On the first of December, three decades after the disease first hit the city, the New York City AIDS Memorial will open at ground zero of the epidemic — St. Vincent’s hospital in Greenwich Village, now closed, where patients once flooded the rooms and spilled out into the surrounding corridors, turning the genteel facility very suddenly into a kind of war zone.

All told, more than 100,000 New York men, women, and children have died of AIDS, and the memorial is built in their names. But it reminds us, too, as all memorials do, of how much has already been forgotten.

In conceiving the project — and choosing the site — the urban planners Christopher Tepper and Paul Kelterborn were inspired by an article in New York lamenting that there was no memorial yet in the city and suggested that, as a result, the site of the hospital itself, “the bland sarcophagus along Seventh Avenue, hold that place.” The story was by David France, who would later direct the award-winning 2012 found-footage documentary How to Survive a Plague. Here, in an excerpt from his upcoming history of the same name, to be published by Knopf on November 29, he recalls memories of the plague years — and many of those no longer here to tell their own stories.

Summer 1981

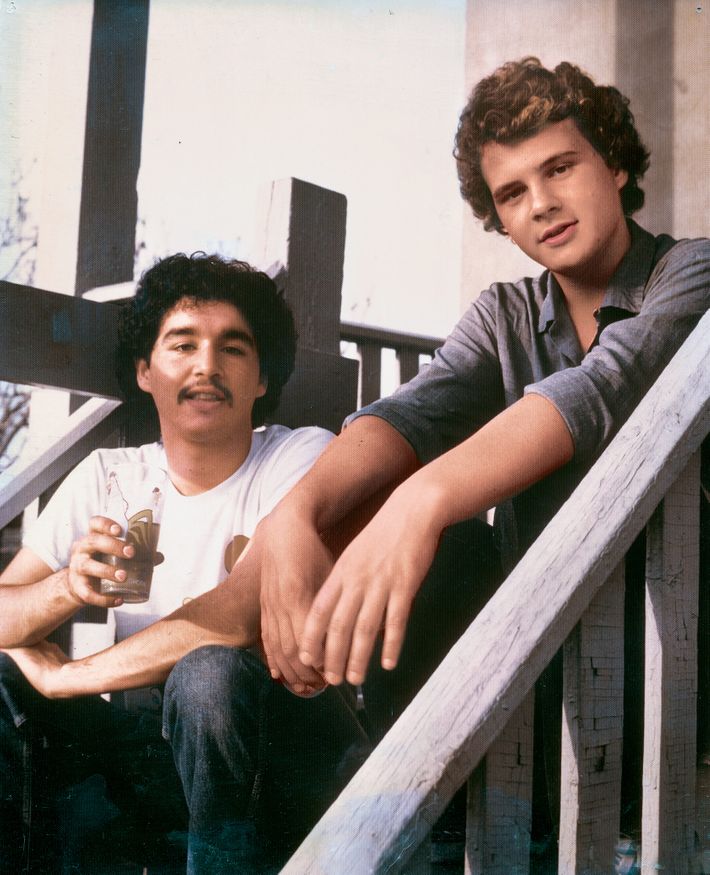

I had arrived in New York City for the first time for a college internship at the United Nations and a chance to explore Christopher Street, the mountaintop of gay life. I was not yet comfortable there. But Manhattan struck me as a city of promise, at once grimy and magical, where people could hide and be found. My college roommate Brian Gougeon, an artist, and I took up in a tiny one-room apartment in midtown, sleeping chastely on opposite edges of a narrow, lumpy bed.

Our timing was unfortunate. Just two weeks after unpacking, on the Friday of the Fourth of July weekend, the New York Times carried the first news of the plague. “Rare Cancer Seen in 41 Homosexuals,” ran the headline. The cases were concentrated in Manhattan, with a few in the San Francisco Bay Area as well, and consisted of violet-colored spots appearing somewhere on the body, easily mistaken for bruises though they were sometimes raised and textured. One in five of the affected were already dead. The article noted that “most cases had involved homosexual men who have had multiple and frequent sexual encounters with different partners, as many as 10 sexual encounters each night up to four times a week. Many of the patients have also been treated for viral infections such as herpes, cytomegalovirus and hepatitis B as well as parasitic infections such as amebiasis and giardiasis. Many patients also reported that they had used drugs such as amyl nitrite and LSD to heighten sexual pleasure.”

