The CAPTCHA — that little test, often of recognizing letters, that you take in order to confirm to websites that you are a human, and not an automated program — is getting another upgrade. Last week, Google rolled out a new version of its reCAPTCHA product — one that, Google claims, won’t require you to do anything at all in order to tell if you’re machine or human.

Some quick history: the CAPTCHA (Completely Automated Public Turing test to tell Computers and Humans Apart) in its infancy was that box in which you had to copy a string of distorted characters — historically, one of few skills that humans are on average better at than computers. (For visually impaired users, audio clues are substituted as prompts.) The point of making users fill out CAPTCHAs is to prevent automated programs making requests over and over — to spam comments on a blog, for example. The term was coined by Luis von Ahn, Manuel Blum, Nicholas J. Hopper, and John Langford in 2003, but CAPTCHAs have existed in various formats since the mid-’90s, when the web became the domain of people and businesses other than techies. They’re a barrier between use and abuse.

The most popular CAPTCHA provider was reCAPTCHA, which Google purchased in 2009. Google filled its CAPTCHAs not with automatically generated nonsense, but with scanned images from its Books and Maps services — specifically, words and addresses that might have been mistranslated by automatic character-recognition programs. By solving those CAPTCHAs, users were building and feeding Google’s enormous database, translating visual clues like scanned books and photographs of houses into searchable, minable text. If you’ve ever searched inside a blurry old book in Google Books, you may have some anonymous person attempting to leave a comment on a blog to thank.

But as technology grows more advanced, so has computers’ capacity for reading text, and the text CAPTCHA as a tool has become less reliable for distinguishing between computers and humans. One development is the photograph CAPTCHA — the kind that asks you to “click all the squares with trees in them,” or something similar.

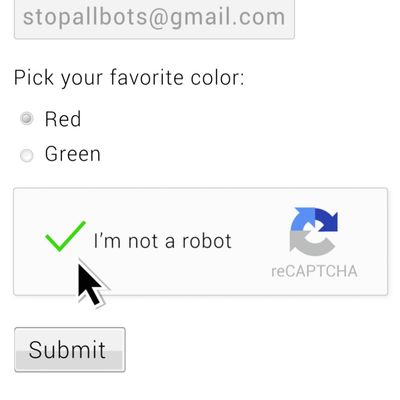

Google has gone in another direction. In 2014, Google rolled out the “No CAPTCHA reCAPTCHA,” which requires you to do nothing more complicated than check a box that says, “I’m not a robot.” On Monday, Google removed the checkbox. The new upgrade, called “Invisible reCAPTCHA,” functions without any clicks (really it just handles what was a one-click function automatically). Just wait a moment, and a page will determine whether or not you’re a human.

Google is not particularly forthcoming about how it makes this determination. In 2013, Google’s security blog described “actively considering the user’s entire engagement with the CAPTCHA—before, during and after they interact with it.” A paper presented at a 2016 Black Hat conference outlined tactics like installing cookies, examining what browser someone is using (this is known as a “user agent” and can be faked), and testing whether said browser can render certain elements on the page.

In other words, when you arrive at the website and mark the CAPTCHA checkbox (or don’t, with the Invisible reCAPTCHA), Google checks your behavior against its enormous set of other user behavior, and determines whether you act more like a human or a machine. The more people that use it, the larger the data set becomes, and the more the CAPTCHA system can learn.

How this whole thing works is not publicly explained in greater detail for understandable reasons (aside from it being very technical). If a tech company explains how a system works, it is also explaining how to circumvent that system. No doubt someone programming bots is already feeding them scripts that mimic human mouse and keyboard input.

Google’s own copy states that the system will “Help everyone, everywhere.” In this, it is correct: Who could object to a free, deployable system for sorting humans from computers, especially when it’s so easy to use? “Everyone” is indeed helped, especially Google. The system “makes positive use of this human effort by channeling the time spent solving CAPTCHAs into digitizing text, annotating images, and building machine learning datasets.” That translates to Google using this data to build impressive AI systems that they control entirely. Even when you’re not literally transcribing words for Google Books, or addresses for Google Maps, using reCAPTCHAs means helping build one of the world’s largest databases of human behavior — one that’s proprietary, closed, and wholly owned by Google.

(It’s important to note, however, that CAPTCHAs aren’t tracking individual users; they are — if I understand Google’s description correctly — taking anonymized data and adding it to a much larger set. Google’s developer terms allow it to retain content submitted through its API hooks, in order to improve said hooks, which is precisely how reCAPTCHA works. In this case, it’s whatever data signals that you are not an automated program. We’ve emailed Google to clarify what sorts of efforts CAPTCHA data is used for.)

If that’s not melodramatic enough for you, how’s this: We’ve made Google the largest — and maybe, eventually, the sole — arbiter of “human” and “bot” on the internet. And maybe that’s fine — maybe we’re suffering from such a plague of nonhuman internet users that we need a centralized system for determining which is which. And Google’s discretion regarding its filter isn’t a bad thing: If it tells the world how it works, it makes it easier to game. As with most things online, there is no easy solution. A centralized, black-box system makes the web efficient and accessible.

But we’ve already seen numerous times that private centralized technology — even in the interest of increasing stability and lowering user costs, and an abstract sense of the greater good — can have drastic consequences. If Amazon Web Services has a glitch, hundreds of thousands of websites experience service interruptions, as they did a couple weeks ago. Facebook as a web portal has completely reshaped how people consume media, arguably for the worse. A Cloudflare bug affecting millions of sites left sensitive data accessible to the public. Letting one company or service dominate a function of the web is never a good idea. Google’s CAPTCHA system is a large-scale operation for harvesting data to use however it sees fit. Is it nefarious? Hardly. But will it pose challenges in the long term? Definitely.