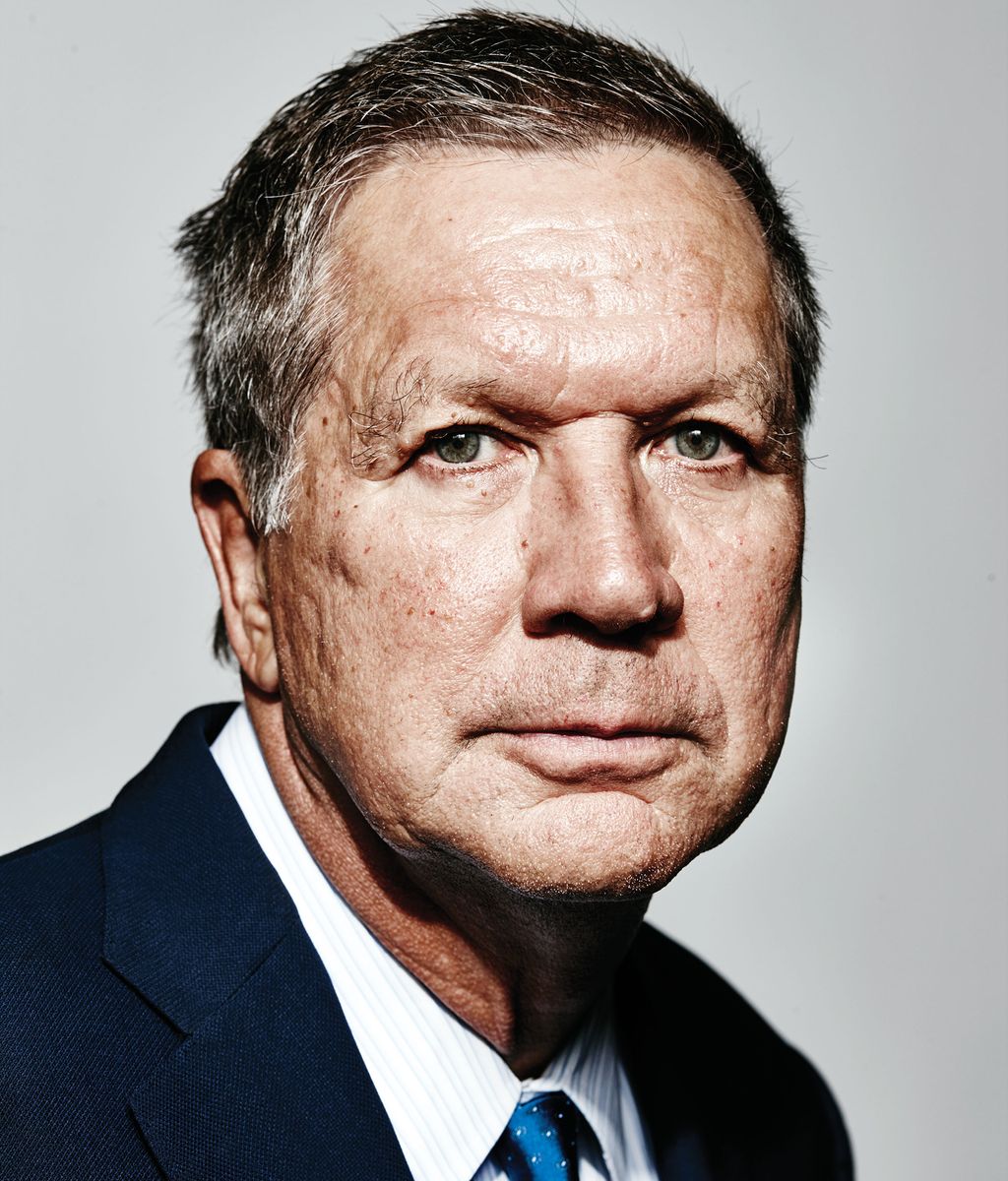

One year after his failed run at president, John Kasich is plotting his path to another, his third, for 2020.

You’ll remember Kasich from the last campaign, as his party caved to Donald Trump. At the Republican debates, he was the one at the farthest end of the stage — television Siberia — flapping his arms and shaking his head while making a case for himself as the voice of reason. “The debates were ridiculous,” he told me recently over dinner at an Italian restaurant in Alexandria, Virginia. “It was a one-line, let-me-see-if-I-can-get-on-the-news-tomorrow.”

