Much of the Republican factional infighting over the new American Health Care Act involves the proposal’s impact on the Medicaid program. And that’s appropriate: For all the discussion of Obamacare’s exchanges for purchasing individual health-insurance policies, a majority of the roughly 20 million uninsured Americans who obtained coverage under the Affordable Care Act did so through the Medicaid program, which ACA expanded to cover working poor people without children or disabilities. Even though the Supreme Court made this Medicaid expansion optional, 31 states ultimately accepted it, some lured by very generous federal financial inducements that let them try out conservative policy experiments on the Medicaid population. So it’s worth some effort to understand how the new proposal affects the Medicaid expansion and the underlying program, and how that affects the politics of the repeal-and-replace effort.

Ever since Obamacare became law, Republican politicians have been struggling with ways to reverse the expansion and pursue a long-standing goal of limiting federal responsibility for the low-income population served by Medicaid. However, they have been doing so over the objections of 13 Republican-governed states that chose to participate in ACA’s Medicaid expansion. The GOP’s new American Health Care Act appears to incorporate a decision to offer states short-term Medicaid money in exchange for sharp, permanent cuts down the road. Like most of the AHCA’s provisions, its treatment of Medicaid may fall between two stools and satisfy no one.

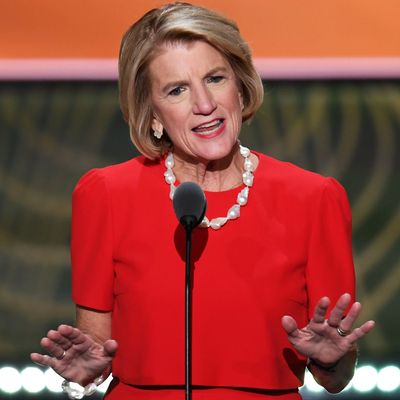

Four GOP senators (Shelly Moore Capito of West Virginia, Cory Gardner of Colorado, Lisa Murkowski of Alaska, and Rob Portman of Ohio) representing Medicaid-expanding states were among the loudest voices complaining about the leaked February 10 draft of the House GOP’s Obamacare replacement legislation, which would have simply killed the expansion after 2020. That language would have left the expansion states with a choice of abandoning millions of beneficiaries or covering them at the much lower pre-expansion match rate. So the actual bill tweaked the transition to let expansion states continue to get the “super-match” for new beneficiaries who signed up by the end of 2019 — in effect a phase-down of the expansion instead of a phase-out (though in reality the tendency of Medicaid beneficiaries to cycle quickly and repeatedly in and out of coverage could mean a faster phase-down than one might imagine).

But the bill retains a “Medicaid reform” feature that conservatives were promoting long before Obamacare was created: a “per capita cap” on how much the federal government will pay the states for each beneficiary. Unlike a “block grant,” which just limits the total amount states receive from Washington to cover all Medicaid beneficiaries, a cap will let states cover more people, but not expand the range of benefits or pay doctors and other providers at a higher rate. Because of vast differences between the states on benefit and reimbursement rates, there are huge variances in per capita expenditures between the states. In 2016, Georgia spent $4,245 per beneficiary, while Massachusetts spent $11,091. These inequities would likely be frozen in amber by a per capita cap.

Over time, the AHCA is designed to ratchet down federal Medicaid spending as the generous federal inducements the expansion offered fade away, and states decide to do more for fewer people, or less for more people. Based on applying the AHCA formula to actual recent costs, the liberal Center for Budget and Policy Priorities estimates the per capita cap would shift $370 billion in costs from the federal government to the states over ten years. And the shift could get much, much larger if the arbitrary allotments to the states created by the cap are lowered by future Congresses. Indeed, many conservatives have long viewed Medicaid “reforms” like a per capita cap as a way station to dumping the whole mess on the states — or better yet, private charities and individuals themselves —once and for all.

So the AHCA formula essentially exchanges short-term generosity to the states for long-term reforms that will hammer them. That should buy off current Republican governors while making conservatives happy, right? Not necessarily. GOP governors (e.g., Nevada’s Brian Sandoval) are already beginning to complain the phase-down of funding for the Medicaid expansion will still throw a lot of people out of coverage, soon if not immediately. And nearly all the governors are alarmed by the absence of language in AHCA giving them the flexibility to use reduced funds as they wish to serve the eligible population.

Meanwhile, some conservatives — especially from non-expansion states —are angry that the Medicaid expansion is being accommodated at all, and according to some accounts Donald Trump is listening to them. And other commentators are noting that the interaction of the AHCA’s Medicaid and private insurance provisions will actually produce immediate pressure on the states to expand Medicaid to avoid a big coverage loss from inadequate purchasing subsidies. As influential conservative health-policy expert Avik Roy argues, the AHCA’s tax credits for individuals to buy health insurance are so small that the working poor will have a strong incentive to stay in Medicaid instead of entering the individual market, while the states will have a strong incentive to keep Medicaid as large as they can to avoid a big spike in the ranks of the uninsured. And that will infuriate those many conservatives who view big, permanent, and immediate changes to Medicaid as the shriveled booby prize they receive for having to abandon (or so it seems right now) their more avaricious dreams of “entitlement reform” in the Trump era.

As in other aspects of health-care policy, on Medicaid the AHCA tries unsuccessfully to placate the various Republican factions. And any further “tweaks” are almost certain to increase one faction’s fury even if the lower another’s — particularly in the Senate, where losing just three of 52 Republicans will likely prove fatal to the entire enterprise.