Uber’s recent string of bad press — high-level executives heading for the hills, #DeleteUber, allegations of rampant discrimination — has started to include not just the, um, dubious things Uber has done of late, but also some potentially shady parts of its past. According to a new piece from Mike Isaac at the New York Times over the weekend, back in 2015 the company allegedly used a secret code to tag and track iPhones even after phone owners had deleted the app. The tactic was reportedly used to deter people — namely new drivers in China — who were downloading, deleting, and re-downloading the app to sign up with multiple email addresses and capitalize (and re-capitalize) on new-driver incentives. (Uber ultimately failed in China, but at this point it was heavily investing in an attempt to conquer the nation’s ride-hailing market.)

When an iPhone user wipes their phone clean, it’s supposed to be just that: clean. According to Apple policy, doing so should leave a phone with no traces or record of its previous owners. To get around this, the New York Times reports, Uber added a “fingerprint” to each iPhone it was monitoring, or a tiny piece of code that allowed the company to track the devices even after they were wiped clean by their owners. In order to avoid getting in trouble with Apple, Uber geo-fenced the company in a way that would hide the secret fingerprint code to anyone inside the area. (This feels similar to another tactic Uber was recently discovered to have employed where a secret software called Greyball was used to tag and track law-enforcement officials who might hurt the company’s business.)

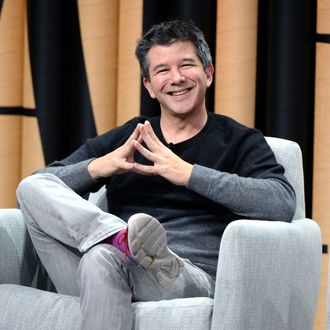

Apple eventually got wise. Tim Cook reportedly called Kalanick in for a meeting in Cupertino: “So, I’ve heard you’ve been breaking some of our rules.” Post-meeting Kalanick stopped the fingerprinting process, with a source telling the Times he was “shaken” by the “scolding.”

Update, April, 24, 2017, at 11 a.m.: Uber provided Select All with the following statement regarding the New York Times report.

We absolutely do not track individual users or their location if they’ve deleted the app. As the New York Times story notes towards the very end, this is a typical way to prevent fraudsters from loading Uber onto a stolen phone, putting in a stolen credit card, taking an expensive ride and then wiping the phone — over and over again. Similar techniques are also used for detecting and blocking suspicious logins to protect our users’ accounts. Being able to recognize known bad actors when they try to get back onto our network is an important security measure for both Uber and our users.