I later learned that men who read the paper on the ferries to Fire Island that day, having recognized themselves in the story, spent the weekend examining one another’s flesh. They found purple lesions by the dozens. It was possible to stand on those boardwalks and pool decks and beaches that weekend and foretell the whole terrible future. But stuck in midtown we thought, at the time, that our economic marginality put us out of reach. What became a disease of the poor began by assaulting the gay bourgeoisie — as a popular ad described them, the “Beautiful People of the Fire Island Pines.”

Winter 1983

It was the worst blizzard New York had seen in two generations. Twenty-two inches of snow fell, taxis and subways froze in their tracks, and the furnace in my building failed. I called Brian and begged for temporary shelter at the place he now kept alone, in Hell’s Kitchen. He sounded awful. He’d been in bed for almost two weeks, so debilitated that lifting the phone left him panting. “It’s like the flu, times a thousand,” he whispered. “I’ve got the strength of Saran Wrap.” When he saw a doctor, she diagnosed a shocking multiplicity of infections, most of them sexually transmitted. He also had painfully swollen lymph nodes along his jawline, beneath his arms, and in his groin. But they didn’t seem to alarm her. One of his infections was mono, a common cause of lymphadenopathy. She said her nodes would be the size of strawberries too, if she were as sick as he was. “When it rains, it pours,” he said.

I was leaning on his buzzer within the hour. He greeted me at the door in his underwear, almost six feet of slouching and clammy flesh. His fever was still climbing. When he turned weakly and headed back inside, I could see he had lost weight — his shoulders were like a coat hanger. He headed straight to bed and slumped to the mattress we would share that night. Though he parroted his doctor’s cheery optimism, I sensed he was afraid, and that scared me. Still, I wanted to believe he was right. I served him some egg-drop soup and administered alcohol rubs, stroking a cloth along his baking flesh. I let my fingers learn the shape of his massive lymph nodes — the size of walnuts, hard and sensitive to the touch. “I think they’re shrinking,” he winced. “From the antibiotics.”

His temperature soared and sank through the night and sweat poured from his body, leaving us both in puddles. We changed the linens twice, then wised up and made him a nest of towels to blot the stream. Much later, experts would name this the “seroconversion flu.” Most people with HIV get the same crushing symptoms in the first weeks of infection. We didn’t know that then.

And we did something that night that I have not been able to easily explain. In a feat of exquisite timing between Tylenols and linen changes, he reached for me, and with the precautions of a scrub nurse I made love to him. Such intimacies had never been a subtext between us before. Now, as 24-year-olds in a treacherous city, below the shadow of plague, we felt a need. Afterward, ironically, I was a little less frightened, and I think he was too.

I ran my thumb over his lip. “I love you, Brian,” I said. “Be careful,” he replied.

At the time, I didn’t have serious concerns for my own health. And I don’t want to overstate our sense of impending doom. It took two years and almost 600 dead before the Times put a story on the front page. The Village Voice ran a feature that called the danger overblown and was nearly silent otherwise. For news on AIDS, you would have to read the New York Native, where I had just begun working as a reporter.

Summer 1983

Brian and I watched the first broadcast report together on my small black-and-white TV. “It is the most frightening medical mystery of our time,” Geraldo Rivera said, leaning toward the camera. “There is an epidemic loose in the land, a so-far-incurable disease which kills its victims in stages.”

