In celebration of New York Magazine’s 50th anniversary, this weekly series, which will continue through October 2018, tells the stories behind key moments that shaped the city’s culture.

On a February night in 2004, some 6,000 of New York’s sparkliest turned out to fête the debut of a new celebrity: a 750-foot-tall, two-headed skyscraper clad in dusky glass. Jon Stewart showed up. Cirque du Soleil aerialists writhed, Marc Anthony sashayed, and white-suited waiters distributed mini-BLTs (bacon, lettuce, and truffle). A few guests seemed puzzled to find themselves toasting a shopping mall, even if it was a shopping mall–office building–condo tower–hotel–concert hall combo lording it over Columbus Circle.

To Stephen Ross, the lanky, gravel-voiced real-estate mogul who founded Related Companies and shepherded the building into existence, the opening of the Time Warner Center was the vindication of a $1.7 billion gamble. Two decades in the making, the project spanned four mayoral administrations; weathered a stock-market crash, a major recession, and the 9/11 attacks; and involved an army of architects, deal-makers, functionaries, and lawyers, not to mention the protesters who hoped to stop, or at least shrink it. The Time Warner Center represents the partial triumph of two opposite forces: big-money development and civic activism. The complex accelerated and symbolized New York’s metamorphosis into a high-end consumer product. Within that one building rises a city of $10,000-per-night hotel rooms, $325 dinner menus, and $125,000-a-month rentals. Such imperial prices dramatize the city’s inequities, but the building that some disdained as a fat cat’s bazaar has proven to be — for better or worse — the most influential construction project in New York. The twin-towered complex spawned the row of super-tall condos still popping up along the southern edge of Central Park. If New Yorkers learned to ride escalators in order to buy a fancy shirt or spend too much on lunch (as they now can at Brookfield Place in Battery Park City); if a cultural venue became the ultimate deluxe amenity (as the Whitney Museum and the Shed have gladdened brokers at the High Line and Hudson Yards); if great glass walls came sweeping back into fashion, embodying the glamour of high-rise Manhattan living; and if chefs have become drivers of real estate — all of that is because of the Time Warner Center, too.

At the same time, the building’s story notched a high-water mark for urban activism. In the course of its troubled gestation and complex birth, neighborhood naysayers hung in there so long that they learned to shape the development rather than just opposing it. The Municipal Art Society, a sporadically influential urban-design association dating back to the Progressive Era, together with three adjoining community boards, deployed lawyers, celebrities, and sympathetic editorial writers to decry the project for years. After the first attempt to erect a Columbus Circle colossus failed, one of the gadflies acquired actual power, an MAS member was tapped to design the complex, and advocates helped write the rules for the next go-around. Every development saga also includes its unbuilt alternatives, and the Time Warner Center, with its cool urbanity and high-gloss prisms, and its street-width light well between the two towers, is an immense improvement on what might have been.

The biography of today’s Columbus Circle begins on the day in 1954 when demolition crews showed up to erase a block of 59th Street, taking with them hundreds of homes and stores that Robert Moses had summarily condemned as slums. In their place, he built the New York Coliseum, an ungainly slab of a convention center that reached from 58th to 60th. Moses achieved a miracle of urban renewal: He swept away a poor but functional neighborhood and replaced it with officially sanctioned blight. The Coliseum did its job well enough until 1986, when the Javits Center opened, leaving the never-beloved and now largely vacant hulk to brood over a plaza that was more a chaotic traffic junction than an actual circle. At its nadir, in the late ’80s and early ’90s, the western rim became a more or less permanent homeless encampment. Each Friday night, wives, girlfriends, children, and relatives of convicts gathered in front of the Coliseum to board visitors’ buses for the all-night trip to Attica. Drug dealers hung out on the Central Park side, and whenever a sale was consummated, dashed off to pluck dime bags out of the trees.

