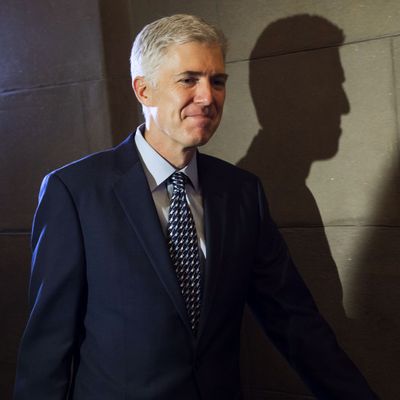

“A trucker was stranded on the side of the road, late at night, in cold weather, and his trailer brakes were stuck,” wrote appeals court judge Neil Gorsuch, last August, in a dissenting opinion that is apt to come up at his confirmation hearings next week for the open seat on the U.S. Supreme Court.

“He called his company for help and someone there gave him two options,” Gorsuch continued. “He could drag the trailer carrying the company’s goods to its destination (an illegal and maybe sarcastically offered option). Or, he could sit and wait for help to arrive (a legal if unpleasant option). The trucker chose None of the Above, deciding instead to unhook the trailer and drive his truck to a gas station.”

About a week later, in January 2009, the employer, TransAm Trucking, fired the driver for insubordination. In January 2013, an administrative law judge ruled that the trucker’s termination had been illegal, under a federal law that protects employees who “refuse to operate” vehicles under unsafe conditions. In November 2014 that ruling was unanimously upheld by a three-member administrative review board of the U.S. Department of Labor and then, last August, by Gorsuch’s two colleagues on a three-judge panel of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit.

Gorsuch parted ways with them because, as he explained, the trucker could have simply waited in his tractor-trailer. The problem, then, wasn’t that the driver had “refused to operate” the truck in an unsafe way, Gorsuch explained, but rather that he had operated the truck, and had done so in a way his employer had forbidden.

“It might be fair to ask whether TransAm’s decision was a wise or kind one,” Gorsuch continued. “But it’s not our job to answer questions like that … It is our job and work enough for the day to apply the law Congress did pass, not to imagine and enforce one it might have but didn’t.”

Laconic, sharp-edged, concise, and arch, the writing style has grown familiar. It is that of many conservative judges who call themselves “textualists” or, when interpreting constitutional provisions, “originalists” — jurists who believe they have found a more objective basis for decision making than their liberal colleagues, whom they deride for trying to interpret the law to achieve just results, a goal these conservative judges deem hopelessly subjective.

Yet there are other adjectives for Gorsuch’s dissent. Obtuse, callous, elitist, and cruel are contenders. He displays a manner of thinking that might disappoint — if not shock — many of the white, working-class voters who turned out for Trump in November. For what follows are the facts of this case as found by the administrative law judge, which all the appeals judges, including Gorsuch, were legally bound to accept.

On January 14, 2009, trucker Alphonse Maddin picked up a load of frozen meat in Nebraska that was to be delivered to several locations, in Wisconsin and Michigan. At about 11 p.m., while traveling through Illinois in subzero temperatures, his engine began “sputtering.” The fuel gauge had dipped below empty and he couldn’t find a gas station. (It was later determined that TransAm had misidentified the gas station’s location on the map it had provided Maddin.) Maddin pulled off the road, contacted TransAm, and was informed that the driver who had been scheduled to “switch out” with him couldn’t do so, so he’d have to continue the trek himself.

Maddin restarted the truck but discovered that the trailer’s brakes had frozen, due to the frigid temperatures. He called TransAm’s “Road Assist” unit at 11:16 p.m., and was told to wait there for a repairman.

When the truck was being driven, it used one heating system, but when the motor was off, the driver had to rely on a bunk heater run by an auxiliary power unit. Maddin’s auxiliary power unit, however, had stopped working earlier in the trip. So Maddin waited in the unheated truck. After about an hour, he fell asleep.

At 1:18 am — nearly two hours after first calling Road Assist — Maddin was awakened by a cell-phone call from his cousin. The cousin became alarmed by how Maddin sounded; he seemed to be shivering, and his speech was slurred. Maddin straightened up in the cab and noticed that his skin was “crackling” from the cold, his torso was numb, and he couldn’t feel his feet, according to the administrative review board ruling. Maddin hung up with his cousin and called TransAm’s Road Assist unit again. He was told to “hang in there.”

According to the review board opinion, Maddin “tried to follow this suggestion but became fearful of losing his feet, dying, and never seeing his family again.” After another half-hour with no relief, he called his TransAm supervisor, reporting his physical symptoms which, by then, also included trouble breathing. Maddin explained that he wanted to unhook the trailer from the cab and drive to a gas station. The supervisor ordered him, however, according to the review board decision, “to either drag the trailer with its frozen brakes or stay where he was,” warning that the company could be fined if Maddin left the trailer unattended.

Shortly after the call ended, at 2:05 a.m., Maddin detached the trailer and set off looking for the gas station, which he eventually found. Then, at 2:19 a.m. — three hours after originally reporting the frozen-brake issue — he was called by the repair truck operator, who had finally arrived. Maddin drove back to the trailer, where repairs to the brakes were completed at 3:20 a.m. A week later, Maddin was fired for having disobeyed the orders of his supervisor.

Under the federal Surface Transportation Assistance Act, an employee can’t be fired if he “refuses to operate a vehicle … because the employee has a reasonable apprehension of serious injury to the employee or the public because of the vehicle’s hazardous safety or security condition.” The review board found Maddin protected by this provision. Gorsuch’s colleagues on the Tenth Circuit concluded that the board’s interpretation was reasonable, given that the purpose of the law, explicitly laid out in its preamble, was to “promote the safe operation of commercial motor vehicles” and “minimize dangers to the health of operators of commercial vehicles.”

Gorsuch ridiculed his colleagues’ reasoning, and especially their appeal to the statute’s stated purpose of advancing health and safety.

“When the statute is plain, it simply isn’t our business to appeal to legislative intentions,” he wrote. “After all, what under the sun, at least at some level of generality, doesn’t relate to health and safety?”

Gorsuch’s dissent in TransAm Trucking has drawn some unadmiring scrutiny in recent weeks. An Associated Press article last month described the opinion as one that appears to “defy common sense and fairness,” while the progressive Constitutional Accountability Center asserted in a white paper issued Friday that Gorsuch’s “crabbed interpretation” of the law was “anything but a fair reading of a statute enacted to protect worker and public safety.”

Realistically, nothing seems likely to derail Gorsuch’s nomination at this point. He has the votes and, truth be told, he is qualified for the post in terms of credentials and experience.

But Judge Gorsuch’s rulings do highlight the stark disconnect between Trump’s populist campaign rhetoric and the gated-community elitism of his first High Court nominee.

It is in flesh-and-blood details of court cases like Maddin’s that the rubber of Trump’s vaunted populism will meet the road. The question is how long it will take Trump’s constituents to notice, and to hold him accountable.