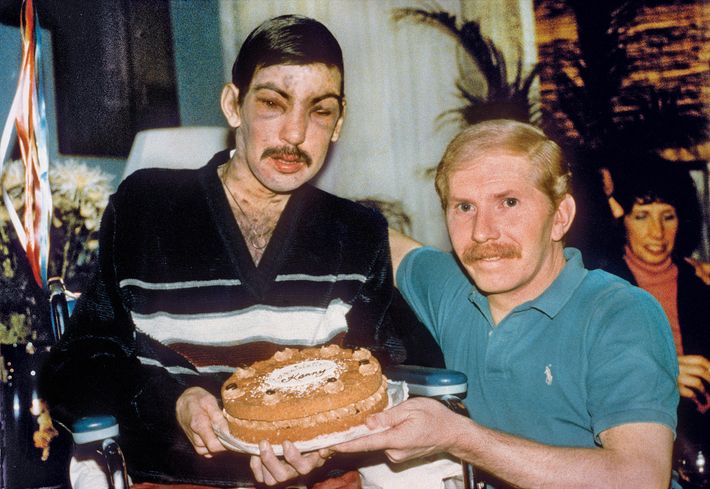

And then appeared the face of a man in grotesque medical distress — a freelance lighting designer named Ken Ramsauer, age 27. In an old photograph, he looked as polished and angular as a shampoo model. Now, his head appeared swollen nearly to the brink of popping; his eyes vanished behind swollen muffins of flesh; oblong purple marks covered his skin. He was confined to a wheelchair, having just returned from the hospital, and hung his head weakly. A friend handed him a glass of water, which was almost too heavy for his trembling arms. “One night I heard two, I believe, nurse’s aides — not the actual nurses — standing outside my door sort of laughing,” he said.

“What did they say exactly?” Rivera asked.

He blinked his slivered eyes and looked down at the water glass in his scarlet fists, remembering: “I wonder how long the faggot in 208 is going to last.”

Four days later, I opened the paper to discover that Ramsauer was dead. When I read that a public memorial was planned at the Bandshell in Central Park, I asked Brian to go with me. “I’m just staying out of the whole thing,” he said, meaning AIDS. “Worrying isn’t good for your health. And it does nasty things to your art.”

Instead, I went with another friend. That evening was unusually still and hot. As we approached the service from the south, beneath a vaulted canopy of American elms and a row of towering statuary, a macabre scene confronted us. The plaza was crowded with 1,500 mourners cupping candles against the darkening sky. A dozen men were in wheelchairs, so wasted they looked like caricatures of starvation. I watched one young man twist in pain that was caused, apparently, by the barest gusts of wind around us. In New York, there were just 722 cases reported, half the nation’s total. It seemed they were all at the Bandshell that sweltering evening.

My friend’s mouth hung open. “It looks like a horror flick,” he said. I was speechless. We had found the plague.

From there, it was an avalanche. A Friday or two later, a colleague from work ran out the door for a weekend of social commitments. He looked as healthy as a soap-opera star, which he aspired to be. We never saw him again. I heard from a mutual friend that he was found dead by neighbors the following week, shrunken and hollow, in a room washed in his own feces.

Fall 1983

It wasn’t until I traveled back to Michigan and spent the holidays in the shag-carpeted bedroom of my unhappy childhood that I saw how three years in the city had changed me. I was no longer the man who hid and lied to myself and to others, always alert to the potential for physical violence. Now I walked and talked in a way that was natural for me.

But my equilibrium was fragile outside the bubble of the gay ghetto. In my daily rounds through Alphabet City, it was possible to go for weeks with only the briefest encounters outside of my kind — the silent Korean woman who pushed a loose cigarette across the deli counter to me, the tiny Ukrainian couple on their daily path to church, the junkie who trembled pleadingly in the hallway outside my apartment door, a needle dangling moistly from his neck. Our ghettos may have occupied the same geography, yet we were all but invisible one to the other.

Back home in Michigan, I felt as conspicuous and alien as ever. Almost nobody there was out of the closet. Social scientists estimated there were 80,000 gays and lesbians in western Michigan, but they had no public spokesperson, advocate, newspaper, organization, or meeting center. With notepad in hand, I visited gay bars there for seven consecutive days. I spoke to scores of men and women, and only one — the dandy bartender at the Carousel — would tell me his real name: Tony Denkins. “But if you call me ‘the Queen,’ ” he added, “they’ll know who you mean in any bar in town.”