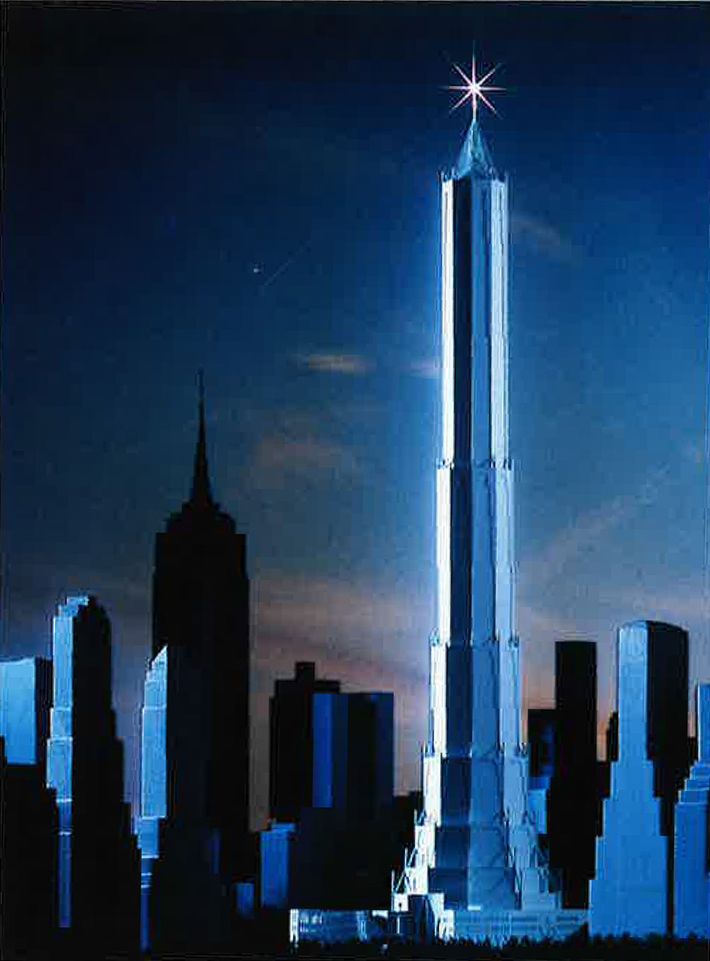

Ironically, it was the prospect of riches that kept the area fallow for so long. The Coliseum belonged to the MTA, which considered the land a potential geyser of cash. In 1987, the agency put out a call for proposals, its parameters calculated to yield the highest price and the biggest building. Among the 13 developers who responded was Donald Trump, who proposed the world’s tallest tower, 137 stories high. Instead, the MTA gravitated to the buyer most likely to pay the most, most quickly, a partnership formed by Boston Properties, founded by Daily News owner Mort Zuckerman, and the bottomless-pocketed Salomon Brothers.