It had been a long day, and Kasich was hoovering his spaghetti and clam sauce like a man who eats for fuel. “I wasn’t pitching myself. I was being myself.” Earlier, Kasich had staked out his place in the Republican landscape: “I think we need to be pro-environment. I think we need to be pro-immigrant — of course we need to protect our borders. I think we need to completely redo education. Every piece of education now is behind the times and a hundred years old. Look, I loved Ronald Reagan. I met Ronald Reagan. But Reagan was then. Now we gotta move on.” He came to his point: “I have a right to define what it means to be a conservative and what it means to be a Republican. I think my definition is a lot better than what the other people are doing.”

In Kasich’s view, the election of Trump and the complicity of party leaders represent a widespread abandonment of good American values — “a momentary lapse of reason,” he says, “to quote Pink Floyd.” A believing Christian, Kasich talks about his contrasting vision as a “revival”; he has a yearning to restore to American citizens the “basic principles of caring, of love, of compassion, of connectedness, of a legacy … There has to be a fundamental change, in my opinion, with all of us. I’m willing to be part of that. I want my voice to be out there. I want it very, very much.”

Kasich is perhaps an unusual standard-bearer for the Trump resistance, with a complicated relationship to the Republican Establishment in whose name he is now, functionally, crusading. He rose to prominence in Congress as a swaggering combatant during Newt Gingrich’s revolution and, even having served as governor of Ohio since 2011 — an established Republican if ever there was one — he still thinks of himself as an upstart outsider. “I was in the tea party before there was a tea party,” he boasted when he was running for governor. While his lack of deference has populist appeal, in theory, it is not so welcome among certain wealthy Republican donors. During the 2016 primaries, the unsurrendering Kasich outlasted every other contender but raised only $37 million. (Jeb Bush, who dropped out five months before the convention, raised four times that much.) “Why didn’t I have more money?” he repeated to me, still somewhat bitter. “Because people don’t want to create a leader, they don’t want to make a winner, they want to follow a winner. People say, ‘Do you want to run again?’ All that other stuff. Well, how much money are you going to give me?”

In person, Kasich is like a manic barkeep who talks too much but also makes some sense. Bill Paxon, a friend who served with him in Congress, describes his energy as “that of a 12-year-old boy with a frog in his pocket.” He can be hyperfocused and detail-oriented but also, by turns, impatient, cranky, and self-regarding. I met with Kasich over several days, in Columbus, Washington, D.C., and New York, in a whirlwind that, a year before the midterms, nonetheless felt very much like a campaign tour. In a greenroom at MSNBC, after critiquing the hairstyles of the male guests on set, he wondered aloud how I thought he looked. “Do I look youthful? What makes a person youthful?” he asked, before veering off into the semantic differences between “weak” and “meek.”

It’s an interesting time for a meditation on the varieties of political will. Kasich is not entirely alone in speaking out against his party’s leader: Over recent months, a succession of Republicans have felt provoked or compelled to call out the president — most recently Senator Jeff Flake, who called Trump “reckless, outrageous, and undignified” from the Senate floor and seemed, at least to many liberals, to be bravely speaking for a silent coalition. Two weeks earlier, Senator Bob Corker had called the White House “an adult-day-care center.” But neither Corker or Flake is running for reelection. John McCain, who has also spoken out, is ill with cancer. Among those Republicans angling to retake the party from its current leader, it is Kasich who is the furthest ahead. He set himself up as a public enemy of Trump two full years ago — running an early campaign ad that compared the mogul to Hitler and another, well after Trump had sewn up the nomination, that was aimed at convention delegates and that presented a fantasyland in which he, not Trump, was the nominee.

Kasich, whose final term as governor ends in 2018, is still hawking that vision. He knows he faces a strategic imperative: He must dramatically expand his name recognition in this fallow period before the next race begins. “What I didn’t fully appreciate,” he writes in Two Paths, his account of the 2016 election that reads very much like a campaign book, “was how little known I was outside my home state of Ohio … It’s not that I wasn’t well known, I was learning. I wasn’t known at all, and that would turn out to be a major strike against us.”

