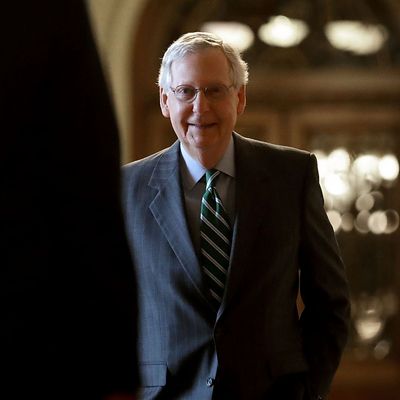

The House-passed health-care bill is an astonishingly unpopular piece of legislation, which in some polls has failed to reach even 20 percent approval. Even many of the Republicans who support it publicly have expressed reservations; a number of House supporters said they merely hoped to keep the process alive and move the bill to the Senate, and Trump himself privately called the bill “mean.” And the Senate version is equally draconian. Its tax credits will do more to help the economically vulnerable than the House bill, but its Medicaid cuts are even deeper. So how does Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell think he can pass it through his chamber?

If the bill passes — which, at this early moment in the lightning-fast process, seems quite likely — it will be because McConnell took advantage of the anchoring effect. The starting point is a brutal, cruel piece of legislation with massively unpopular features. (The public overwhelmingly opposes Medicaid cuts, which are the bill’s most pronounced effect.) It will reportedly draw public opposition from at least some holdout Republicans. At that point, the holdouts will be able to wrest relatively small concessions from McConnell.

These concessions will have outsized political impact. They will be new and newsy, and reporters will be drawn from the old story — the outlines of the bill — toward the newer developments. The major coverage of the bill will likely focus on changes in the proposed law that make coverage more affordable. The overall law will still make coverage less affordable overall, but that large fact will remain in the background.

Social scientists call this this “anchoring effect.” People tend to have hazy ideas about what is sensible or fair, and have a cognitive bias toward “anchoring” their sense of the correct answer by whatever number is presented to them initially. In one typical experiment, people in job interviews who start by mentioning absurdly high sums, even as an obvious joke, could get higher offers.

The Senators who negotiate those small changes will attract outsized attention, and their public imprint will disproportionately shape coverage. This effect might wear off over a longer period of time, but it can well succeed in the compressed time frame McConnell intends to permit.

That is how a House bill that seemed to be dead was quickly resurrected. Representative Tom MacArthur proposed an amendment, and his amendment, however tiny, represented movement. The movement, not the overall contours of the bill, dominated both news coverage and the vulnerable members’ thinking. In the end, the revised version of the House bill reduced the number of insured Americans by 23 million rather than the original 24 million. It was the 1 million fewer, not the 23 million remaining, that mattered most when it counted.

The Senate bill, like the House bill, would represent the largest setback in public health and low-income support in the history of American government. That will remain true regardless of what concessions any “moderate” member might obtain. Any Senator who negotiates within its established parameters is accepting its monstrous moral calculus.