This week, Donald Trump announced that, because of the “spirit and the hope” he has already brought to the American economy, “the head people at Sprint” had called him to say “they’re going to be bringing 5,000 jobs back to the United States.” This declaration generated a fresh wave of positive headlines.

It’s a good story, and a good PR strategy, for Trump — but the reality is murkier.

The jobs Trump touted are a subset of the 50,000 U.S. jobs that the CEO of SoftBank — Sprint’s parent company — pledged to create in early December. And even that announcement wasn’t quite what it seemed.

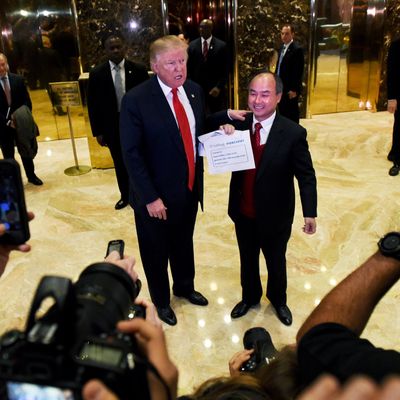

SoftBank CEO Masayoshi Son pledged to invest $50 billion into the U.S. economy following a meeting with Trump, which allowed the president-elect to claim the decision was the direct result of his election.

But Son had already announced plans to invest at least $25 billion into the U.S. economy back in October. It’s possible that Trump convinced Son to increase the size of his investment, but there’s no evidence of that.

Yet SoftBank willfully participated in the spectacle. And Sprint CEO Marcelo Claure tweeted out his company’s hiring plans Thursday, as though they were, in fact, news.

SoftBank is far from alone in opting to give the president-elect the headlines he wants. Per Politico:

A growing list of companies — including Dow Chemical, Carrier and IBM — have sought to give Trump the credit he seeks for job or investment announcements, hoping their concessions can win them seats at the table as Trump begins crafting policies in health care, education, financial services and technology … Some of the business pledges are recycled news, and others amount to little more than public-relations messaging that will be hard to track to see whether promises are realized — but analysts see it as an emerging way for investors and executives to stay on Trump’s good side.

Sprint has good reason to curry Trump’s favor: The company has long sought a merger with T-Mobile but found resistance from the Federal Communications Commission. Trump has the power to appoint a new audience for the company’s proposal. He’s also made sure to demonstrate the power his Twitter feed holds over the stock prices of companies; one imagines that any CEO might prefer to stay on his good side right now.

The federal government has considerable power to advantage some companies over others. A president willing to personally wield that power smacks of the brand of “picking winners and losers” that’s supposed to be reserved for authoritarian kleptocracies.

Trump can potentially keep up a continuous series of job-creation announcements — when it isn’t in recession, the American economy creates tens of thousands of jobs each month. His skill at telegraphing a thriving economy could prove as politically beneficial as an actually thriving one, for reasons political scientist Lee Drutman detailed in a recent essay on Trump’s Carrier deal:

To understand why Trump’s Carrier stunt succeeded, it’s worth turning to a 1964 political science classic, Murray Edelman’s The Symbolic Uses of Politics. The takeaway lesson is that in politics, clear symbolic actions are often more important than results (which are often ambiguous or unclear). As long as Trump defines his presidency through symbolic actions (like the Carrier deal), he could be very popular.

Edelman’s foundational point is that most people don’t pay close attention to the details of policy, and the news media does a poor job of covering the details (in large part because most people don’t care about the details). As a result, Edelman writes, “Politics is for most of us a passing parade of abstract symbols.” Knowing this, skillful presidents and other leaders can deceive mass publics through the careful use of symbols.

… It doesn’t matter whether problems are actually being solved. Most people can’t tell the difference, especially if the symbols tell them otherwise. It’s the appearance of forceful problem solving that matters. Like many classic problems of monitoring, it is far easier to judge the appearance of effort than the relationship between efforts and results. Hence, Edelman writes, “The public official who dramatizes his competence is eagerly accepted on his own terms.”