But Kasich 2020 is not just a media proposition. Kasich is a sitting governor exploring a run against a president of his own party — a starkly unusual circumstance. He retains a skeletal campaign staff, and they are helping him to think through his options: Should he run as a Republican in the primaries or as an Independent in the general election? A primary run is plausible, strategists say, if Trump’s approval ratings among Republicans fall below the high 70s, where they’ve been, and Democrats prevail during the midterms, signaling a loosening of the stranglehold of the far-right base on the party. A third-party run is optimal if the major-party candidates represent ideological extremes. Kasich has not declared he’s running, and everyone I spoke to preempted their hypotheticals with caveats. In the Trump era, two years is an eternity. “Look,” said Stuart Stevens, a strategist who advised Mitt Romney on his 2012 run. “We could be at war with Iraq. We could be at war with Iraq and North Korea. We could be at war with Canada. Who knows?” But among the party’s intelligentsia, all agree there is a common wish that the White House be occupied by a different Republican.

Any run by Kasich amounts to an open GOP rebellion, the declaration of a secessionist movement. Kasich threw down the gauntlet when, even under pressure from his party, he refused to endorse Trump. Gingrich, once Kasich’s mentor, now regards Kasich as an apostate. “His behavior is not that of a regular Republican,” Gingrich told me.

Kasich acknowledged being sanctimonious, even bullying sometimes. He is famous for his temper and has a reputation for late-night, wine-soaked “2 a.m. on the porch” debates, he says, which can necessitate contrite phone calls the following day. During the primary season, he made headlines for scolding a major GOP donor during a Koch-brothers conference when she questioned his decision to expand Medicaid in Ohio. “I don’t know about you, lady,” he said, “but when I get to the pearly gates, I’m going to have an answer for what I’ve done for the poor.” Twenty people left the room.

This time around, on the advice of his handlers and his wife, Karen, he is trying to contain his high-minded anger and spin a virtue of his self-righteousness. “You think I’m not nice?” he asked me at dinner. “Do I have a bad edge? A mean edge? A kind edge? Or an edge?” But he conceded the point: “People know that I will browbeat them into submission,” he said.

During a state cabinet meeting in Ohio, I heard him tell a story featuring his friend, actor Warren Beatty. “I said to him, ‘You’re so humble. You have so much humility!’ I go to his house. There are no statues, no — you know — no posters, big Hollywood things.” Then, as if to preempt an argument about his own grandiosity, he openly confessed to his flawed nature. “My biggest worry is that I will be hoisted on my own self-righteous petard.”

But when I passed along Gingrich’s comment, that he wished Kasich would be more like a “regular” Republican, Kasich’s equanimity vanished.

Even when controlled, Kasich holds his anger just beneath the surface: His jaw clenches and his long fingers twitch unconsciously and spastically, like minnows in a net. “Maybe he should be one,” is what he said.

A primary challenge to an incumbent president is generally seen, in the American two-party system, as a kamikaze mission. This happened in 1976, when Ronald Reagan challenged Gerald Ford and Jimmy Carter won. It happened again in 1980, when Ted Kennedy challenged Carter and Reagan won. An Independent bid is an even dicier proposition. Without the support of an established political infrastructure, a third-party candidate requires massive contributions to a cause whose prospects are very, very dim. Teddy Roosevelt tried it in 1912 and handed the election to Woodrow Wilson. The last time an Independent won a presidential race that included an incumbent was never.

These are not conventional times, and this is no longer the party of George W. Bush, who earlier this month implicitly rebuked Trump for his isolationism, nativism, and “casual cruelty.” But though they wring their hands over Trump at private dinners, few elected Republicans have done much while in office to stand up to the president.

In one sense, Kasich has never stopped running against him. He stayed in the primary race until the bitter end and quit only when he ran out of runway. He went back to Ohio, wrote a book, and got right back in there. All along, he has had a very savvy co-pilot. In 2015, he hired the Republican strategist John Weaver to lead his primary bid, and Weaver — most known for John McCain’s two presidential runs and the campaign bus he named Straight Talk Express — has remained on the payroll ever since. Kasich talks to Weaver many times a day from his flip phone. Weaver is known for his bleak temperament, and he nurses what can only be described as an unrestrained loathing of Trump. On Twitter, where he seems to live, he won’t use the word president in connection with Trump without deploying quotation marks. “ ‘President,’ have you no shame?” he wrote after Trump insulted the widow of a soldier slain in Niger. “Chump ‘president,’ ” he continued. “Even by his (no) standards, disgusting.”

But Weaver has counseled Kasich not to follow his example and to keep his criticism to the policy realm. “If he reacted like I do to everything that the president does, he wouldn’t get anything done,” he told me. “He has chosen not to get into a character dispute with the president like Bob Corker did. I like Bob Corker, but he’s voted with the president at every turn.” The better tactic, Weaver believes, is for Kasich to embody the empathic, optimistic alternative to Trump. “He’s going to be a happy warrior about how to move forward,” Weaver said. “He’s constantly counseling me to be on the sunny side of the street.”