When I learned that the county’s medical epidemiologist was speaking at the local community college, I attended. On the bulletin board in the lobby was an announcement for a student group that stated, for no apparent reason, that none of its members were gay. Above the urinal in the men’s room, in thick marker, someone had written, “Kill a homo a day and keep the AIDS doctor away.” Out of curiosity, I entered the adjacent stall to scan the graffiti there. “If I find a homo in the bathroom, I’ll cut his balls off and stuff them in the faggot’s mouth,” one said.

Through a support group for parents of gays, I was introduced to a mother who had a sick son at home. Even talking to me over the telephone terrified her. I only knew her by a pseudonym, Edith. Her son had come to live with her after being diagnosed, she told me. “We can’t afford to have anybody know about this or we’ll lose the apartment. Then where would we go?” With great courage, she gave me her address. “And if you see anybody in the driveway, don’t come right in. Drive around the block, anything.”

A light snow fell on the morning of our appointment. Edith pulled me through the door quickly. “There are young people living in the building,” she said, pinching open a curtain to patrol the front sidewalk. She turned to me. “Okay, young man,” she said. “First show me identification.” I did. “Now,” she said, “I want you to sit down right over here, before anything else, and write on this paper that nobody will know who we are. Nobody.” A pad and pen sat on the kitchenette counter, past the cloistered living room. I walked past her son, half in shadows on the old family sofa, and did as requested. Only then could I introduce myself.

He was emaciated, maybe under 100 pounds. He balanced his cadaverous frame on two feather pillows to reduce the pain. “I thought about what name you should use for me,” he said in a hollow voice. The effort caused him to grimace. “Jim,” he said. I took his hand and sat at his side.

His mother settled into a recliner, protectively. “Only family members know what he’s got. It’ll remain that way,” she said. “And his friends from church. They call him and come to visit. But nobody else. You just don’t know how they’d react.”

“Metropolitan Community Church,” Jim specified. He attended the gay congregation, no longer submitting to the steely Christian Reformed Church in which he was raised, and which enforced a policy that “explicit homosexual practice must be condemned.”

Jim had traveled to California some years before and had enjoyed himself there. So when the symptoms came and sent him to the local hospital, he had almost been expecting them. The doctor gave the news to him and his mother at once. The first thing Edith did was to have the phone in his hospital room disconnected so that no one would find them there. They had been in hiding in their small apartment for almost a year now, and planned to remain in hiding until there was no longer a need. “When we write his obituary, it’s not going to say anything about AIDS — it’s not going to request donations to any AIDS group,” Edith said.

“But I’ll be dead already,” Jim protested in a weak and angry voice.

“I grew up in this town,” she said with forceful midwestern determination. “I went to school here. No, it will say ‘Give donations to the Christian Reformed Church.’ ”

He didn’t object — why bother? “I think about what it’s like to die. I think about my funeral. Who’s going to be there, things like that. I’ve asked people to sing …” He paused and let out a gasp, remembering how painful it was to extend the invitations. “I’ve asked people to sing at my funeral, in the church, and that’s hard.”

“Tell him what music you’ve chosen,” his mother said.

“I’ve picked out one song. ‘The Lord’s Prayer.’ ”

“Tell him the other.”

He shook his head. “I’ve changed my mind,” he told me, whispering now. “I was going to have ‘Amazing Grace,’ but now I don’t know.”

Summer 1984

At St. Vincent’s, the emergency room was visible behind enormous windows on the corner of West 11th Street and Seventh Avenue. Before the crisis exploded, how many hundreds of times had I walked past the window oblivious to the dramas enacted there? Now I found myself choked with panic anytime I came near. One sticky afternoon, I slowed to measure the epidemic through the plate glass, praying to see only strangers. Three-quarters of the seats were filled. Scanning the rows I could see that every third or fourth man had “the Look” — sunken cheeks, sparse hair, eyes that showed fear, shoulders that bent in pain. One, all spots and bones, balanced painfully on a pillow he’d brought along from home. Another seemed to be dozing; his head was cocked backward onto a companion’s arm, and his mouth and eyes were both wide open. The blind, like horses and snakes, don’t need to close their eyes to sleep. That was my experience with early AIDS — I stood on the sidewalks of the plague, grateful to not enter its tower.