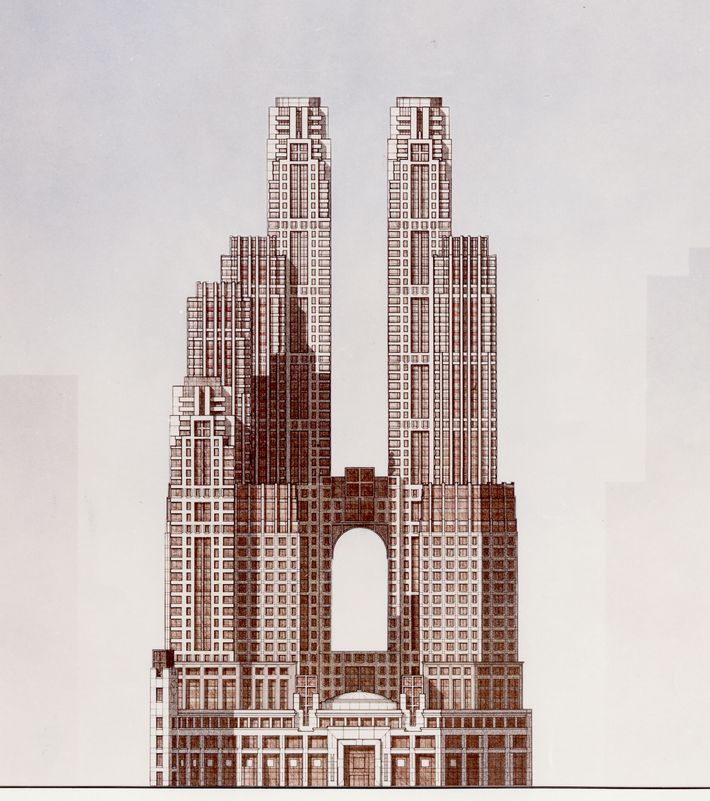

To the hungry transit agency, architecture was an afterthought. To Zuckerman, it was a chance to demonstrate the scale of his ambition. He tapped the famous and flamboyant modernist Moshe Safdie, who took the vast and visible site as an invitation to design a mountain range. He proposed an asymmetrical pair of peaks rising up from jagged shelves, a design whose enormity and disdain for context instantly became a case study in how not to do architecture in New York. The Times’ critic Paul Goldberger wrote that the “gangling composition of anxious angles” had turned the whole project “from vulgar to pathetic.” (Safdie fired back, accusing Goldberger of being a shill for postmodernism.) The problem lay not so much in the aesthetics as in the clotted, airless massing. In retrospect, aspects of the design look prescient. Later skyscrapers — like CookFox’s Bank of America tower, Kohn Pedersen Fox’s Coach Tower at Hudson Yards, and Fox & Fowle’s Reuters Building in Times Square — took up Safdie’s bundles and facets. By contemporary standards, his 900-footer would have been a relatively minor giant, slightly shorter than Christian de Portzamparc’s One57 and a mere splinter compared to the 1,550-foot Nordstrom Tower now under construction on 57th Street. But in the mid-1980s, it seemed like a juggernaut — arrogant and oppressive. The Municipal Art Society and the community boards demanded a shorter, leaner building, one that would ideally restore the through-block of 59th Street that the Coliseum had erased, or at least a generous portion of light and air.

But money and politics have a logic of their own. With Mayor Ed Koch’s blessing, the MTA agreed to sell the Coliseum site to Zuckerman and Salomon Brothers for $455 million (nearly $1 billion in today’s dollars). In February 1987, an arcane (and, as it later turned out, unconstitutional) conclave of city dignitaries called the Board of Estimate held a marathon debate on a foregone conclusion. Joe Rose, the scion of a real-estate family who led one of the community boards, still bristles at the way the developers’ lawyer, John Zuccotti, scoffed at neighborhood and civic concerns. At that stage of the design process, shortening the building was out of the question, Zuccotti said, citing “technical” considerations.

“Name one, John,” Rose demanded. “He answered that mailboxes in the lobby would have to be reconfigured. Mailboxes!”

MAS counterattacked both in the courts and in the press. Recognizing how tough it was to rile up the populace with talk of massing, zoning, and subway bonuses, activists hunted for another tool. Kent Barwick, then–MAS president, recalls a gathering at the Fifth Avenue apartment of Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis, where she looked out of the window and said, “They’re stealing our sky.” That was the clear and present menace that the MAS needed.