In Kasich, Weaver sees parallels to McCain — and opportunities to become what McCain never would be. He comes across as real and unpackaged; he has experience governing and cares about policy. “Even more than McCain,” Weaver adds, Kasich is focused on the lives of his constituents. In 2016, Kasich held a series of town halls, and at one, in February, a college student from Georgia stood up and told Kasich his story. A close friend had committed suicide, and his parents had divorced, and then his father got laid off. Wearing a giant Kasich sticker on his hunting vest, he asked the candidate for a hug. Both wept. Kasich, whose own parents were killed by a drunk driver as they sat in their car in a Burger King parking lot, mounted the stage like an Evangelical preacher. He said, “There are not enough people who are helping those who have no one to celebrate their victories, and we don’t have enough people that sit down and cry with that young man. Don’t you see, that’s what it’s about?”

The town halls “were so intimate that you felt you were at a scene you shouldn’t be at,” Weaver says. He believes authenticity goes a long way with voters and that they will be forgiving of a candidate who is transparent about his failings and learns from his mistakes. Which may be why Kasich’s stump speeches now include refrains like “I’m flawed,” “I’m fallen,” and “I’m a hypocrite.”

But voters want to hear about policy, too, and, at the moment, Kasich says he is staying in the middle lane. “I got to make the tea party happy?” he asked rhetorically during one of our conversations. “I got to make the left wing happy? I don’t look at it that way. I got a message that I think I can sell to anybody.” His positions on health care are a case in point.

Kasich talks a lot about expanding Medicaid in Ohio, a move that automatically disqualified him from the White House in the minds of the right’s hard-liners, for it implied an endorsement of Obamacare — the mechanism through which he was able to obtain that money and the disavowal of which had become the litmus test for true allegiance to the GOP. (Fellow conservatives in Ohio dubbed him a RINO — Republican in name only — and earlier this year Mike Pence attacked him for it, too.) But as governor, necessity prevailed over ideology. With a runaway drug problem in Ohio and rising ER visits and a growing elderly population, Kasich knew he could find a million uses for the money. “When you become a governor, you take on a whole different role than if you’re someone just living on Mars. It was not even a thing I had to think about,” he said. In Ohio, nearly 700,000 people have received Medicaid expansion money, mostly for drug treatment and mental health.

And in late August, as the Republican effort to repeal the Affordable Care Act reared its head for the second time, Kasich, together with John Hickenlooper, the Democratic governor of Colorado, released their plan to stabilize the health-insurance markets and preserve, at least temporarily, the ACA. In stark contrast to the blunt and hurried proposals by federal lawmakers, the Kasich-Hickenlooper plan was notable for its weediness. In a concession to the left, the plan expressed support for the individual mandate (a heresy in the Republican Congress). In a concession to the right, it insisted on making the waiver process more efficient and accessible. (The Alexander-Murray Obamacare fix circulating in Congress uses a similar approach.) When reports circulated that Kasich and Hickenlooper were planning a joint run for the White House, Kasich beat them back, protesting with a twinkle that no one can pronounce his name (rhymes with “basic”) and Hickenlooper’s won’t fit on a bumper sticker.

Practically speaking, “moderate” is a winning stance only if Kasich runs as an Independent against candidates who represent the furthest, most motivated flanks of their parties: Trump on the right and someone like Bernie Sanders or Elizabeth Warren on the left. Then the whole vast center is up for grabs. And even in that case, “the first thing you’re going to have to do is have a very significant legal budget to get on the ballot and then figure out how to get $100 to $150 million to run a general-election campaign,” says Tom Rath, who served in Kasich’s New Hampshire operation last time around. A centrist approach doesn’t work if Kasich needs to win over the Republican-primary voters who continue to be Trump’s hard-core fans. And it doesn’t work if the Democrats put up another centrist like Joe Biden, who has Kasich’s blue-collar authenticity — but with more charisma, more star power, whiter teeth, and a lot more name recognition.

When I mentioned Biden, Kasich lit up — an insight into how he sees his position in the political marketplace and the challenge he faces building a coalition powerful enough to oppose the base within his own party.

