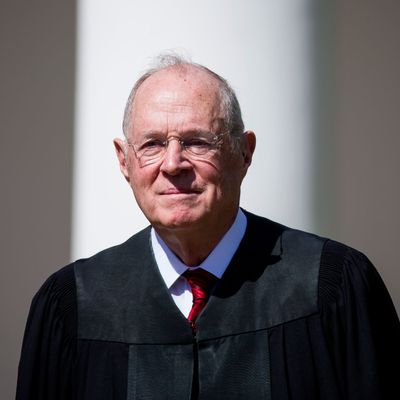

The U.S. Supreme Court today heard oral arguments in the much-discussed and potentially monumental case of Gill v. Whitford, a challenge to Wisconsin’s 2011 state legislative redistricting map on grounds that it represents an unconstitutional partisan gerrymander. The very idea that there could be a process or result in redistricting that is too partisan —absent other factors like impact on minority voting — to pass constitutional muster (under the First Amendment and the Equal Protection clause) is relatively novel. But even as the federal courts drift in the direction of trying to curb partisan gerrymanders, the problem of identifying a measurement of “what’s too much,” which in turn determines the remedy, continues to represent a problem. And that will be the key issue in this case, since the certain swing vote, that of Anthony Kennedy, will be determined by that justice’s past pleas (most notably in the 2004 decision in Vieth v. Jubelirer) for a “workable standard” for policing partisan gerrymandering.

The 2–1 district court decision favoring the challengers to Wisconsin in this case heavily revolved around a new standard devised by two political scientists, called an “efficiency gap,” which essentially compares the voting performance of districts to what it might have been without such standard gerrymandering practices as “cracking” (spreading the minority party’s voters across districts so as to diffuse their power) and “packing” (concentrating the minority party’s voters in a minimal number of districts to “waste” their votes).

The majority of district court judges in the current case agreed with the plaintiff’s argument that an “efficiency gap” of more than 7 percent would be enough to guarantee the majority party continued control of a legislative chamber regardless of adverse trends, triggering judicial scrutiny. In 2012, actually, the Wisconsin efficiency gap was 13 percent for State Assembly races; Republicans won 60 of 99 seats despite losing the statewide vote.

An analysis by the Upshot of states (limited to those with at least five House districts) with congressional maps that would violate the 7 percent “efficiency gap” standard showed 13 states with impermissibly partisan gerrymanders, 12 of them favoring Republicans. You can see how the impact of judicial intervention in such states could be a really, really big deal politically, particularly if it is applied not just to future maps drawn in 2022, but retrospectively to maps that will be used in 2018 and 2020.

As expected, most of the justices seemed to split down partisan lines in oral arguments in the Gill v. Whitford case, as Sam Levine reported:

[T]hree of the court’s more conservative justices, John Roberts, Samuel Alito and Neil Gorsuch, seemed skeptical there could be a workable standard for courts to determine whether a partisan gerrymander violated the Constitution. The court’s more liberal justices, Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Elena Kagan, Sonia Sotomayor and Stephen Breyer, seemed more optimistic a manageable standard existed.

Clarence Thomas, as is usually the case, was silent during arguments, but there’s little doubt based on earlier cases that he’s with the conservative bloc on this issue.

Levine thinks Kennedy did not “tip his hand” during the arguments. But Ian Millhiser thought otherwise:

Justice Anthony Kennedy, the Court’s “swing” vote in this case, asked a number of critical questions of the lawyers defending the gerrymandered maps and literally no questions of [plaintiff’s attorney Paul] Smith. At one point, he appeared to grow angry with an attorney defending the maps for not answering one of his questions.

Millhiser also noted a striking aspect of the Chief Justice’s attitude toward this case and the entire issue of judicial scrutiny of gerrymandering:

The conservative flank of the Court’s defense of the map can be summarized in four words: “John Roberts hates math …”

Roberts … recoiled at the very idea that courts would play around with something so vulgar as maps and social science. In an especially candid moment, he told Smith that his primary concern is that, should Smith prevail, multiple partisan gerrymandering cases will be brought to the Court in the future, and the justices will have to explain why they side with a particular party in each case. If the Court’s response is a mathematical equation, Roberts feared, voters will find that answer unsatisfying, and the Court’s reputation will suffer.

What makes Robert’s position especially reactionary aside from its practical partisan impact is that “maps and social science,” and for that matter “math,” have increasingly dominated redistricting decisions by state legislatures, or at least those controlled by one party. They use sophisticated software to give their own party every conceivable advantage, in complete disregard of basic principles of representative democracy, as Joseph P. Williams recently observed:

[A]s big data gets better at identifying voters, and their preferences, with near-surgical precision, gerrymandering — partisan mapmakers’ ability to “pack” Democratic voters into single majority state districts and “crack” apart party support by diluting it through squiggly, irregular districts — is only going to get worse.

Legislative minorities can do nothing to help themselves in cases of partisan gerrymandering. That’s why the courts need to curb the practice, and why it’s important that Anthony Kennedy recognizes this as one of the last chances he may have for a landmark opinion.