That changed when Tom Ho took ill. Tall and thin and always in white denim jeans, Ho was the assistant art director at the Native and my closest friend there. We were the youngest on the editorial staff, both 25. I found Tom’s room at the elbow of a long hallway inside Lenox Hill Hospital. He was propped up in his bed and staring sluggishly out the window, his face still a topography of youthful acne. He was somewhat embarrassed to see me and the box of chocolates I held up in my defense. His voice expressed amazement, as though he were recounting the events in a film: how he had drenched his bed with sweat, then his own feces, which emptied from him violently; how the pneumonia burned his lungs and robbed his mind of oxygen; how he hadn’t told his parents — could never tell his parents. He was born to immigrants, and all that entailed. “I was the kid who grew up in the back of the Chinese restaurant at the strip mall. Doing my homework, folding napkins. They never let me out of their sight, never let me go to another kid’s house. I celebrated my birthdays there, all alone with a cake.” He straddled three worlds with no overlap: China, America, and gay. And now a fourth: the world of the plague. “They have no idea I’m gay — that alone would kill them.”

He stared through the window for a long time. “The only option I have,” he said finally, shaking his head, “is to beat this thing.”

He didn’t lack an ability to situate his plight in the epidemic’s unforgiving time line. “Who do you think will be next?” he asked me. He speculated about Gary in advertising and Bruce in the art department. “Bruce is getting skinny, did you notice?” But that was Bruce’s usual appearance; he never did contract AIDS.

“How about Peter?” I asked. “He’s been out sick a lot.” He smiled. “If Peter escapes this, it’s not contagious.”

I left the hospital as if he were already gone. The look in his eyes seared me, yes, but I was not yet numb from death, just terrified of it to the point of hypochondria. I would never see Tom Ho again, to my lasting shame.

I immediately made an appointment with a physician for a complete physical, and release, hopefully, from fear. She understood my panic and offered comforting words, but the antibody tests, far from reliable as they were, were not yet approved for clinical use. Instead, she poked my arm with a four-prong purified protein derivative test, originally designed for tuberculosis but being used by doctors as an imperfect AIDS test. In patients with no immunity whatsoever, the four pricks would leave no marks. She sent me home to hope my immune system would create bumps. To my relief, marvelous, plump boils appeared on my arm.

Spring 1985

In the East Village, where I shared a run-down apartment on Avenue C with an experimental filmmaker, the scene was grim; every building was a microcosm of the plague. Two floors above our apartment, a slender redhead from Georgia in his early 20s fell into a drunken tailspin following his diagnosis. For the several weeks before his family came to collect him, he lamented his fate operatically in our living room, incapable of steeling himself for the battle. At a time when examples of surprising grace and fortitude dominated, his reaction, however understandable, stood out. His sobbing was a tropical squall. We never heard from him again. Across the hall, my neighbor exiled her husband after a bout of pneumonia won him a month in the hospital and a discharge slip that said AIDS. When he tried to return home, she met him in the hallway with a scorching rage over his admitted drug use and, as their two young daughters screamed in confusion, refused him entry. Day after day, he returned seeking forgiveness she was too panicked to grant. One morning, I found that he had made a nest for himself in the hallway between our doors, heartbroken and desiccated, as close to his girls as he was allowed.

“Are you all right, Juan?” I asked. “Can I get you anything?” I had to lean in close to hear his reply.

“My bones hurt,” he whispered, shifting painfully from one emaciated hip to the other. He pinched at his yellow bedroll, unable to turn it into the cushion he longed for. His voice was hollow and raspy, the unmistakable sound of PCP.

“Do you have a doctor? Anyone I can call?”

He shook his head. “At the VA, they told me to go home to Puerto Rico to die. But how?” He stared at the door.

A sudden pain contorted his face. He gripped his abdomen and gave a look of terrified foreknowledge. But there was no time — his bowels emptied with a terrible force, painting a mandala of excrement on the floor where he sat.

“Let me get you some help,” I said. Reaching around him, I pounded urgently on the door of his old apartment.

“No, no, no,” he cried out in embarrassment. He whispered an incantation in Spanish meant to spare his daughters the sight of their befouled father. He managed to get to his feet, stroking the hallway clean with his bedding, and on fragile legs carried his shame down to the street. He need not have fled. His wife never came to the door.