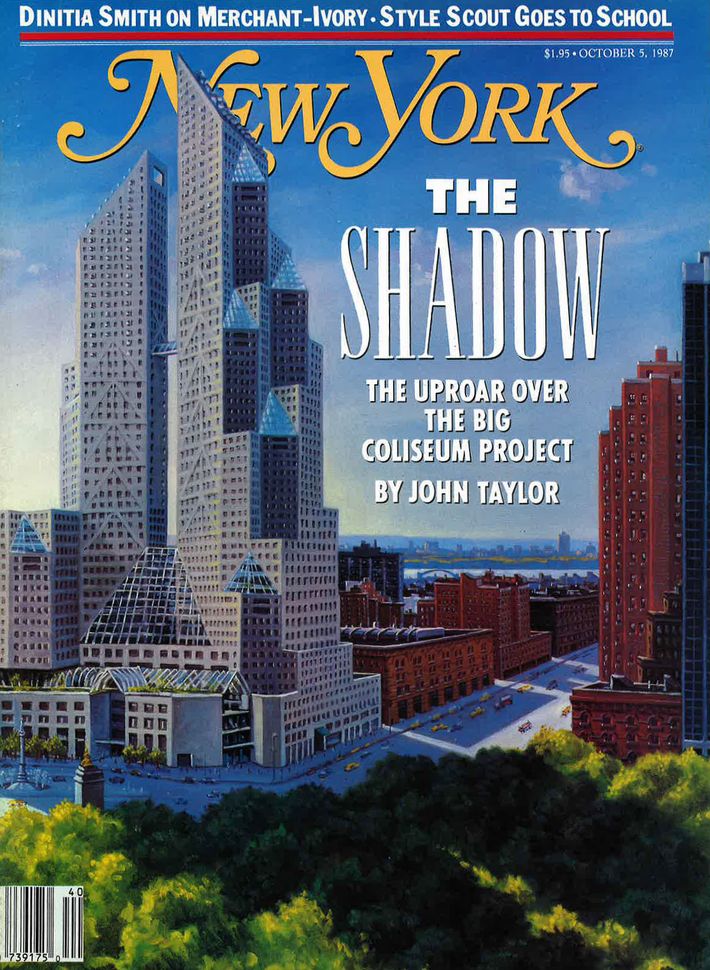

On a warm Sunday that October, about 800 protesters, including Jackie, Bill Moyers, and Paul Newman, marched across Central Park carrying black umbrellas to represent the shadow that Safdie’s tower would cast. New York had prepared their way (and helped summon participants) with an ominous cover story, “The Shadow,” by John Taylor, that opened: “By 5 p.m. in April, it will begin to darken the slides and swings of the Heckscher Playground — darkening, too, of course, the children playing there … In the depths of December, when the reduction in natural light has already put a portion of the population into metabolically induced depression, a stretch of the park almost a mile long … will be plunged into darkness a full half-hour before sunset by the hulking colossus.”

In the end, the shadow had little to do with the outcome, though a coincidence of timing made it look as though the umbrella protest killed the project. The next day, on Monday, October 19, the Dow lost more than 22 percent of its value in a matter of hours — still the worst single trading session in stock-market history. Even before the crash, Salomon Brothers had started retrenching, and by early December, the firm backed out of the deal, leaving Zuckerman to go it alone. Four days later, a judge sided with MAS’s contention that the city had violated its own zoning rules, and he nullified the sale. Koch responded with a shrill threat: “If the project is not built, there will be fewer policemen, fewer sanitation workers, fewer teachers and substantially fewer dollars for transit.”

Zuckerman tried to extricate himself from his financial and legal problems by changing architects. He fired Safdie and replaced him with David Childs, the studiously unshowy star of Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, who produced an overscale memory of Art Deco New York. It didn’t help. With each new version, and each delay, the price for the land fell, from $455 million to $357 million to $338 million. As protests and litigation wore on, MTA executives watched the cash they had hoped for flip away in the breeze and Columbus Circle. In 1994, Zuckerman gave up, allowing a nine-year odyssey to end where it began: with a useless shell flanking a derelict and depressing plaza

All the while, Stephen Ross, the head of Related, was gazing covetously out of his west-facing office window at Madison Avenue and 58th Street. “I looked at the Coliseum all day,” he says. “I became fixated.”

The saga’s second act was in many ways a replay of the first. Once again, the MTA snuffled for cash, a developer had the inside track, and civic groups howled at being left out. This time, though, there was a new sheriff in town. Rudolph Giuliani came onto the scene just as Zuckerman bowed out, and he proved unwilling to rubber-stamp an arrangement that affected such a major Manhattan site. In 1996, the city and the MTA launched a new competition, with slightly more modest criteria: two towers, no taller than 59 stories, rising from a podium that followed the curve of Columbus Circle.

