If we make it through 2020 without a civilization-threatening international calamity, a decent share of the credit will go to the men Donald Trump likes to call “my generals.” As one of his first national-security appointments, Trump nominated James Mattis, a retired four-star Marine, to serve as secretary of Defense, and has since handed over much of American foreign policy to Mattis and the uniformed military leadership at his side. They are everything our commander-in-chief is not: steady-handed, competent and decent professionals, truthful and generally cogent communicators. When Trump says or does something unsettling — such as today’s bombastic scolding of our NATO allies for not paying their share — they can walk it back after the fact. In a crisis, they will be singularly positioned to save the republic.

But the sheer scale of expectation should also be cause for concern. It is not just that we may be asking too much of the generals, given the dysfunction and venality around them. By depending so much on the influence of those in (or recently out of) uniform, short-term salvation could come at considerable long-term cost — for American foreign policy, and for the military itself.

The “axis of adults” in Trump’s national-security cabinet was supposed to extend beyond the Pentagon. In addition to Mattis, there was Secretary of Homeland Security John Kelly, another recently retired four-star, and National Security Adviser H.R. McMaster, an active-duty Army three-star who took over after the downfall of Mike Flynn (himself a retired general, though of less distinction). Secretary of State Rex Tillerson had a decade of experience running a global company with 75,000 employees.

But Tillerson was quickly disqualified by his own taciturn ineptitude. Kelly turned out to be troublingly enthusiastic about Trump’s anti-immigration agenda, proposing to separate asylum-seeking mothers from their children and chiding lawmakers for daring to criticize his agency; a hot mic caught his toadyish joking with Trump about using a saber on reporters. And McMaster, renowned for both iconoclastic battlefield command and an acclaimed book on the Vietnam War, has proved much less adept when it comes to restraining or managing his boss. (That he is still on active duty, and thus in a military chain of command with Trump at the top, makes his situation especially delicate.) Last week, McMaster was sent to undercut stories about Trump’s disclosure of Israeli intelligence to the Russian foreign minister — only to be contradicted the next day by Trump himself. And in exchange for destroying his reputation, McMaster is not earning Trump’s gratitude for being so supine, according to recent reports, but Trump’s ire for not being supine enough.

That leaves Mattis as the last “adult” standing. Known as both tough and cerebral, a “warrior monk” who goes home to bachelor’s quarters to read history, he retired in 2013 after overseeing military operations in the Middle East as head of Central Command. After he was nominated as secretary of Defense, Congress waived the seven-year wait required before an officer can take the job (a rule designed to preserve civilian control over the military and overridden just once before, in 1950). Mattis, in turn, assured Democrats he would offer “frank advice” in “every circumstance.”

Trump himself — who avoided the draft because of a “temporary” problem with his feet — seems most interested in Mattis’s supposed barracks nickname (“Mad Dog”), no-nonsense speaking style, and “central casting” square jaw and steely visage. He is Trump’s “favorite,” joke White House officials. “I love the generals,” says Trump. Whatever the reason, it is usually lucky he does. He dropped lusty campaign-trail calls to reinstate water-boarding after Mattis told him torture doesn’t work. Iraq was omitted from the rewritten Muslim ban, thanks to reminders that American and Iraqi troops are together battling ISIS in Mosul. Military leaders helped puncture the idea of a grand bargain with Vladimir Putin. Mattis has flown around the world telling allies that the United States can still be counted on, an attempt to clean up messes of Trump’s making. “We’re not in Iraq to seize anybody’s oil,” he said on his first visit to Baghdad, contradicting Trump’s lusty campaign-trail calls to do just that. The only thing as compelling to Trump as a man in uniform is a man in a $10,000 suit.

As with so much about this administration, there is a parallel to the Watergate era. With Nixon increasingly prone to boozy, paranoid rages, top officials concluded that he should sometimes be taken neither literally nor seriously. Secretary of Defense James Schlesinger told officers to get a second opinion before carrying out presidential orders. National Security Adviser Henry Kissinger instructed them to disregard “our drunken friend” until he sobered up. This time around, it falls to Mattis and military leaders to check apocalyptic impulses emanating from the Oval Office.

Yet their influence can go only so far. The military can execute a missile strike on Syria with efficient professionalism, but that doesn’t make up for the lack of a broader strategy. Mattis can block especially noxious personnel choices, but his alternative picks have been repeatedly rejected by the White House. At any moment, the best-laid plans can be upended by a predawn tweet or the preferences of a 30-something real-estate heir. While Trump may listen to his generals when they’re with him, he is just as likely to take cues from a lecture by Xi or a segment on Fox. And the role that hopeful outsiders have foisted upon Mattis and the military is one that runs counter to principles drilled into them over decades. They are as aware as anyone that it is not a healthy sign for a democracy, or for civil-military relations, when salvation comes in uniform.

Nor is it comforting that the military has found a compensating advantage in this newfound freedom of action. Officers bristled at micromanagement by the previous White House — a reflection of the risk aversion at the heart of Obama’s foreign policy (“don’t do stupid shit”). Mattis himself left his last post early because the administration found him too hawkish on Iran.

