Americans harbor certain deep-rooted impressions of the two parties, which have held for generations. Democrats are compassionate and generous, but spendthrift, dovish, and (in the views of many white people) indulgent of crime and prone to subsidize poor people who don’t want to work. Republicans are strong on defense and crime, but too friendly to business and the rich. What is striking about the Republican government is how little effort it has made to push against, or even steer around, the unflattering elements of its brand. President Trump and his legislative partners have leaned into every ingrained prejudice the voters hold against them. They have acted as if none of their liabilities even exist.

That is not the approach Democrats have taken in office. Bill Clinton famously fashioned himself as a “New Democrat,” angering his base on crime and welfare and declaring the era of big government over. Barack Obama did not position himself quite so overtly against his party’s brand — which had recovered in part because of Clinton’s success — but he did take care to avoid confirming political stereotypes. Obama frequently invoked the importance of parenting and personal responsibility. He did not slash the defense budget, and took pains to woo Republican support for criminal-justice reform. Obama tried repeatedly to get Republicans to compromise on a deal to reduce the budget deficit. Whatever the merits of these policies, they reflect a grasp of the party’s innate liabilities.

George W. Bush took some protective steps when he ran for president in 2000. Bush branded himself as a “compassionate conservative,” even the ideological heir to Clinton, but without the sex scandal, and distanced himself from elements of the party like Robert Bork and Tom DeLay. The rally-around-the-flag effect of the 9/11 attacks enabled Bush to use the Republican strong-on-defense brand, freeing him from the need to take any defensive measures. Bush ran for reelection as a standard-issue Republican. And after, as his presidency collapsed, his successors did little to distance themselves from its core agenda. In 2008, John McCain relied on the personal reputation he had built as a war hero and then during his few years as a maverick Bush critic. In 2012, Mitt Romney relied on the overhang from the great recession. Neither took serious steps to play against type.

In many respects, Trump did. He promised to raise taxes on himself and other wealthy people, give everybody terrific health care, break up the big banks, take on Big Pharma, spend a trillion dollars on infrastructure, and rewrite every trade agreement. These promises played a crucial role in helping attract downscale Democrats in the Midwest who had voted for Obama but now saw Trump as the economic populist candidate. In office, he has abandoned every one of these promises.

The unpopularity of Trump and his party is no mystery. Despite the continuing growth of the economy, public antipathy has swollen well beyond the normal backlash experienced by a party in control of government. The public simply hates everything they’re doing.

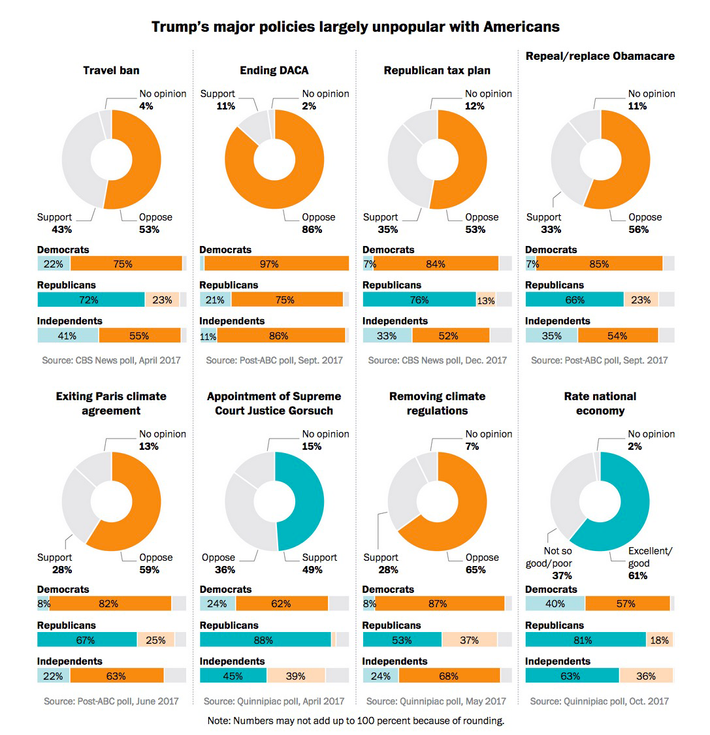

The Washington Post rounded up polling on Trump’s major initiatives. Other than the appointment of Neil Gorsuch, and the economic recovery Trump inherited, opposition to every other element is overwhelming.

What steps is Trump taking to correct this? Apparently none. On Thursday, he posed symbolically cutting red tape and excessive government regulations. (The pages were, in fact, blank.) Friday, he gave a speech to FBI trainees in which he touted his pro-cop credentials and mocked legal immigrants. He simply continues to reinforce the brand identity that has made him historically unpopular.

The way partisan stereotypes work is that people tend to believe them unless presented with very compelling evidence to the contrary. Republicans convinced themselves that they could pass a gigantic corporate tax cut, and that the public, which strongly opposes corporate tax cuts, would somehow reward them. Last month, Tara Golshan asked several Republican members of Congress about polls showing heavy opposition to corporate tax cuts. Most of them refused to believe it. “I would love to see those polls, because those aren’t polls of my constituents,” said one. “It would be interesting to see an accurate poll of 100 million Americans,” said another. “I don’t believe that poll,” said a third.

It is hardly the case that Republicans are united or even generally satisfied with their work over the last year. Far from it — in some ways, they are at each others’ throats. But almost none of the recriminations they express touch upon public opposition to their core agenda. Instead, Republicans in Congress complain about Trump’s tweeting too much, and Trump complains about Congress’s occasional displays of independence. Everybody blames somebody else for the failure of health-care repeal, without coming to grips with the inherent difficulty of taking insurance away from people when you promised to give them better insurance.

Amazingly, passing a deeply unpopular tax cut for rich people was a consensus solution to the party’s low standing with the public. Republicans have agreed on this step because some of them want it fervently (especially donors) and nobody opposes it. The notion of undertaking an ideological course correction and doing actually popular things seems not to have gained any consideration whatsoever.