Later this month, after 12 years without executing an inmate, the state of Arkansas will go on an unprecedented killing spree when it puts seven men to death in a span of 11 days. The rapid pace of the executions is being driven by the looming expiration of a drug used in the lethal cocktail administered to inmates.

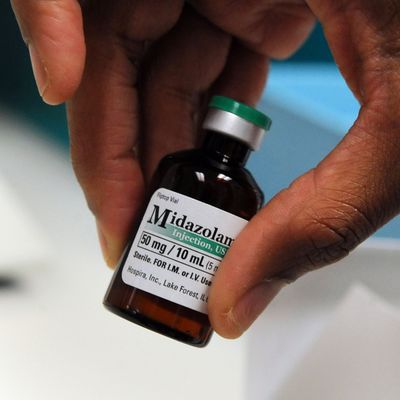

The state’s supply of the controversial sedative midazolam expires at the end of April. In February, Governor Asa Hutchinson scheduled the seven executions (along with another that has since been blocked) to ensure they take place before the drug expires. Executions will take place April 17, 20, 24, and 27, with three out of those four days seeing back-to-back lethal injections.

“In order to fulfill my duty as Governor, which is to carry out the lawful sentence imposed by a jury, it is necessary to schedule the executions prior to the expiration of that drug,” he said in a statement to NPR.

The packed schedule is drawing criticism from civil-liberties advocates, former corrections officers, and even Hutchinson himself. “It’s not my choice,” he recently said of the tight execution schedule. “I would love to have those extended over a period of multiple months and years, but that’s not the circumstances that I find myself in.”

Advocates for the rights of the inmates have pointed out that executions scheduled so close together have a higher likelihood of mistake. That’s why the practice of conducting two on the same day was largely abandoned decades ago. A lawsuit calling the schedule unconstitutional filed by the inmates says, “Just one mistake at any point can have disastrous consequences.”

The people administering the executions could suffer too. Allen Ault, who previously oversaw executions in Georgia, recently told NPR that cramming the executions into so few days risks magnifying the psychological effects on those filling the syringes. “I don’t know anybody that has been involved who had a conscience that was not dramatically affected by it,” Ault said. “And we’ve had several correctional officials who later became alcoholics. Some committed suicide. Many of them were diagnosed with posttraumatic stress disorder, including myself.”

All seven of the inmates scheduled to die this month are men. Three are white, four are black, all have been on death row since before 2000 and all were convicted of murder. But Harvard Law School’s Fair Punishment Project makes the case that several of the men do not belong on death row. Some suffer from mental illness or intellectual disability, while all of the inmates received legal representation that “falls short of any reasonable standard of effectiveness.” That includes one lawyer who was drunk in court.