Biden, he told me, “is very effective. He’s an old lunch-bucket Democrat. He’s a day at the mill and a shot and a beer and we’re going to give everybody a chance. You may be struggling, and it costs too much for your kids to go to college, but your kids are going to be something. I don’t know if the party wants it, because they’re so far left now, dominated by a handful of elites that drive them harder and harder left. If you’re a Democrat and you want to win, you have to figure out how to go around those gatekeepers.”

One of the things Kasich likes best about governing is the chance it gives him to play Lone Ranger. I saw him bestow Ohio State football tickets on the family of two girls who were being bullied in school — and then also ask his staff to explore the possibility of moving the girls to a private Christian school run by a friend. In the elevator of a Washington, D.C., hotel, he offered a couple of middle-aged tourists, strangers, a tour of the floor of Congress. His staff regards him fondly and with exasperation: He refuses to hire a speechwriter. I saw him, several times, berate the people who work for him, including in the cabinet meeting, where he called out his higher-education secretary. “That stuff is dysfunctional!” he said.

Kasich was born in a steel town near Pittsburgh. His father was a postal worker and a Democrat. He became a Republican because “I don’t like being told what the rules are,” he told me. “I kind of looked at the Democrats as very top-down, and I looked at the Republicans as more free-flow.” The story goes that when he was a freshman at Ohio State, someone in his dorm broke a window and all the guys on the floor had to chip in to pay for it. Kasich, who didn’t have disposable income, objected strenuously and went straight to the university’s president to complain. The president, named Novice Fawcett, heard him out; then he mentioned that he was about to fly to D.C. to meet Richard Nixon and, capitulating to Kasich’s entreaties, carried a letter from the student along. The letter earned him, at 18, a visit to Nixon in the Oval Office and an object lesson in the benefits of insistence.

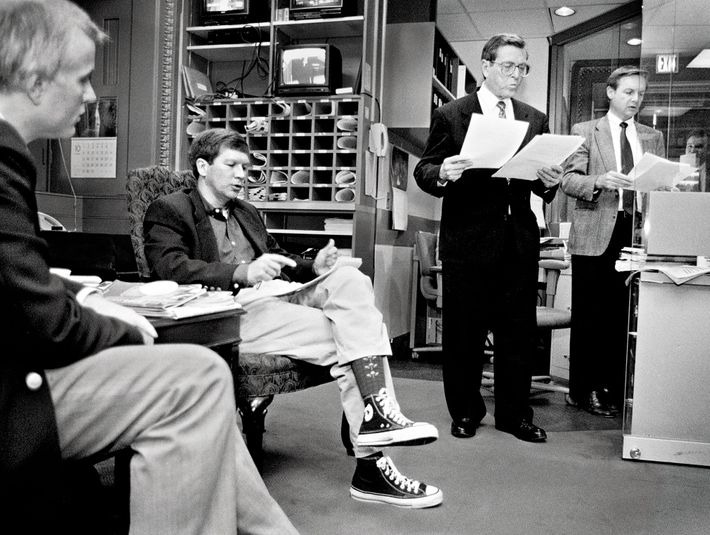

He ran for state legislature when he was 26. By 30, he was elected to Congress. In the early days, “we were nobodies,” remembers Dave Hobson, a fellow Republican representative from Ohio. “We were wandering in the wilderness.”

“He didn’t have a car in Washington,” said Hobson, and was always having to mooch a ride. “John was cheap. He always was cheap.” As a junior congressman, Kasich had a position on the House Budget Committee and became obsessed with balancing the budget, talking about almost nothing else, and in 1989 he presented his first budget to Congress. It received only 30 votes. “It was his friends and people who felt sorry for him.”

But Kasich rose with the Republican tide that elevated Gingrich in 1994. At 42, he became chairman of the Budget Committee and a member of the Republican leadership — at a time when Gingrich was leading a wholesale remodeling of the party and the way it viewed the opposition. Today, Kasich sermonizes on the fundamental importance of political civility and the bipartisan process, but back then he was a star player for the increasingly bellicose and intransigent empowered right.

Gingrich’s Contract With America promised massive tax cuts and a balanced budget by 2002. And in September 1995, Kasich, a good soldier, spearheaded the drafting of the representatives’ budget. It contained cuts to student-loan programs, agricultural programs, space exploration, and subsidies for the working poor.

