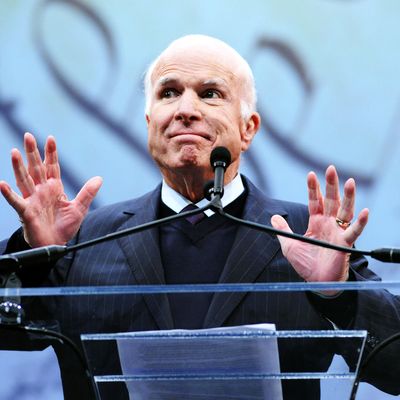

Last night, accepting an award from the National Constitution Center, John McCain denounced the Trump administration’s ideology in terms that sounded harsh, and that upon reflection were even harsher. Without naming Trump, but without needing to, the Arizona senator dismissed “some half-baked, spurious nationalism cooked up by people who would rather find scapegoats than solve problems,” likening it to “any other tired dogma of the past that Americans consigned to the ash heap of history.” Here McCain was comparing the worldview of a president of his own party to communism and fascism — a rebuke even deeper, in a way, than Senator Corker comparing him to a doddering half-wit. Corker attacked Trump’s competence. McCain attacked his intentions.

When he thumbs-downed the Republican health-care plan three months ago, McCain shocked the news media and members of both parties. He had previously displayed barely any interest in the issue at hand, and for more than a decade served as a largely reliable partisan vote that belied his reputation as a “maverick.” Indeed, the maverick legend had grown so stale that many people, especially liberals, dismissed it as nothing but a legend. But McCain is making it perfectly clear that, in the final chapter of his political career, he has gone into opposition again.

If you formed your first impression of McCain during his presidential campaign, you probably see him as an orthodox Republican who deemed Sarah Palin fit for the presidency and voted with his party nearly every time. But the McCain story goes further back. McCain began his career as an orthodox Republican. Having been embarrassed by a campaign-finance scandal, McCain embraced the singular heresy of crusading for campaign finance reform. When he ran for president in 2000, McCain gained traction with the electorate by opposing George W. Bush’s plan to give tax cuts to the rich, bringing the wrath of the party Establishment down on his head.

The aftermath of that episode left McCain completely, if temporarily, unmoored from party doctrine. Not only did he vote against both the 2001 and 2003 Bush tax cuts, but McCain joined the Democrats on every major domestic dispute of the Bush era: a patients bill of rights, auto-emission standards, reimportation of prescription drugs, closing the gun-show loophole, forcing disclosure of executive compensation, federalizing airport security, and requiring the regulation of greenhouse-gas emissions. McCain was identifying himself as a “Theodore Roosevelt Republican” — a pointed contrast to the staunchly pro-business cast of the Bush-era party — and came within a hair of leaving the GOP altogether and caucusing with Democrats as an independent.

But McCain never reconsidered or modulated his ultrahawkish foreign-policy views. The political salience of the Iraq War (where his views lined up with the GOP) and his ambitions to become president brought him back into the party fold, and beginning in 2004, McCain’s constant stream of deviations from the party line ceased. After he managed to make himself sufficiently acceptable to his party Establishment to capture the nomination, he seemed to carry his bitterness with the young senator who defeated him through the eight years of the Obama presidency.

The simple heroic story about McCain often told by adoring reporters is a dramatic oversimplification. But so is the simple story told by liberal critics of a bloodthirsty reactionary whose maverick pose is a pure fraud. McCain is a complicated figure buffeted by a mix of ambition, principle, vanity, and strong beliefs in a handful of areas. Like many people, he is capable of acting in both admirable and venal ways, depending on the context.

Now McCain finds himself in a context that has brought out his heterodox side. The rise of Donald Trump has split the Republican Party elite. Certain traits predict the kinds of Republicans most likely to go along with the program: immigration restrictionists, isolationists, supply-siders who only care about whether the president will sign their tax cuts, politicians with ambitions to run for president in the future, support for conservative orthodoxy in general. The kinds of Republicans most likely to find Trump repulsive include neoconservatives, immigration doves, women, and institutionalists. Aside from being male, McCain has all the traits that would predict anti-Trumpism.

Whereas McCain’s bitterness with the 2008 election encouraged his opposition to Obama, now his bitterness with the man who mocked him for being captured in Vietnam pushes the other way. Gabriel Sherman’s reporting for New York last February suggested that McCain saw himself eventually playing a decisive role as an anti-Trump Republican, but that he needed to bide his time. “I can’t be the car alarm that always goes off. If I am, I’m not effective,” he told John Weaver. Sherman quoted a former adviser laying out the path:

“McCain is a savvy political operator,” a former adviser said. “He sees a critical mass building demanding investigations. He weighs in at the decisive moment to turn it to calls for a select committee, and ultimately he’ll be the person that tips it to calls for an independent-counsel investigation.”

And then McCain was diagnosed with cancer, and the luxury of patience was no longer available to him. The schedule has suddenly accelerated, and the version of McCain now on display is the one he clearly wants to be remembered as.

Perhaps even more telling than his speech denouncing Trumpism was a McCain tweet endorsing a William Kristol column in The Weekly Standard that all but calls for the breakup of the Republican Party. (“It would be foolish to dismiss the case for independent candidacies or new parties. We are, after all, citizens first, not partisans.”) It would be unrealistic to expect McCain to leave his party. But there is almost no doubt now that his final act will be as a leader of the Republican rebellion.