For about half a year now, progressives have been squabbling about how to explain the tragic events of November 8. These internecine arguments have sometimes centered on a pair of related questions:

1. Was Clinton’s defeat caused primarily by a failure of persuasion (Obama voters flipping to Trump) or one of mobilization (Democratic voters staying home, while “missing white voters” flocked to the GOP standard-bearer)?

2. To the extent that Trump did win over some white Obama voters, did he do so by activating their racial resentment, or their longing for economic change (a.k.a. “economic anxiety”)?

Debate over these questions was rarely characterized by a spirit of coolheaded empiricism. And not without reason — each answer seemed pregnant with profound ideological and political implications.

Some progressives saw explanations that centered the economic concerns of Obama-Trump voters as attempts to (once again) minimize the role that white racial animus plays in our politics. And they worried that this allergy to confronting the power of racism would lead the Democratic Party to court a romanticized white working class, instead of working to bring the millions of disengaged, left-leaning, young, black, and Latino voters into the electorate.

Others on the left viewed explanations that painted Obama-Trump voters as irrelevant — or, else, as motivated exclusively by racism — as unfounded apologies for Hillary Clinton’s failure to offer a compelling economic message. And they worried that this allergy to confronting the inadequacy of center-left economics would lead the Democratic Party to court socially moderate, fiscally conservative suburban whites, instead of building the cross-racial, working-class movement necessary to bring about truly progressive change.

These ideological investments and anxieties — along with myriad others — lent fights over the left’s dueling autopsies much of their intensity. But what made the arguments truly tenacious was the fact that everyone’s preferred autopsy was (at least a little) right.

On Monday, a group of Democratic strategists released the findings of a months-long investigation into Hillary Clinton’s political demise. Here’s what they concluded, per McClatchy:

Obama-Trump voters … effectively accounted for more than two-thirds of the reason Clinton lost, according to Matt Canter, a senior vice president of the Democratic political firm Global Strategy Group. In his group’s analysis, about 70 percent of Clinton’s failure to reach Obama’s vote total in 2012 was because she lost these voters … His firm’s conclusion is shared broadly by other Democrats who have examined the data, including senior members of Clinton’s campaign and officials at the Democratic data and analytics firm Catalist.

That same day, the Democratic super-PAC Priorities USA published the results of its focus groups and polls of Obama-Trump voters. The Washington Post’s Greg Sargent rounded up group’s most striking findings:

•50 percent of Obama-Trump voters said their incomes are falling behind the cost of living, and another 31 percent said their incomes are merely keeping pace with the cost of living.

•A sizable chunk of Obama-Trump voters — 30 percent — said their vote for Trump was more a vote against Clinton than a vote for Trump. Remember, these voters backed Obama four years earlier.

•42 percent of Obama-Trump voters said congressional Democrats’ economic policies will favor the wealthy, vs. only 21 percent of them who said the same about Trump. (Forty percent say that about congressional Republicans.) A total of 77 percent of Obama-Trump voters said Trump’s policies will favor some mix of all other classes (middle class, poor, all equally), while a total of 58 percent said that about congressional Democrats.

So: It was the Obama-Trump voters, in the Rust Belt, with the economic anxiety. Disaffected workers in deindustrialized America, who believed that Trump was a genuine populist — and sympathized with Bernie Sanders’s critique of the Democratic Party — cost Clinton the election.

But then, so did insufficient Democratic turnout. Here’s McClatchy again:

Democrats are quick to acknowledge that even if voters switching allegiance had been Clinton’s biggest problem, in such a close election she still could have defeated Trump with better turnout. She could have won, for instance, if African-American turnout in Michigan and Florida matched 2012 levels.

And so did white America’s discomfort with the anti-racist, multicultural vision of our country that the Clinton campaign embraced. Analyses of postelection survey data have revealed that in 2016, the American electorate was more sharply polarized along lines of racial tolerance than it had been at any time in recent memory — and that “individuals with high levels of racial resentment were more likely to switch from Obama to Trump.”

And Clinton’s defeat was also, probably, caused by James Comey, as she herself claimed today; and by the candidate’s own fatal combination of oratorical weakness and a (fair or unfair) reputation for coziness with malign special interests; and sexism; and her campaign’s distaste for deep canvassing; and its neglect of the Rust Belt.

When an election is decided by 80,000 votes, a plausible case can be made for the decisive impact of a wide variety of individual factors. And there is some evidence to support virtually every popular narrative for Clinton’s defeat.

That said, there appears to be a growing consensus that Obama-Trump voters were a much bigger problem for Clinton than superior Republican turnout: Global Strategy Group’s research actually found that Clinton won a majority of new voters in Ohio, even as she lost the state by eight points.

But when one focuses on the fact that roughly 40 percent of eligible voters didn’t turn out in 2012 and 2016 — and that this enormous, nonvoting population looks demographically and ideologically favorable for Democrats — putting outreach to Obama-Trump voters above efforts to expand the electorate can seem myopic. Particularly when one considers the large communities of unregistered Latino voters in Texas’s cities — and all the Electoral College problems they could one day solve for Team Blue.

