A generation ago, “neoliberalism” was the chosen label of a handful of moderately liberal opinion journalists, centered around Charles Peters, then-editor of the Washington Monthly. Some neoliberals started calling traditional liberals “paleoliberals.” The magazine most closely associated with traditional liberal thinking was The American Prospect, which gave me my first job out of college.

When I started there, I asked one of the editors, Paul Starr, about the still-roiling schism between the neos and the paleos. (I never felt comfortable with either label.) Starr told me he disdained the term because it was “an attempt to win an argument by using an epithet.” What he meant — and I think he was right — was that “paleoliberal” was not a self-identification any of its adherents used, but a term of disparagement. The neolibs were claiming to own the future and consigning their adversaries to the past.

The neoliberalism of the 1980s and 1990s has faded into memory, as its adherents failed to settle on a coherent set of principles other than a general posture of counterintuitive skepticism. (Peters’s new ideological manifesto, We Do Our Part, only mentions neoliberalism once.) But the term has been used to mean different things at different times, and it has returned to American political discourse with a vengeance. Then, as now, it is an attempt to win an argument with an epithet. Only this time, it is neoliberal that is the term of abuse.

And the term neoliberal doesn’t mean a faction of liberals. It now refers to liberals generally, and it is applied by their left-wing critics. The word is now ubiquitous, popping up in almost any socialist polemic against the Democratic Party or the center-left. Obama’s presidency? It was “the last gasp of neoliberalism.” Why did Hillary Clinton lose? It was her neoliberalism. Paul Krugman and Joseph Stiglitz? Neoliberals both.

The Baffler’s Chris Lehmann dismisses an Atlantic story on the Democrats, which touts Elizabeth Warren as a model for the party’s future, as just more neoliberal tripe. “In the world of neoliberal consensus, it’s a simple taken-for-granted axiom that senators — the lead fundraisers and media figures in both major parties — call the shots, and should be entrusted with charting an electoral comeback,” writes Lehmann. “All the reliable notes of arm’s-length cultural puzzlement are struck soundly here, from the putative identity-politics-class-politics divide on the left to the neoliberal wonk class’s painfully absent common touch.” Obviously, the authentic way to demonstrate a common touch is to throw around the term neoliberal as frequently as possible. Try it if you ever need to strike up a conversation with some strangers in a bowling alley in Toledo.

Neoliberalism is held to be the source of all the ills suffered by the Democratic Party and progressive politics over four decades, up to and (especially) including the rise of Donald Trump. The “neoliberal” accusation is a synecdoche for the American left’s renewed offensive against the center-left and a touchstone in the struggle to define progressivism after Barack Obama.

++

The ubiquitous epithet is intended to separate its target — liberals — from the values they claim to espouse. By relabeling self-identified liberals as “neoliberals,” their critics on the left accuse them of betraying the historic liberal cause.

Indeed, the appearance of the “neoliberal” epithet in a polemic almost axiomatically implies a broader historical critique that has been repeated many, many times.

Its basic claim is that, from the New Deal through the Great Society, the Democratic Party espoused a set of values defined by, or at the very least consistent with, social democracy or socialism. Then, starting in the 1970s, a coterie of neoliberal elites hijacked the party and redirected its course toward a brand of social liberalism targeted to elites and hostile to the interests of the poor and the working class.

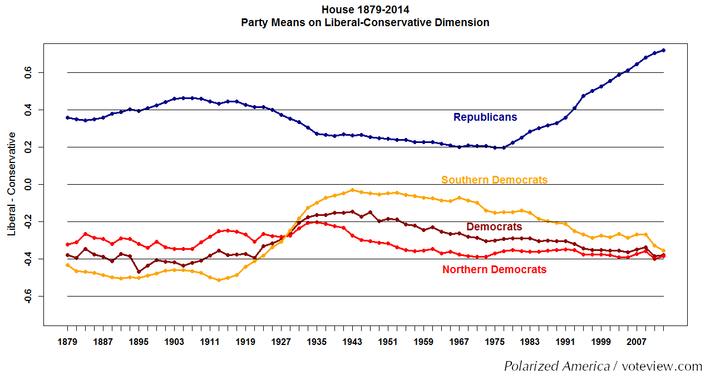

The first and most obvious problem with this version of history is that there is little reason to believe the Democratic Party has actually moved right on economic issues. The most commonly used measure of party ideology, developed by Keith Poole and Howard Rosenthal, has tracked the positions of the two parties’ elected members over decades. Here is how they have evolved on issues of the government’s role in the economy:

This chart indicates that Democrats have not moved right since the New Deal era at all. Indeed, the party has moved somewhat to the left, largely because its conservative Southern wing has disappeared.