Now, without close Washington oversight and carefully enforced rules of engagement, a commander in Afghanistan can call in “the mother of all bombs” without asking permission, or order a raid in Somalia, whatever the risk of U.S. casualties. The Pentagon can increase troop levels in Iraq and Syria with no sign-off from the president — a major abdication by the commander-in-chief. Drone operators can launch missiles without careful deliberation in the Situation Room about targeting and casualties. Last week, American planes bombed Iranian proxy forces in southern Syria. “What I do is, I authorize my military,” Trump has explained. “We have given them total authorization, and that is what they are doing.” Military leaders, with their personal awareness of the human toll, are not typically the most ardent advocates for war. Still, Trump’s hands-off approach means heightened risks, greater danger for American troops, more civilian deaths (and consequent anti-American backlash) — all to uncertain strategic ends.

The book that helped make McMaster’s reputation is worth reconsidering here. When McMaster was appointed, his study of military leaders’ failures in the early years of the Vietnam War, Dereliction of Duty, was held up as a parable of the need to speak truth to power. But in fact, in McMaster’s telling, the “truth” that officers were failing to forcefully deliver to their civilian bosses was not that America should get out of Vietnam, but that it needed to do more. They found Lyndon Johnson too cautious rather than too hawkish — a not especially soothing fable at present.

A more recent lesson is more pertinent: the dangers of an overly militarized foreign policy. Since 9/11, money and prestige have flowed to the Pentagon, and other tools of American power have struggled to keep up. (I saw it serving in the Obama administration State Department: Generals travel on their own planes, trailed by large staffs, with cash to spend, while their civilian equals fly coach, carry their own bags, and have scant resources — foreign officials draw obvious conclusions about where the power lies.) The imbalance will be even more pronounced now, given the unfilled civilian jobs and weakened agencies. Mattis has summarized the consequences as well as anyone: “If you don’t fund the State Department fully, then I need to buy more ammunition.” What will Mattis need if the State Department is not just underfunded but eviscerated, as Trump appears intent on doing with no apparent pushback from Tillerson?

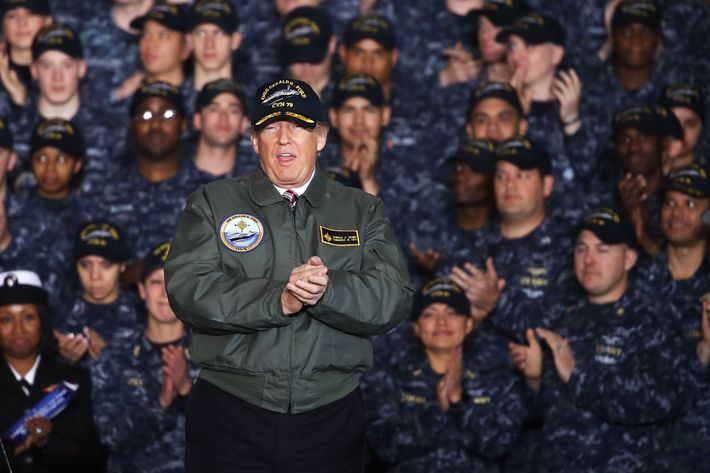

This week, the White House proposed cutting support for diplomacy and development by a third and adding $52 billion to the Pentagon’s budget. (That same amount was the entire Obama-era annual allocation for the State Department and U.S. Agency for International Development.) After all, diplomats don’t have much use as political props, whereas appearances with American troops serve as opportunities for impromptu partisan rallies for Trump, where he can order men and women in uniform to cheer his cause. No matter that he is violating a foundational aspect of American democracy — an apolitical military — in the process.

Yet adulation could easily falter. Trump’s standard practice is to make grand, incoherent promises and then find someone, anyone, to blame for failure. In foreign policy, the gap between extravagant goals and insufficient means is where trouble starts, and Trump has already demonstrated his inclination to throw the military under the bus at the first sign of it. “They explained what they wanted to do, the generals, who are very respected,” he said after a raid in Yemen went awry and left a Navy SEAL dead. “And they lost Ryan.” Military leaders, conditioned by training and ethos to accept responsibility, are unlikely to push back. “I’ll take the hit for it,” said an admiral after a confusingly worded military press release about an aircraft carrier headed toward North Korea was magnified by White House incompetence into a strategic fiasco.

“Americans like our military partly because it is good at its job,” Mattis wrote with a co-author last year. What happens when the commander-in-chief starts regularly blaming it for his own lapses?

Today, the military is the most respected institution in America, one of very few that still get much respect at all. Seventy-three percent of Americans say they have a “great deal” or “quite a lot” of confidence in it — compared to 41 percent for organized religion, 39 percent for the medical system, 20 percent for newspapers, and 9 percent for Congress. In the Trump era, outsize expectations of what officers, in and out of uniform, can do, along with their outsize role in carrying out policies unmoored from strategy and impelled by cable-news quips and narcissism, will test that confidence more than it has been tested anytime since Vietnam. The generals may save us, but they may not be able to save themselves.