Ever since Democrats fell short of their 2016 goal of taking back control of the U.S. House, there’s been talk about, and even a formal (if unsuccessful) leadership challenge aimed at achieving, a leadership change in the House Democratic Caucus. And after Democrats failed to win any of the four GOP House seats where special elections were held this year, there was renewed talk about Nancy Pelosi stepping down as House Democratic Leader. The negative buzz became particularly loud after the party’s biggest special-election hope, Georgia’s Jon Ossoff, suffered a disappointing loss, in the wake of Republicans running many millions of dollars of ads linking the candidate to Pelosi.

As my colleague Eric Levitz pointed out, the attack ads against Ossoff associated him with demon-figures a lot more potent and remote than Pelosi. One last-minute ad even tried to link the Democrat with unnamed elements of “the violent left” who were allegedly cheering the Scalise shooting.

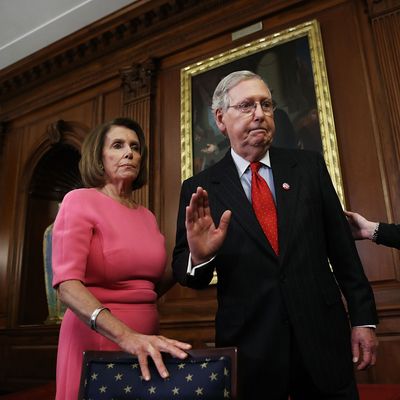

But the fact remains that Pelosi is a much bigger target for Republicans than Paul Ryan or Mitch McConnell appears to be for Democrats. Part of the problem may simply be that she happens to represent a jurisdiction with rich negative symbolism (dating back at least to the attacks on “San Francisco Democrats” in 1984 after the Donkey Party held its convention in the City by the Bay) for the conservatives who are mostly the target for anti-Pelosi ads. You cannot quite imagine Democrats running ads mocking Paul Ryan’s Wisconsin or Mitch McConnell’s Kentucky in this manner. And sexism could most definitely be a factor as well.

Anti-Pelosi agitation among Democrats sometimes gets into perceived problems with her image and with the party’s performance since 2010, and sometimes edges over into ideology. As Matt Yglesias notes, the ideological signals replacing Pelosi might send are not exactly consistent with the direction of the Democratic caucus generally:

Ever since her 2002 whip race against Hoyer, her rivals for leadership have been white men who are positioned at least somewhat to her right ideologically, operating in the context of a House Democratic caucus that is increasingly diverse and increasingly progressive.

But arguments about what Nancy Pelosi has and has not done, or what she does and does not represent, often miss her basic problem: She’s been a party leader for a very long time in an era when both parties in Congress are chronically unpopular.

Pelosi has been leader for more than 16 years. Mitch McConnell, who seems to have been in leadership for an eternity, has actually just been leader for just over ten years. Paul Ryan has been Speaker for just three years, and Chuck Schumer has been the Democratic leader for less than a year.

All these politicians have underwater approval/disapproval ratios, but the depths to which they have sunk is in reverse order to seniority. According to one recent tabulation, Pelosi’s ratio is 29/53; McConnell’s is 30/47; Ryan’s is 36/49; and Schumer’s is 33/42.

So the most compelling case for a change in leadership has nothing to do with Pelosi’s actual performance or perceptions of her ideology: She’s just been there too long.

Pelosi is the longest-serving Democratic House leader since Sam Rayburn, who has a House office building named after him. Unlike House Republicans, who have since 1995 maintained term limits for committee chairs and ranking committee members, House Democrats have never instituted the practice of limiting any sort of leadership positions (mostly because they felt it would disproportionately affect minority members who were just beginning to ascend in the seniority system).

But with respect to their top position, they might want to adopt informal, if not formal, term limits. Pelosi has served two different stints in the minority, and if Democrats win back the House in 2018, she will have held the Speaker’s gavel twice. That is more than enough for anybody. If the objection is that the first woman Speaker should stay in her position as long as she likes, it should be noted there are now enough women in the House to avoid the necessity of another male Speaker for decades to come. Pelosi’s position in history is secure. That is not true of her party’s position in Congress.