Winter 1987

Gary Petkanis called to say he had been diagnosed. Petkanis had been my confidant at the paper, and my occasional companion on the town — he was the person who carefully scoured the day’s mail for club invitations, and pocketed them for us. He delivered his news in a tone that seemed strangely ebullient. When I responded gravely, his gentle laugh interrupted me. “It’s not that bad,” he said. “I just wanted you to know how much I admire you, and would like you in my life at this weird time.”

I made a vow to him — and to myself, more tentatively — to be his “weird-time” partner. We spoke nightly on the telephone and saw each other several times each week. After movie nights or concerts in Central Park, we sometimes went back to his apartment on the Upper West Side for Jeopardy! or crossword puzzles, or for reading aloud the increasingly bizarre headlines from the Native through fits of laughter. We talked about the movement and our leaders, such as they were, and reviewed and critiqued the evolving liberation agenda. His politics were driven by wise intuition, and always mediated by self-deprecation about the place of “party boys” like him in the cause. We talked so late into the evening on a few occasions that he threw a fresh towel at me and invited me to stay. He said he was counting on me for continued distraction, that when talking with me about politics, he sometimes forgot about death. On those nights, lying beside him, I never for a moment stopped thinking about death.

Spring 1987

It had been months since I had last spoken with Brian Gougeon. He had moved to Chicago and had stopped returning my phone calls. Instead, he answered via ornately decorated postcards, devoid of personal news. Then, just after his birthday in July, Susan Wild, a mutual friend from college, called to say he’d been admitted to the hospital with pneumonia and toxoplasmosis. “He asked me to come help him get to the hospital,” she said. “He wanted to take a shower first but didn’t have the strength — he’s so thin, David, I had to help him. He was embarrassed and apologizing the whole time.”

“He’s going to need money,” I said. He could be hospitalized for months, and unless he had savings, he risked losing his apartment. I offered to pass a hat and spent the next week planning a gathering of his friends. That Saturday, three dozen people convened at my apartment with small sums of cash in envelopes, a little over $800 in total. Someone brought a bulky camcorder and we wished Brian a speedy recovery through the newest technology.

When the tape arrived in Chicago with the funds, Susan called to say he wouldn’t be watching it. “I guess he’s blind,” she said. “It happened so quickly. He was talking to his mother yesterday and said, ‘Norma’ — he calls her Norma — ‘Norma, would you turn on the light? We shouldn’t have to sit here in the dark.’ But of course, it was the middle of the day. Sunlight was streaming in. When they figured out what had happened, and that the blindness was irreversible, he was really scared. He said, ‘I’m a blind artist. What good is a blind artist?’ And she said, ‘Sculpture, honey. You could be a great sculptor.’ ”

His memorial service came a week later, at the Nazareth United Church of Christ, just blocks from where Brian had lived with Doug Gould, his nearly continuous partner since college. I arrived early, slipping into the pew beside Katrina Van Valkenburgh, my college girlfriend, midway between the entrance and the altar. Gould sat directly in front of us, alone at first, appearing to be stunned. He wore a speckled wool jacket and a whimsical bolo tie. His black hair, glossed tight over his temples, framed puffy and unfocused eyes.

That night Brian’s close friends gathered in an apartment nearby. Doug had gotten very drunk. Never much for talking, he was now muzzled as much by grief as by liquor, bumping his way to the kitchen for refill after refill. I learned from others that Brian had broken up with him a few months earlier — “probably the first sign of his brain infection,” someone surmised. Heartsick, Doug had tried to commit suicide. He checked himself into a hotel room with a plan involving pills, and when he survived the night, he returned to his parents’ home in rural Colorado, morose and aimless. Having raced back too late to bid Brian farewell in person added considerably to his burden.

After one especially unbalanced passage through the living room, I followed him into the kitchen to find him wrestling with a bottle of vodka. Grateful for my help, he didn’t notice that I filled his glass with tonic water instead.

“I didn’t talk to Norma,” he said, meaning Brian’s mother. His tongue was thick and slurry. “I couldn’t. She would hate me, blame me.”