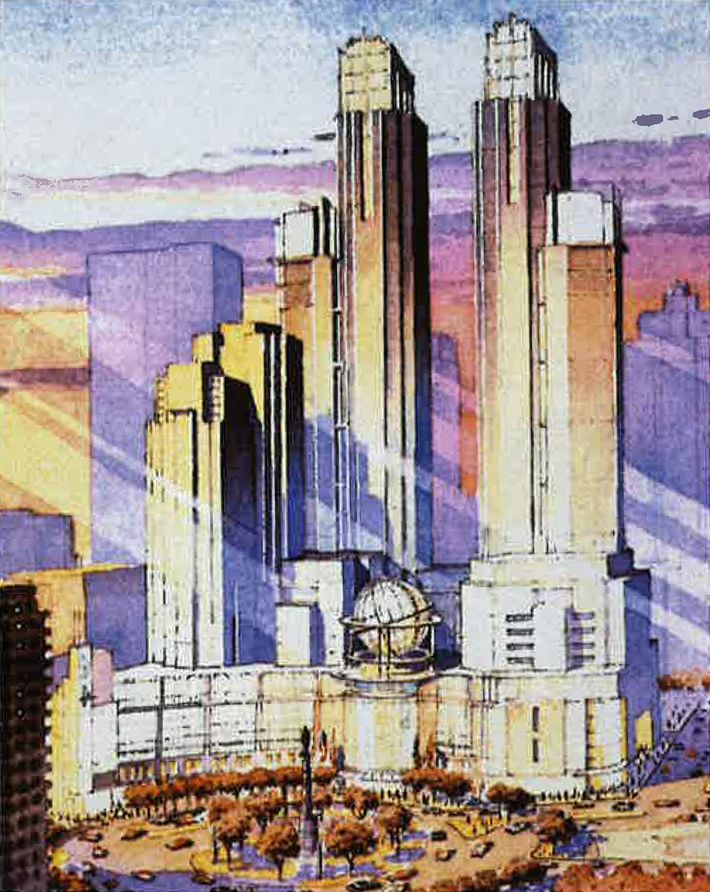

Big names flocked again. Nine development teams submitted proposals: Trump came back, this time with a big masonry block by Robert A.M. Stern and Costas Kondylis. Millennium Partners suggested a big glass slab by Gary Handel and James Polshek. And Ross’s Related Companies got into the game, peddling David Childs’s twin-towered Rockefeller Center redux. Again, critics and the public scrutinized moody drawings and glamorous renderings under the illusion that they were observing a contest among architects rather than gladiatorial combat among moneymen. “You could put the Taj Mahal (from Agra, not Atlantic City) here and it would be lost in the messy maze of hazardous mediocrity that creates no place and answers to no plan,” groused Ada Louise Huxtable in The Wall Street Journal.

Once again, the architecture-blind MTA settled on a preferred developer, Millennium Partners, which was eager to buy the land and start construction, even if there was a lawsuit pending. But the cast of characters had changed. As community-board chair, Joe Rose had stood shoulder to shoulder with the MAS against Zuckerman’s overweening plans; now, as chief of the City Planning Commission, he had the mayor’s ear. On July 26, 1997, Rose was summoned to a Saturday-morning meeting at the East Hampton home of Sandy Lindenbaum, the king of real-estate lawyers. The MTA’s chiefs, including executive director Marc Shaw and chairman Virgil Conway, would be there, anxious to get Giuliani’s sign-off. On the way to the meeting, Rose stopped off to pick up coffee, doughnuts, and a Times — and saw a front-page story proclaiming that negotiations were effectively over and that Millennium had agreed to buy the site for $300 million. The MTA and the developer had leaked the terms to the press, hoping to coerce Giuliani with a fait accompli. When Rose arrived at Lindenbaum’s house, he unfurled the paper and raised an eyebrow. “You don’t force Rudy’s hand like that,” Rose said. A few minutes later, his cell phone rang: It was Giuliani’s deputy, Randy Levine, calling to say that the mayor was quashing the deal.