Happily, the imperatives of persuasion and mobilization are in no way mutually exclusive. Priorities USA’s focus groups with “drop-off voters” — those who pulled the lever for Obama in 2012 and then stayed at home in 2016 — suggest they have much in common with “soft” Obama-Trump voters. Specifically, many in both groups feel that their incomes aren’t keeping pace with the cost of living, and oppose cuts to Social Security, Medicare, and Obamacare.

Tying Trump to the GOP’s regressive agenda — and stoking the class resentments of white workers in the Midwest — does not preclude efforts to increase black and Hispanic turnout in the Sun Belt. Pushing for state legislatures to expand automatic voter registration and expand early voting does not undermine attempts to craft an economic platform and message that will resonate in Kenosha County.

And, at least theoretically, you can do these things while also using Team Blue’s commitment to rationality and professionalism to make inroads with the moderate, college-educated white voters who find themselves discomfited by the know-nothing ethno-nationalists and far-right theocrats who have consumed America’s “center-right” party.

Of course, there will be some tension between these efforts. A sharp class message pitched at cautious Obama-Trump voters could alienate parts of “Panera land.” And energizing nonvoting blacks and Latinos may require bold stances on immigration and policing that could theoretically alienate otherwise reachable whites from Youngstown to the Atlanta suburbs. If nothing else, the party’s finite resources will force it to prioritize courting some voters over others, a fact that this year’s special elections have already highlighted.

But a glance across the aisle shows that it is possible for a major party to make few ideological compromises on the federal level, while also cultivating disparate regional identities to remain competitive in hostile states. In recent years, even as their national party became evermore radically reactionary, Republican candidates won gubernatorial races in Massachusetts, Maryland, and Illinois; last fall, the GOP put a far-right demagogue in the White House — and a Republican in Vermont’s governor’s mansion.

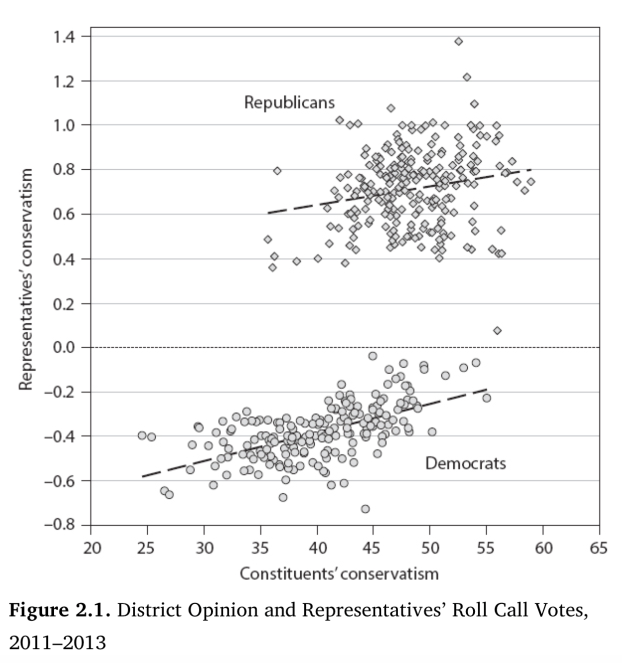

Further, once in office, elected representatives often display a significant degree of ideological independence from the leanings of their constituents: As political scientists Christopher Achen and Larry Bartels note in Democracy for Realists, when Republican House candidates win moderate districts, they frequently vote like conservative Republicans, and the same is true of House Democrats.

Nor is there an inescapable correlation between the wealth of an area and its tolerance for redistributive economic policy. California’s 17th district is among the wealthiest in the country, encompassing parts of Silicon Valley — and its congressman is pushing for a $1 trillion expansion of the Earned Income Tax Credit, a proposal that left-wing activists are cheering as the first step toward a universal basic income.

All of which is to say: The left’s competing explanations for Clinton’s defeat — and prescriptions for the path forward — aren’t as mutually exclusive as many suggest.

To be sure, the members of the motley crew marooned together on the left side of America’s political aisle still have plenty of sound reasons to claw at each other’s eyes. On the normative questions of what constitutes a “progressive” platform on education, financial reform, health care, national security, jobs, workers’ rights, immigration, policing, and many other issues, there are real divides in blue America’s tent. There are inherent conflicts between the Democratic Party’s corporate wing and its activist base. And these fights have real stakes, no matter how much some in the party like to insist otherwise.

But we’d all be well-served by resisting the temptation to project the certainty of our moral convictions onto empirical questions of political reality. Doing so makes us susceptible to ignoring inconvenient but potentially useful insights, like the fact that Trump really did dramatically outperform the typical Republican candidate with low-income voters — or that social democratic polices have not been a surefire prophylactic against white nativist backlash in other Western nations.

Progressives should relentlessly defend their visions of what should be; but maintain an open mind about what is, and what has been.