Former White House chief strategist and chairman of Breitbart News Stephen Bannon is at an interesting point in his career. Most visibly, he is presenting himself as the ringleader in an effort to purge (or at least discipline) Republican senators deemed insufficiently loyal to Donald Trump and his movement. At the same time, Bannon is also trying to distance himself from some of the unsavory associates and associations that once shared a lot of bandwidth with himself, Breitbart, and Trump.

According to BuzzFeed’s Joseph Bernstein, Bannon has declared his former Breitbart underling and alt-right agent provocateur Milo Yiannopoulos “dead to me” after reading Bernstein’s own recent exposé of Milo’s modus operandi and connections. Other readers may differ, but I thought the most shocking thing in that exposé was how much Bannon and his wealthy friends the Mercers seemed to be micromanaging Yiannopoulos as a way to mobilize and channel the sinister energy of the alt-right on behalf of Trump and Trumpism. Perhaps Bannon is just cutting his losses and moving on.

But beyond jettisoning Milo, Bannon is also putting behind him the increasingly tainted brand “alt-right,” as are an awful lot of Trumpite agitators who don’t want to be identified with outright white supremacists like Richard Spencer. In his latest piece, Bernstein applies their favorite alternative brand, “new right,” to Bannon as well.

It’s an interesting choice: “New right,” like, say the “New Democrats” (echoed by Tony Blair’s “New Labour”) of the Clinton era, is a brand that sounds cool and relevant without conveying any information about the content of the belief system involved.

But “new right” is hardly a new term in American politics. And in fact, the original new right of the 1970s had a lot in common with today’s new-new right. With leaders like direct-mail wizard Richard Viguerie, anti-feminist Phyllis Schlafly, grassroots organizer Howard Phillips, and the great ring-wing institution builder Paul Weyrich (founder of both the Heritage Foundation and ALEC), the new right was self-consciously populist, nationalist, focused on cultural and racial resentments, and exceedingly hostile to the Republican Establishment of its day. Before Reagan’s 1976 and 1980 campaigns gave them a route to power within the GOP, the new right flirted with creating a new “Producer’s Party” that would form a coalition with George Wallace–style right-wing ex-Democratic “populists.” In 1975, here’s how National Review publisher William Rusher described the new right’s rationale, as reflecting:

[a] new economic division [that] pits the producers—businessmen, manufacturers, hard-hats, blue-collar workers and farmers—against the new and powerful class of nonproducers comprised of a liberal verbalist elite (the dominant media, the major foundations and research institutions, the educational establishments, the federal and state bureaucracies) and a semipermanent welfare constituency, all co-existing happily in a state of mutually sustaining symbiosis.

If it sounds familiar, it should: It’s pretty much the same worldview as that which possesses the Trump movement, though the old group’s distinctive anti-communism obviously doesn’t carry over, and the new group’s focus on immigration didn’t make sense in the 1970s. There’s even a similar leadership dynamic: the original new right revered Ronald Reagan as the pol who led them to the Promised Land. But deep down, they only trusted true believers like Jesse Helms, their real leader and the man who kept pressure up on the Gipper’s right flank. Similarly, Trump is his movement’s Daddy, but the serious thinking and discipline are in the hands of people like Bannon. Maybe later one of the insurgent pols he is encouraging to run roughshod over an Establishment Republican will head up the new right in Congress.

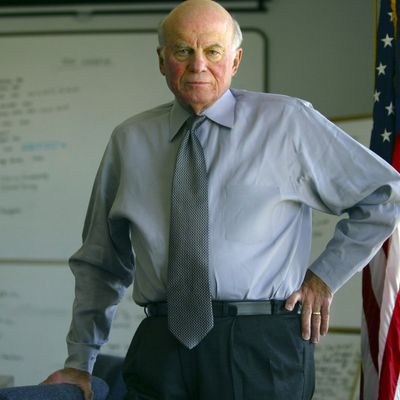

Aside from all the similarities, there is a living link between the new right of the 1970s and its new incarnation today: Richard Viguerie. The author of a triumphal 1980 manifesto, The New Right: We’re Ready to Lead (the introduction was written by Jerry Falwell, father of Trump’s conservative evangelical chieftain Jerry Jr.), Viguerie once pursued the presidential nomination of George Wallace’s American Independent Party and was very close to Jesse Helms (who called the senator “our beloved leader”). Now in his 80s, Viguerie is still vigorously active, and very much a backer of Donald Trump. He recently joined several younger conservative leaders in penning a combative letter demanding that Mitch McConnell and his entire Senate leadership team step down — pretty much the same line Steve Bannon has been pursuing.

So if “new right” is what we are going to call the splinter elements of the alt-right who don’t want to be called racist, let’s recognize that there’s nothing especially “new” about it all. It’s a group of right-wing activists singing pretty much the same old song of cultural resentment and economic “producerism,” and supporting a lot of Republicans who only care about lowering marginal tax rates and killing regulations.