In June 1995, President Clinton vetoed that budget. The standoff continued through the fall, and in September, Kasich’s committee proposed more drastic cuts, including a$270 billion reduction in Medicare spending. (It would not, he assured, jeopardize the quality or accessibility of health care at all.) In the winter, Congress gave Clinton an ultimatum: Pass the budget or we’ll shut down the government. In a precursor to the present dysfunction, the two parties held their positions and refused to budge. “It’s almost five to 12, and we’re in the movie High Noon, and we’re sitting in the saloon,” Kasich said theatrically at a press conference in November of that year. Clinton vetoed it again, and the government shut down, for 27 days.

Behind closed doors, Kasich was more of a problem-solver and wonky negotiator. He was on the bipartisan team that for almost a year hammered out a budget both sides could live with, which Clinton signed in April 1996.

Alice Rivlin, the White House budget director at the time, has a photo hanging in her office of the principals in that negotiation: Clinton, Gingrich, Pete Domenici, Trent Lott, Bob Dole, and Leon Panetta, among others. Kasich is grinning like a Boy Scout. “John looks so young,” she says.

Panetta, then Clinton’s chief of staff, recalls Kasich as “ambitious” and “a good apostle,” someone “who did not want to go out of his way to offend those in power in his party.” But he did help steer his party toward a compromise agreement. Back then, there was a psychodrama to politics that everyone understood as a performance — “a playacting,” Panetta says, “that has to go on that conveys the impression that you’re fighting the last battle.” Both sides knew that they had no choice but to sit down together. Today, no one seems to understand that public bluster is only one-half of a policy fight, and Panetta speaks of Kasich with the fondness of an old war buddy. “I could always pull him aside and say, ‘Cut the b.s., John. You know what it means to do the right thing.’ ”

My longest day with Kasich started in Columbus. Kasich had arrived home very early that morning from a field trip with staff to see his team, the Pittsburgh Pirates, play. After lunch, he signed a bill raising sentencing guidelines in certain cases of domestic abuse. Then the historian David McCullough, a fellow Pittsburghian, dropped in to give a brief talk to the cabinet, and the two shared a moment of mutual admiration and reminisced about the Duquesne Club, the elite gentleman’s club where McCullough’s father was a member and Kasich’s was not. “When I was a kid, I would walk past,” Kasich said, describing just how far from Establishment power he felt as a child. “There was a red carpet, and there was a general out in front. My buddy and I would look inside, and he would step in front of us, and we’d salute him. About 20 years ago, I found out who the general was. He was the doorman. Okay?”

The McCullough meeting backed up into the cabinet meeting, where Kasich introduced and flattered an Amazon executive who was presenting a PowerPoint on customer service, then he hurried to an outdoor ceremony commemorating 9/11 in which a dozen Girl Scouts, nearly blue with cold, planted 3,000 flags on the statehouse lawn. In the meantime, all the statehouse speakers in the country had assembled for cocktails, and before assuming the podium to make his remarks, a standard speech about “governing from the middle,” Kasich got into a tussle with Robin Vos, the Republican speaker from Wisconsin, who amicably approached the governor and then swore at him for adding his name to a Supreme Court brief opposing Republican gerrymandering in Wisconsin. They had a heated exchange in which Vos accused Kasich of betraying his party. (Vos did not respond to requests for comment.)

The governor was due to fly to Washington later that night so he could flog his joint-health-care plan the next day — the same day that Republican senators, this time Lindsey Graham and Bill Cassidy, were trying once more to eviscerate the ACA. Here was Kasich at his most political, talking to Weaver on the phone; fielding a call from Rick Santorum, who was urging him to support the Republican plan; playing phone tag with Chris Christie; and counting votes from the front seat of the car. Kasich’s health-care guy assured his boss that Graham-Cassidy was dead, or at least on life support, and then all of a sudden it wasn’t again. And in the midst of all this, Kasich had a fight with his wife. One of his twin daughters had a school project due the next day — an interview with him, in fact — and he hadn’t had time to answer the questions. You have to make time, his wife had said. This seemed to rattle him most of all.

On the flight east, I was pressing him to reflect on Trump — in particular, on the Republican Party’s own historic role (and, by implication, his personal responsibility) in enabling Trump’s rise. Kasich wouldn’t budge. “He’s just a manifestation,” Kasich said, “of what’s been happening for a long time. That’s what I think. This has been a long journey down this road. Judge Bork. John Tower. Bill Clinton. Newt Gingrich. Tom Foley.

Jim Wright. I mean, come on. These were things that brought out the worst in people. Brought up controversy and a dividing of the political system.”