Now, the Poole-Rosenthal measure does not end the discussion. No metric can perfectly measure something as inherently abstract as a public philosophy. One obvious limit of this measure is its value over long periods of time, when issue sets change in ways that make comparisons difficult. The Poole-Rosenthal graph has special difficulty comparing the Democratic Party before and after the New Deal. But it does raise the question of why the Democrats’ supposed U-turn away from social democracy does not appear anywhere in the data.

Any remotely close look at the historical record, as opposed to a romanticized memory of uncompromised populists of yore, yields the same conclusion as the numbers. The idea that the Democratic Party used to stand for undiluted economic populism in its New Deal heyday is characteristic of the nostalgia to which the party faithful are prone — no present-day politician can ever live up to the imagined greatness of the statesmen of past.

In reality, the Democratic Party had essentially the same fraught relationship with the left during its supposed golden New Deal era that it does today. The left dismissed the Great Society as “corporate liberalism,” a phrase that connoted in the 1960s almost exactly what “neoliberalism” does today. The distrust ran both ways. Lyndon Johnson supported domestic budget cuts after the disastrous 1966 midterm elections, to the disappointment of liberals who already loathed the Vietnam War. “What’s the difference between a cannibal and a liberal?” Johnson joked during his presidency. “A cannibal doesn’t eat his friends.”

Nor was the “corporate liberal” critique exactly wrong. Today the left holds up Medicare as a shining example of health-care policy designed by social democrats, before it was corrupted by the modern Obama-era party and its suborning of the insurance industry. In reality, powerful financial interests deeply influenced the design of Medicare. The law’s sponsors had hoped to achieve universal health insurance, but retreated from that ambitious goal in large part because insurers wanted to keep non-elderly customers. (They were happy to pawn the oldster market off on Uncle Sam.) Likewise, the law defanged opposition by the powerful American Medical Association by agreeing to fee-for-service rules that wound up massively enriching doctors and hospitals. And the creation of Medicaid as a separate program for the poor relegated them to a shabbier and more politically vulnerable category.

John F. Kennedy was a cautious trimmer whose domestic agenda included cutting the top income-tax rate 20 points. “Politically, he tended to court the opposition and ignore his friends,” wrote one columnist. “His motto might have been: no enemies to the right.” Harry Truman was “more fearful of labor and labor’s political power than of anything else,” charged one dismayed liberal. Progressive Party candidate Henry Wallace, who inspired a passionate mass movement on the left quite similar to today’s Bernie-or-busters, lambasted Truman as a tool of Wall Street.

The tradition of progressives flaying Democratic presidents for betraying the spirit of the New Deal goes all the way back to the New Deal itself. Even the sainted Franklin Roosevelt vacillated between expansionary fiscal policy and austerity, and between attacking corporate power and encouraging monopoly. The cause of liberalizing international trade, which left-wing critics have treated as a corporate-friendly Clinton innovation, is one Roosevelt not only supported consistently but basically invented. Roosevelt’s 1936 speech denouncing wealthy interests is widely repeated today by nostalgic progressives, but it marked a brief and rare populist turn. Mostly he strove for class balance.

Historian William Leuchtenburg describes the president’s “determination to serve as a balance wheel between management and labor … Despite the radical character of the 1934 elections, Roosevelt was still striving to hold together a coalition of all interests, and, despite rebuffs from businessmen and the conservative press, he was still seeking earnestly to hold business support.” For much of his presidency, “The New Republic raked FDR on a regular basis,” admits a collection published on the magazine’s centennial.

The Democratic Party has evolved over the last half-century, as any party does over a long period of time. But the basic ideological cast of its economic policy has not changed dramatically since the New Deal. American liberals have always had some room for markets in their program. Democrats, accordingly, have never been a left-wing, labor-dominated socialist party. (Union membership peaked in 1955, two decades before the party’s supposed neoliberal turn, and has declined steadily since.) They have mediated between business and labor, supporting expanded state power episodically rather than dogmatically. The widespread notion that “neoliberals” have captured the modern Democratic party and broken from its historic mission plays upon nostalgia for a bygone era, when the real thing was messier and more compromised than the sanitized historical memory.

