmosphere of this presidential election cycle, including the fact that Donald Trump is already accusing Democrats of stealing an election that won’t happen for three weeks.

But McCain’s statement actually represents a historic moment — a departure from norms that could well lead to the death of all but the most token signs of bipartisanship in Washington. Only a very few Supreme Court nominations have been rejected by Congress over the years. While divided partisan control of the presidency and Senate has made SCOTUS confirmations trickier, it has hardly closed the door: A Democratic-c0ntrolled Senate has confirmed 11 nominees for the Court made by Republican presidents. There certainly never has been a time when senators of one party have categorically refused to consider, sight-unseen, SCOTUS nominations by presidents from the other party.

McCain’s “promise” means the 4–4 ideological deadlock on the Supreme Court following the death of Antonin Scalia could continue until the Senate and the White House are controlled by the same party. As a practical matter that means, as long as the empty seat remains unfilled, SCOTUS may continue to defer to lower courts on critical issues ranging from executive orders governing immigration and energy policy to state abortion restrictions. It could also leave the law unsettled for extended periods in cases where lower courts are divided.

In the past, such circumstances might have led to the appointment of either “centrist” justices who offended neither side on key issues, or “stealth” justices with too little in the way of a paper trail or announced positions to arouse opposition. But more recently political partisans have lost any reticence about demanding subscription to litmus tests by potential federal judges — much less SCOTUS justices. And now we are to the point where being appointed by the other party’s president is enough to label a jurist as a presumed enemy.

Indeed, McCain’s “promise” is significant even if Republicans lose control of the Senate. Obstructionist Republican senators would almost certainly use the filibuster to block Clinton’s SCOTUS nominations even if they are in the minority (they will certainly have more than the 41 seats necessary to defeat a cloture motion). That in turn would likely convince Democratic senators to complete the chore of killing the filibuster — a project they started in 2013 when they eliminated the obstructionist tactic for confirmation of executive-branch officials and judges for the lower federal courts. Assuming Republicans try to maintain — with a standing filibuster threat — the 60-vote Senate threshold for passing regular legislation, it’s probable that a Democratic majority would reimpose Senate rule by a simple majority vote in every circumstance.

You see where this is all headed. We are on the brink of a new era in which bipartisanship is functionally dead and divided partisan control of the federal government keeps anything significant from happening. That is significant not for the reasons we so often hear — the demise of those wonderful days when the good old boys of both parties got together over drinks and cut deals without regard to party or ideology — but because divided government is the rule more often than it is the exception in our system. Indeed, since Ronald Reagan became president, periods of “trifecta” control of the executive and legislative branches have been limited to the first two years of Bill Clinton’s presidency, four years in the middle of George W. Bush’s presidency (plus a brief period in 2001 before Jim Jeffords switched parties and gave control of the Senate to Democrats), and the first two years of the Obama presidency.

That’s why it is a very bad sign for a functioning federal government when a supposedly “centrist” Republican who used to take pride in co-sponsoring bipartisan legislation on subjects ranging from campaign-finance reform to greenhouse-gas emissions is announcing in advance as a matter of principle that a Democratic president can forget about what used to be a routine political process.

Some observers seem to believe divided government is a reflection of deep ambivalence among the American people and/or a desire for “checks and balances” between the branches. But the truth is, Republicans have a built-in advantage in the Senate thanks to the disproportionate power of small-population states, and whichever party controls the decennial redistricting has an advantage in the House (currently the Republicans).

Unless something changes soon, periods of productive domestic-policy-making and fully staffed executive agencies and federal courts will be limited to those relatively rare occasions when one party or the other holds a “trifecta” and can essentially operate the federal government like a parliamentary system. The only other option is to rely on regularly expanded executive powers, and that is something no one — in principle, anyway — wants.