Have Silicon Valley’s biggest companies become too powerful? This series examines monopoly and power in the tech industry — and what, if anything, can be done.

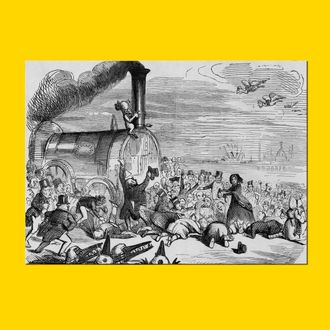

It’s very appealing, for the drama alone, to imagine some as-yet-unknown company driving Facebook into Myspace-like obscurity, or Alphabet being broken up, or whatever scenario for the demise of one of Silicon Valley’s five dominant companies you prefer to imagine. Not just appealing but natural to do so: We have in living memory at least a dozen examples of large and successful tech companies just failing, or becoming shadows of their former selves: Myspace is a ghost town owned by Time Inc. AltaVista and Friendster are long dead. Even Yahoo! and AOL, while still technically around, have become part of whatever Verizon-owned, centaurlike creation Oath can claim to be.

This recent history of “creative destruction” is important to Silicon Valley not just for its narrative neatness — Davids that become Goliaths, only to get toppled by new Davids — but for the protective shield it provides. Why be worried about Google’s power (or Facebook’s, or Amazon’s), when they’re each a bad decision against a more nimble competitor away from irrelevance? Surely Facebook can be Facebook’d, just as Myspace was? Surely Google will someday be disrupted?

The answer, unfortunately for people who enjoy the roller-coaster sensation of switching internet services every decade, is “probably not.” Frank Pasquale, a law professor at the University of Maryland who’s spent years writing about tech companies, remembers critiquing Google almost a decade ago to a tepid response. At the time, he says, economists and antitrust experts said he didn’t understand that, like Microsoft, Google would be knocked from its dominant position. Obviously, that hasn’t yet happened. “I’ve just been in sort of a state of frustration for a decade over this stuff,” Pasquale says. “Because I think it’s just so obvious that unless you have massive intervention at this point, you just have a massive, self-reinforcing accumulation of data, money, and power at these companies.”

“Self-reinforcing” is the key problem of the power dynamic inside Silicon Valley. Google’s size is inextricable from its success; the more people that search, the better its results are. A similar loop plays out on Facebook: The more friends that sign on, the better it is to use; the better it is to use, the more people sign on to it. This is the result of “network effects”: the well-known idea that for some services, quality relies in a large part on their ability to build broad networks. For social networks, search engines, ride-share services, and OS companies alike, a large network of users is fundamental to success — and a large network of users is about the one thing you can be sure that a new start-up won’t have. How can Google be disrupted if network effects mean its dominance will only lead to more dominance — and if you need a Google-size network to compete?

But network effects work both ways, as when users leaving Myspace in droves led even more users to leave, helping turn it into the relic it is now. While network effects may be instructive in understanding how the current crop of large-platform companies got where they are, they don’t entirely explain why those companies are so effective at holding their positions and making it hard for users to leave. Robyn Caplan, a researcher at Data & Society, suggests that it may be helpful to think of how they do this using another concept: path dependence, “which holds … that once a country or society has started down a particular road, the costs of reversal are very high.”

Network effects can help create path dependence, but they aren’t some sort of foolproof method for maintaining it. That requires the work that platforms like Facebook and Google have done getting other industries to buy into what Caplan describes as “the social and economic relationships that have been forged between publishers, platforms, intermediary ad companies, analytics companies,” and so on. For instance, media companies have spent so much time and money training employees on how to distribute articles and videos on Facebook, as well as how to use a specialized type of cookie called the Facebook pixel and other products developed by Facebook to garner whatever traffic they can, that they’re now extremely path dependent on the company and its products.

Or take Gmail, where you probably have an account. It’s a perfectly serviceable email option, and has the virtue of being free, but there are more secure services, like ProtonMail or Riseup, that’ll harvest less of your data. What would it take to get you to go through the effort of switching to another service at this point? Most of your social media is probably tied to your Gmail address, as well as accounts with your bank, shopping sites, a plethora of apps on your phone, not to mention all the other Google services you may use. The time and effort involved in extracting parts of your life from Gmail — even to switch to a clearly preferable competitor — would probably stop you from doing so.

Both network effects and path dependence derive from the same simple fact: The major players in contemporary Silicon Valley aren’t just software service providers, or purveyors of consumer technology, but “platforms” — that is, whole marketplaces unto themselves. As Pasquale puts it, “There’s no natural market force that’s going to replace these companies,” in part because “essentially they are not participants in markets, they make markets.” Because companies like Google, Facebook, and Apple both provide their own services — email, messaging, movie listings — and provide the means through which you access competing services, they have the power to decide what lives and dies online, and possibly even steal from others or favor their own products, something Yelp has long accused Google of doing. (And that the European Commission found Google to have done around shopping price-comparison sites.) As Ben Thompson has argued, this isn’t in and of itself a bad thing for the consumer from a product perspective — often, Google’s baked-in services are the best in class. But it is a bad thing for competition, and it certainly makes it more difficult to compete against it.

Of course, they’re not the first companies to recognize the potential of a platform business model — AOL and Microsoft both made a run at platform dominance in the 1990s. But Microsoft was, to use Pasquale’s phrase, “softened up” by antitrust actions taken against it by the U.S. government. AOL, for its part, entered a period of decline because technology broke the moat it had built around its users — once people switched to broadband from AOL’s dial-up connection, they weren’t spending most of their time inside the company’s walled garden of content anymore. This kind of sea change in technology is the likeliest path to the downfall of this era’s giants. But where widespread broadband internet was the kind of technological development that opened up the playing field for smaller and less well-funded start-ups, the exciting new technologies on the horizon — machine learning, self-driving cars, and augmented or virtual reality — all require enormous investments, not to mention the kind of vast troves of data only available to the biggest and most successful companies in Silicon Valley. Maybe more to the point, tech’s big five (Google, Facebook, Microsoft, Amazon, and Apple) are all heavily invested in those new technologies, an indication of smart management actively defending its position.

Which brings us back to the central problem: that whole self-reinforcing-power thing. Disruption isn’t impossible — a major technological change could do it, or losing enough users to make a service no longer useful — but every year that the biggest tech companies grow, they cement their dominance and make their demise less and less likely. The dream of motivated kids creating giant-killers in their dorm rooms and garages is a powerful one. Just not powerful enough.