Progressives are correct in their belief that something has changed for the worse in American politics. Larger forces in American life have stalled the seemingly unstoppable progressive momentum of the postwar period. Rising international competition made business owners more ruthless, civil rights spawned a 40-year white backlash against government, and anti-government extremists captured the Republican Party, destroying the bipartisan basis for progressive legislation that had once allowed Eisenhower to expand Social Security and Nixon to create the Environmental Protection Agency.

All this forced Democrats more frequently into a defensive posture. Bill Clinton tried but failed to create universal health coverage, eked out modest tax increases on the rich, and fought off the “Republican revolution” by defending Medicare, Medicaid, education, and the environment, crown jewels of the Great Society.

Barack Obama’s far more sweeping reforms still could not win any support from a radicalized opposition. It is seductive to attribute these frustrations to the tactical mistakes or devious betrayals of party leaders. But it is the political climate that has grown more hostile to Democratic Party economic liberalism. The party’s ideological orientation has barely changed.

++

Given that the self-proclaimed neoliberal movement of the ’80s never really took hold, and has long since passed into obscurity, why have the long-standing grievances of the left against the mainstream Democratic Party attached themselves to the “neoliberal” label only recently?

“Neoliberalism” has a second meaning, unrelated to the small faction of Washington Monthly alumni. (Or, at least, the neoliberals of that generation had no awareness of it.) In the international context, “neoliberal” means capitalist, as distinguished from socialist. That meaning has rarely had much application in American politics, because liberals and conservatives both believe (to starkly differing degrees) in capitalism. If “neoliberal” simply describes a belief in some role for market forces, then it is literally true that liberals and conservatives are both “neoliberal.”

It is strange, though, to apply a single term to opposing combatants in America’s increasingly bitter partisan struggle. If the party that created Obamacare and the party trying to destroy it, the party of higher taxes on the rich and the party of lower, the party of tighter pollution limits and the party of allowing oil drillers to write regulations are each “neoliberal,” then neoliberalism is of limited use in describing American politics.

The sudden ubiquity of the term in American politics — at least among left-wing elites — owes itself to two new developments. First, the Bernie Sanders campaign has inspired a new movement to remake the Democratic Party as a social-democratic labor party. Left-wing activists need a label for their opponents.

Conservatives have spent decades turning “liberal” into a smear meaning “left-wing radical,” giving it limited value as a term of opprobrium. (In terms of self-identification, liberals constitute the left wing of the Democratic base, with moderates and conservatives constituting a slightly larger right wing.) In practical terms, people who think of themselves as “liberal” form the constituency the Bernie insurgents need to attract.

Second, the widely publicized influence of neoconservatives within the Bush administration changed the connotation of “neo.” Whereas the prefix had once softened the term it modified — the neoconservatives were once seen as the intellectually evolved wing of the right, in contrast to the Buchananite knuckle-draggers — by the end of Bush’s term, it became an intensifier. A neoconservative was a conservative, but an even scarier one.

And so the term neoliberal frames the political debate in a way that perfectly suits the messaging needs of left-wing critics of liberalism. The uselessness of “neoliberalism” as an analytic tool is the very thing that makes it useful as a factional messaging device for the left. The “neoliberalism” rubric implicates the Democratic Party in the rightward drift of American politics that has in reality been caused by the Republican Party’s growing radicalism. It yokes the two parties together into a capitalist Establishment, against which socialism offers the only clear alternative. Obscuring the large gulf between Newt Gingrich and Bill Clinton, Paul Ryan and Barack Obama, is a feature of the term.

A recent New York Times op-ed by Bhaskar Sunkara, editor of the Marxian journal Jacobin, lays the tactic unusually bare. Sunkara argues that the West faces three possible alternatives.

One is nationalist authoritarianism of the sort advanced by Trump, Hungary’s Jobbik Party, France’s National Front, etc. The second is Singapore, an authoritarian technocracy that he calls “the unacknowledged destination of the neoliberal center’s train.” And his third option is “avowedly socialist leaders like Mr. Sanders and Jean-Luc Mélenchon in France.”

Sunkara omits from his choices any liberal mixed economy of the kind that exists in Western Europe and Scandinavia and that American liberals would like to build here. He is very clear that this final option, the one he advocates, is “not the social democracy of François Hollande, but that of the early days of the Second International.” He excludes the more moderate brand of social democracy from the menu because he believes too many people would choose it. The whole trick is to bracket the center-left together with the right as “neoliberal,” and then force progressives to choose between that and socialism.

The socialist left has an argument to make against liberalism. It reveals a certain lack of confidence in that argument when it tries to win it with an epithet.