I handed him his glass. “She would want to know what he meant to you,” I suggested.

“I guess I got it too. I told Brian I didn’t care.”

“You’ve taken the test?”

He shook his head. “But this,” he said, patting the back of his head. I reached over and put my palm against his Cherokee mane of black hair and encountered what felt like a large and moist scab. It encased most of his scalp. When I withdrew my hand and saw that it was red with blood, my heart pounded. I lurched for the kitchen sink and splashed myself with antibacterial soap, wringing my hands and scrutinizing my flesh for cuts and abrasions.

“Doug, what is that? You’re bleeding.”

He shrugged. The liquor had put a childish look on his face, sadness crossed with amazement. I noticed for the first time that the collar of his shirt was pink from his wound.

“Do you have a doctor?” I asked. He didn’t answer. “You need a good doctor, someone who understands AIDS. They know how to prevent the infections now. People are living with this. They can prevent death.” Tears filled his eyes, but he still said nothing.

“You have to come with me to New York,” I spontaneously added. “They’ve got way more experience there. I’ll get you to the right people. Don’t worry about money, I have a good job. I have room in my apartment. You can’t stay in Colorado.”

The invitation surprised me as much as it did him. But with Brian’s death, I felt a need to stop rummaging through the epidemic as a journalist, with the illusion of agency. I had been sitting on the sidelines for long enough.

“Let me take care of you,” I heard myself say.

Doug rocked unsteadily on his heels, then he kissed me drunkenly, which I took as his acceptance, though it may well have meant nothing. I mailed him a ticket, and a week later I met his flight at JFK and escorted him to the East Village, where we would figure out how to fight his illness together. I wasn’t surprised when our arrangement turned into an awkward romance. I felt the purest kind of love for him and what he had represented: our hopeful youth, our place in the world, life itself. I clung to him, and he allowed it — he needed it maybe as much as I did.

Doug was stunned by the scene in New York. Below 14th Street, KS lesions were as common as bug welts in the jungle. There was now a permanent line of wheelchairs outside the Village Nursing Home, where bony young men napped in the sun. The bars, which had been the teeming hub of gay society during his last visit, were now lifeless and ghostly places.

It was not easy to adjust to Doug’s presence in the apartment. With no job to distract him and laden with grief, he tended to wallow in daytime television, bales of marijuana, and frequent alcohol binges. In contrast to the garrulous and giggly young man I had known in college, he pushed people away, including those with whom he had been very close. “I don’t want people crying later,” he said. “I don’t want that responsibility.”

Winter 1991

By the time war in Iraq broke out, 100,000 Americans were dead from AIDS, nearly twice as many as had perished in Vietnam. In the East Village, someone in an apartment near Avenue C protested the war by turning an arena-strength loudspeaker out a window and playing a soundtrack of crisscrossing helicopters and gunships erupting in machine-gun fire. Night after night, the thunder of war reached deep into apartments like mine, where Doug was mostly immobile due to the pain in his feet. His spots wept continually, and several became inflamed by bacteria, requiring surgery that left disfiguring divots and welts here and there.

We took a vacation that winter: two weeks on the beach in Puerto Rico. Being on the beach without the infernal soundtracks of war was a relief, but the one time Doug removed his shirt, a 19-year-old on a nearby towel made note of all the marks on his flesh.

“Are those mosquito bites?” he asked, with genuine concern.

Doug glanced down at his marred chest and moved a finger from one spot to another, lesion to lump, virus to cancer, not sure how to answer. He opened his mouth to reply but no words came out.

We had been back in New York for a few weeks when I returned from work one night to find him in the stairwell halfway up to our apartment. He was covered in sweat. “I can’t make it,” he said, looking square in my eyes. “My feet are killing me. My lungs hurt.”

I took his canvas backpack and looped a hand around his waist to hoist him from one step to the next. “I’ll find us another place to live. A place with an elevator,” I said.

“No,” he snapped, steadying himself on the handrail. Grimacing, he took the next step himself, and the next. “Not yet.”

*This article appears in the November 14, 2016, issue of New York Magazine. © 2016 by David France