In a press conference defending his health-care plan yesterday, Paul Ryan rattled off the same buzzwords he has been repeating for years. “It means more choices and competition so that you can buy the plan that you need and that you can afford,” he said. The plan creates “a better, patient-centered system,” and “gives people the freedom to buy the plan they want and can afford.”

If you don’t know exactly what all these terms mean — choice, competition, freedom, patient-centered — that’s fine by him. It’s better than fine, actually. It’s the point. All these terms are meant to complicate the real choice his plan presents, which is a very simple one: more versus less.

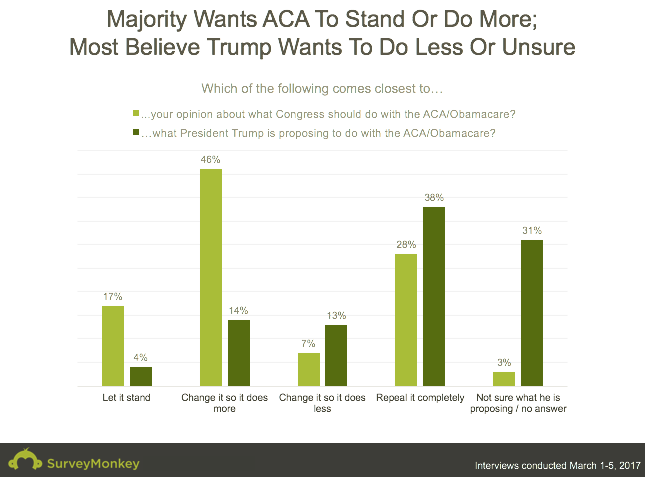

Obamacare was designed in an intensely budget-conscious atmosphere, with the requirement that it reduce the deficit, which put severe pressure on its costs. The result is that, while it gives some 20 million people access to insurance, much of that insurance is fairly stingy. To the extent that people don’t like Obamacare, it is mostly because they think the law does not cover enough. This recent poll is illuminating:

Those who want to keep the law or have it do more outnumber those who want to eliminate it or have it do less by almost two to one. The most popular position by far is to change Obamacare to make it do more — commanding 46 percent. Changing Obamacare to make it do less gets just 7 percent. That public-opinion landscape explains why Republicans have relentlessly attacked the law for its skimpiness and promised more generous coverage.

Yet that latter position, the one preferred by just 7 percent, is what Trumpcare does. Right-wing dissidents have dismissed Ryan’s bill as “Obamacare Lite.” There’s some truth to this. Conservatives do have ideas for radically redesigning the health-care system in a way that relies on the power of patients as educated consumers to drive down costs. The terms Ryan threw around, like “patient-centered” and “competition,” are normally associated with those policies. As Ross Douthat points out, very few of these ideas made it into Ryan’s bill. That’s because implementing those ideas correctly would either cost money or alienate enormous constituencies. (The biggest idea conservatives have, cutting or eliminating the tax deduction for employer-sponsored insurance, was left out because it’s politically radioactive.)

And so what emerged from the frantic, tax-cut-deadline-driven process was a bill that’s essentially Obamacare, but less of it. Obamacare created two vehicles to cover people who couldn’t get insurance. It expanded Medicaid to cover the poorest of the uninsured, and those who made more money received tax credits they could use to buy insurance on new state-based exchanges.

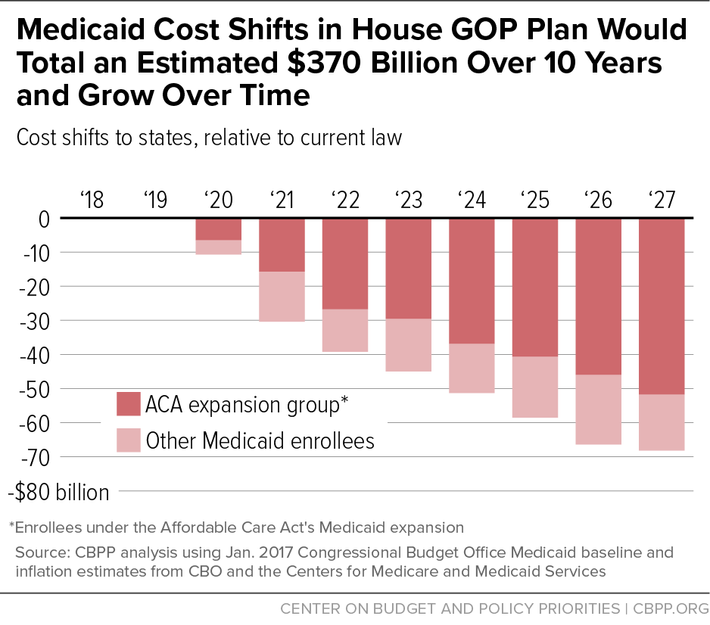

Trumpcare cuts funding for Medicaid by $370 billion over a decade, and the cuts are heavily backloaded:

And it reduces funding for subsidies on the exchanges by $2,409 per person by 2020. To be sure, that is an aggregate figure. There are huge variations. Young people, the affluent, and customers in low-cost markets would do better, and some of them actually get more support from Trumpcare than they do from Obamacare. On the other hand, older, poorer customers in high-cost markets (like rural areas, especially) would get absolutely hammered. Abby Goodnough and Reed Abelson report on a few of them. In North Carolina, a 55-year-old would see her tax credit cut from $8,688 to $3,500. A 60-year-old would see his family’s tax credit reduced from $25,164 to $11,500.

Those cuts would make any decent insurance plan not remotely affordable. And there is no design reform, no theory, that could make up for the gap between those peoples’ resources and the cost of their care. (The cost of modern medical care is beyond the resources available to them.) You’re either going to give them enough money to access medical treatment, or you’re not. Paul Ryan prefers not because he has a deep philosophical aversion to the kinds of income redistribution required to cover the uninsured. But rather than make that unpopular case, he obscures it with a lot of vague lingo about “choice” and “competition.”

The most naked and revealing moment of Ryan’s press conference came when he was asked about why his plan provides a huge tax cut for the rich. You can watch his response, ten minutes in. Ryan scoffs and makes a dismissive hand gesture, like he’s been presented with an utterly frivolous objection. Then Ryan says, “Read the bill! Go to readthebill.gop!” and moves on to next question while he and his lieutenants share forced laughter at the absurd query.

It is of course incontrovertibly true that Ryan’s bill provides a big tax cut for the rich. It’s a $600 billion tax cut, almost all of which would accrue to the very rich. His tax cut is a major reason why his plan provides fewer resources to cover the poor and sick. He believes that feature is so unpopular and objectionable he literally cannot even acknowledge its existence. It is emblematic of his entire approach. Ryan’s strategy is to pass his plan into law without ever admitting its central objective.