It’s easy to see the tactical necessity of keeping to the high road — though, then again, maybe not. If these really are unprecedented times, and Trump an unprecedented disaster, then why does the Republican Party continue to insist on caution? If Kasich really is a man of conscience, then why doesn’t he say what he thinks? “We’re missing a sense of outrage about how far we’ve diminished the dignity of the presidency. And how far we’ve gone in the failure to acknowledge the responsibility that elected officials have to govern,” said Panetta. “I think Kasich has probably come as close as any Republican, but at some point it’s the Republican willing to really acknowledge how bad things have gotten and how much of a tragedy Donald Trump is to our way of governing who’s going to be able to break through politically.” Kasich, when pushed on this, demurred. “I’m not going to stand on the stage and set myself on fire,” he told me. He added, “I have no reason at all to suspect corruption or criminal activity.”

Over dinner, Kasich acknowledged that he did try to take on Trump during the primaries. He defended the Iran nuclear deal. He said you couldn’t kick all the Muslims out of the country. Trump voters booed him, he said. There was no space for even reasonable disagreement. “I didn’t say anything that was, like, ‘Rip their heads off,’ because when you’re a governor, you can’t say crazy stuff because you actually have to be a governor.”

Then Kasich’s Ohio communications guy, a slim, affable man named Jim Lynch, interjected with some governing business, mentioning that he’d spoken to the organizers of the Ohio State Fair. Apparently the governor had expressed his displeasure at the bands playing there. He was interested in headliners who would reliably turn a profit. “Everybody will come to see the Beach Boys. Everybody. Young, old, rich, poor, everybody.”

Lynch wanted to raise the question of whose job it would be, going forward, to pick the bands, and Kasich cut him off. He didn’t want Lynch or some liaison picking bands. “We’ll go get the bands,” he said. “Let’s get Queen.”

I interrupted. But Freddie Mercury is dead.

“What’s his name, Adam Lambert, is playing Freddie Mercury,” Kasich said. (Lambert, an American Idol contestant, has become the front man for a new iteration of the glam-rock band.) “He’s doing great.”

As a younger man, Kasich had a reputation for loving rock and roll, and, at 39, even once tried to linger on the stage at a Grateful Dead concert. (He was removed by security.) I asked him what music he’s listening to.

“Why do you want to get me into that stuff now?” he asked. “I like music. I’m just not going to go down that path and be Mr. Cool. My music’s appropriate, okay? People think that because of the music I listen to — it must be from my daughters. They’re wrong.”

I’m interested in your daughters’ music, I said.

“My wife and my daughter just went to see Lady Gaga. I do like Lady Gaga, I think she’s fantastic. But I’m a bit more into … I mean, I like Bieber. Okay?”

In speeches, Kasich likes to talk about what he’s done for Ohio. He cut the budget deficit by $8 billion (a figure disputed by some) and raised the surplus to $2 billion. He says he’s created 400,000 jobs. Still, under Kasich, Ohioans — like so many in the industrial Midwest — are suffering. Ohio has one of the highest drug-related-death rates in the country; overdose deaths rose by a third to 4,000 last year. Job growth is lagging behind the national average, and wages are, too. College is costly, immigration and diversity are low, and infant mortality is 24 percent higher than the national rate. Certain of his innovations, taken from the conservative playbook, have had dubious effects. Kasich is a strong proponent of charter schools (and for-profit prisons), but he presides over a public-education system that dropped in Education Week’s national rankings from fifth place in 2010 to 22nd in 2016. In 2011, Kasich endorsed the gutting of government unions (though it later failed a ballot referendum), and last year he signed a bill into law that bans all abortions after 20 weeks — and then boasted that he didn’t sign the law that banned abortion after an audible fetal heartbeat.

His is, in fact, a rather conventional conservative résumé. That he’s able to market himself as a moderate signals just how immoderate the right has become. And that he’s able to market himself as a bomb-throwing outsider signals just how fully the party has thus far lined up behind its bomb-thrower-in-chief.

But on the flight from Columbus to Washington, D.C., Kasich didn’t really want to talk about policy. (“Everybody ought to just take a chill pill,” he said later about abortion, adding that his wife is pro-choice and “we don’t sit around arguing about this.”) He didn’t want to talk about politics. He didn’t want to talk about who was responsible for the rise of Trump, or what Trump means for American history, or the risk Trump presents to our constitutional protections. “That’s all small ball,” he said to me.

“The Trump thing is not what bothers me,” Kasich added. “What bothers me is when people across our society begin to say, ‘Values don’t matter.’ Or, ‘I don’t believe in God.’ That’s what bothers me. It’s depth.”

