Three and a half months after an engineer named Susan Fowler published a blog post detailing her experience of sexual harassment as an employee of Uber, the company has at last begun to detail the results of multiple investigations into its infamous workplace culture. At Uber’s weekly all-hands meeting on Tuesday, lawyers from an external law firm told the company’s 12,000-plus employees that it had received 215 claims of misconduct — sexual harassment, discrimination, retaliation, bullying — and fired 20 people as a result. Three dozen others had been required to undergo counseling or given a final warning. More than 50 cases were still pending. On Twitter, a female Uber engineer responded to the news by writing that she was “[f]eeling 20 assholes lighter.” She quickly had second thoughts and deleted her tweet.

While none of the female Uber employees I spoke to for my piece on the company’s various crises had experienced anything close to Fowler’s horror stories, almost all reported a variety of incidents and interactions that made the company a difficult place to work. (Uber employees I reached out to who had spoken positively about the company’s culture all referred me to its press office.) One engineer told me that her boss, a six-foot-five man, responded to her criticism of an idea of his in a one-on-one meeting by standing up, getting red in the face, and declaring, “I’m the manager, and you should care about whether I agree or not.”

One theme that comes up routinely in my conversations with people across the company is the fact that there are many distinct Ubers, each with its own culture and issues. While Uber has claimed, for various regulatory reasons, that it is a technology company, it is by any honest estimation a transportation provider that resembles a modern Greyhound as much as it does Facebook. The vast majority of its employees — setting aside its hundreds of thousands of drivers, who are the company’s public face, but who it insists are not employees — are not programmers; they work in operations, marketing, public policy, communications, finance, and the numerous other nontechnical positions required to address the various challenges involved in running a global taxi business.

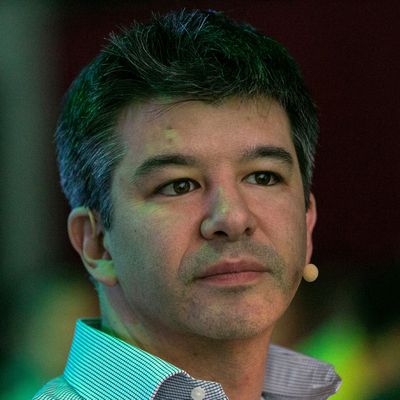

In those departments, nearly half of Uber’s employees are women, according to the company’s recent diversity report; at one point, the heads of legal, human resources, communications and public policy, and North American operations were all women. And while sexism and sexual harassment know no departmental barriers, and occurred throughout the company — a report from the Intercept earlier this spring found that many female Uber drivers had experienced harassment on the job and found themselves without adequate recourse — many employees told me that the major workplace issues in the company’s nontechnical departments were less overt incidents of sexual harassment than a general culture of aggression, insensitivity, and growth at any cost that trickled down from the company’s CEO Travis Kalanick and his inner circle. The values Kalanick codified as the company’s guiding principles — “toe-stepping,” “always be hustlin’” — may not have explicitly enabled sexual harassment, but they did little to discourage the 33 people among the 215 claims who were accused of bullying. “People say the culture’s really bro-y, which it is, but people think that ‘bro’ automatically means male,” one male former employee told me. “The ‘lady bros’ at Uber are just as bad.” One woman told me that her female boss called her into a meeting, and casually had her feet kicked up on her desk as she told the woman that she could either be reassigned to a new city or find a new job.

Of all the many distinct Ubers, however, the engineering department might have the most hostile — and most recalcitrant — culture. Just 15 percent of Uber’s technical staff are women; most of the men are young, many are in their first jobs. According to a number of former employees, stereotypes often hold true, and many of the male programmers at Uber seemed to have little experience in how to interact appropriately with the opposite sex. I was taken aback when I asked one former senior Uber engineer about Fowler’s blog post, to which he responded by dismissing her claims. “I don’t think Susan Fowler’s claims were even mostly true,” he said — acknowledging that they may have been “partly true,” but declining to explain how or why he had reason to doubt them. (According to Recode, the manager she accused of harassment was fired before the investigation.) He was willing to admit that Fowler had likely experienced sexism at Uber, but defended the company largely on the grounds that it was no worse than anywhere else.

Setting aside the considerable evidence that Uber was in fact a demonstrably less friendly place for women than other major tech companies, the engineer was right that tech remains a particularly difficult field for women. While the number of female engineers at Uber is shockingly low, it is not out of line with the rest of the tech world. According to a lawsuit brought earlier this year by a former employee at the augmented-reality company Magic Leap, sexism was rampant, as when a member of its IT staff answered a female employee’s question by saying, “Yeah, women always have trouble with computers.” (The case was settled out of court last month.) At Google, some 15,000 employees subscribe to an employee-run newsletter that details incidents of sexual harassment and sexism, among other concerns. According to Bloomberg, the newsletter is titled, “Yes, at Google,” making the point that these types of incidents occur even at a place viewed as overwhelmingly welcoming to its employees.

Will anything change at Uber? Twenty firings certainly send a message, but the fact that it took an outside law firm to sort out the problem was a fairly damning assessment of the company’s human-resources department, which has never quite kept up with its shocking growth thus far. (If Uber adds as many employees this year as it did last year, it will have built a workforce roughly as large as Facebook’s in half the time.) While many people at Uber told me that it seemed to be business as usual at the company, a roughly equal number said Kalanick was making a sincere effort to change both his own leadership style and the culture. Uber’s most prominent recent hires — an artificial-intelligence expert to bolster its flailing self-driving effort; a marketing executive from Apple; a respected management guru from the Harvard Business School who helped the school become more welcoming to female students — have all been women, all with stellar credentials. Whether their respective hirings will make a real impact or are merely a means of dampening the blow of yesterday’s report, and another report on the company’s culture that is expected to be released next week, remains to be seen.

As important as what Uber learns from this will be what Silicon Valley learns, which may be very little. One venture capitalist told me that the Valley tended to see the missteps and flaws in other start-ups and presume that they were unique to that company. “There’s very little soul-searching,” he said. Several people I spoke with compared Uber to GitHub, a start-up that similarly became the subject of a highly public investigation into workplace culture in 2014, after a female engineer complained of a hostile environment. In the aftermath of the GitHub investigation, one of its founders resigned. Three years on, a female engineer told me that GitHub’s reputation among women had more or less normalized, but as the experience of many women at Uber has shown, the GitHub controversy seemed to have done little to change the situation for women in the Valley more broadly. Even Uber’s critics point out that the workplace concerns have had little effect on the company’s growth. Unless its bottom line takes a hit, it’s unlikely that tech’s next aspiring unicorn will see much reason to act any differently.