Kasich joined St. Augustine, a six-year-old Anglican church in Westerville, Ohio, because he’s friendly with the pastor. (The Anglican Church in North America broke away from the Episcopal denomination over the question of same-sex marriage; in 1996, Kasich voted against gay marriage and for the Defense of Marriage Act.) “It’s not like I go to church and fall into some frozen state somewhere, or I raise my hands or roll around in the aisles.

I go to church for two reasons. One is to say thank-you for my blessings. And two is because, as one minister told me, ‘You showing up in church is good for the other people because you’re a big shot, you know.’ ” Kasich likes to read Christian authors, and if he likes what they have to say, he calls them up. “I just called up the guy who runs Duke Divinity School and had a one-hour conversation. That’s how I do things.”

What Kasich really wants to talk about is his belief that for the nation to heal itself, individual Americans must reclaim a higher sense of interconnectedness and personal responsibility, which has been lost in the pursuit of profits and celebrity. He is moved by the example of the Kardashians, who put up $500,000 to help the people of Houston after Hurricane Harvey. And he is moved that a golfer named Stacy Lewis, who hadn’t won a tournament in three years, promised to give all her winnings to Houston, too, and then after she won, one of her sponsors doubled the sum. “These little acts of good and kindness, they matter. They make the world turn a little differently. Lawmakers, we have our place. Should you just bring back the days of the robber barons? Of course not. But we’re not going to fix all the things that ail us by writing a law. If Donald Trump all of a sudden were not president, do you think everything would be great? Do you think all our problems would be fixed? I don’t think so.”

He’s like a steamroller when he gets going, and he shrugged me off when I suggested that enacting laws might be useful to protect people whose civil rights are endangered under Trump. “You want to wave a wand and make it go away. It’s like, if you get to be fat, you didn’t get to be fat overnight, and you won’t get skinny overnight. You got fat over a period of time of doing things that are unhealthy. It doesn’t get fixed overnight. That’s what’s so frustrating to people who yearn for a better situation, and that’s why when I say there’s no magic to it, this really bothers some people.

“What does the Jewish tradition say? It says, ‘Repair the world.’ I like that word repair, it’s sort of a small word. Repair. I’m going to repair my car. I’m going to repair my socks. I’m going to repair my house. You’re not capable of anything beyond repair. None of us are,” he said. Raising a good kid, doing a good job, being a good person — that should be enough. Kasich turned to his communications guy, Lynch. He wanted to know, did Lynch show me the Holocaust memorial?

In 2014, after a long fight, Kasich unveiled one of two Holocaust memorials erected on statehouse property. He was moved to do so after hearing a 77-year-old woman from Canton describe her escape from Lithuania, hiding in a dresser drawer as a 6-year-old girl while soldiers’ dogs tried to sniff her out. Kasich’s own daughters, Reese and Emma, were 11 at the time. It was at a local Holocaust remembrance event, and when Kasich took his turn at the podium, he said that the state of Ohio hadn’t done enough to remember “man’s inhumanity to man.” On the spot, he proposed an homage to rectify that oversight. Over the objections of his own Republican legislature, Kasich persisted until he wore everyone down. The memorial was designed by Daniel Libeskind, and Kasich is especially moved by the inscription, which quotes from the Talmud. “If you save one life, it is as if you have saved the world.” He wanted to know why I hadn’t seen it.

“We didn’t have any downtime,” said Lynch.

Kasich became hectoring. “Why couldn’t you say, ‘I want to take you for five minutes and show you this’? Why wouldn’t you take her out there so she could see the thing that says, ‘If you save one life, you’ve saved the world?’ You did not do that.”

It went on like that. Lynch tried again to protest, stammered, and then finally relented. “I should have taken her, sir. Yes.”

Then, as the plane began its descent, Kasich presented us with an ethical dilemma. If one good woman saves a single Jew during the Holocaust, and Oskar Schindler saves a thousand, who is the better person? Lynch was silent. The chief of staff said Schindler. Kasich looked at me. “They’re the same,” I said. “Thank you!” he shouted, slamming his palm on the armrest of his airplane seat. “It’s quality, not quantity. The bigger platform you have, the more good you can do, but it doesn’t make you better than the guy down the street.” He chuckled, elated at having imparted this lesson. “That’s what I’m trying to say.”

*This article appears in the October 30, 2017, issue of New York Magazine.