When Giuliani stepped in, he decreed that an immense structure on a large public site should also include a major cultural component — like, say, a more intimate offshoot of the Metropolitan Opera, the mayor’s favorite arts organization. Soon, he became convinced that a mini-Met could be merged with a home for the fledgling Jazz at Lincoln Center, and he ordered developers to resubmit plans with an auditorium. Ross used the time efficiently. Eager to fill the office space and recruit an investment partner, he courted Richard Parsons, the CEO of Time Warner. “It’s not about office space; it’s about showcasing the largest entertainment company in the world,” Ross told him, mixing flattery with argument. Parsons agreed to buy more than 1 million square feet in one of the new towers and build studios for CNN.

Ross recalls that when he entered the scrum for the Coliseum site, he felt his competitors were too timid, overly sensitive to a real-estate market still struggling to emerge from the early 1990s slump. “They were looking at what the economics could afford at the time,” Ross recalls. “The predominant use they had in mind was a convention center — hotel, with maybe some condos and rentals: very pedestrian. I saw it as a world-class site.” Ross’s ambitions matched Giuliani’s: both envisioned Columbus Circle as the hot core of a thriving city, the sort of indoor habitat where affluent New Yorkers and visitors might one day go to work, listen to music, have dinner, get a massage, and shop, all under one roof. With Time Warner in his pocket and a newfound love for jazz on his sleeve, Ross lobbied the city hard.

On July 27, 1998, exactly a year after the East Hampton fiasco, he landed the great whale. Related paid $345 million for the site — more than Millennium Partners would have paid the previous summer, but much less than the sum that Zuckerman had promised a decade earlier. Now, Related just needed to come up with a workable design for 2.5 million square feet — and the money to build it.

Childs was proud of his plan to evoke the vanished block of 59th Street by projecting it into the sky, pushing apart the two towers by the width of a city street. “David kept walking around the office with his fingers in a V to show the separation,” says T.J. Gottesdiener, now SOM’s managing partner. With each successive iteration, Childs simplified the design, finally distilling it to a pair of prismatic towers aligned with the diagonal of Broadway and aslant Manhattan’s rectilinear grid. The glass virtuoso James Carpenter used slender steel cables to suspend an ultraclear wall — then the largest of its kind — that seemed to float like a soap bubble between the shops and the street. Its exterior simplicity hid what Childs calls the “Chinese puzzle” within. SOM’s architects had to figure out how to get food to the restaurants, pianos to the rehearsal rooms, audiences to the auditorium, hotel guests to a sky lobby check-in, CNN reporters to the newsroom, and shoppers to the upper levels of a vertical mall, all without choke points or traffic jams. The marquee tenants all demanded visible presences on the street. Gottesdiener recalls that negotiating among five separate factions turned architecture into a combination of shuttle diplomacy and family therapy. Whenever the process stalled, Ross arbitrated. “Steve was Solomon,” Gottesdiener says.

Though large-scale mixed-use complexes are fairly common in Asia, they are both rare and risky in this country, where a combination of zoning restrictions, land costs, lending practices, and the real-estate market favor more straightforward divisions. To succeed, the Time Warner Center’s economic structure would have to rest on a foundation of shopping. In a city of sidewalk shoppers, a vertical mall looked like heresy — Trump Tower provided a miniature example and Manhattan Mall a failing one; Ross and his partner, former restaurant owner Kenneth Himmel decided that the only magnet powerful enough to draw visitors up all of those escalators was food. They dreamed of destination restaurants that would turn Columbus Circle into a foodie mecca, and so Himmel went hunting for chefs.

At the top of his list was Thomas Keller, who had abandoned New York in the early 1990s and become a superstar with the Napa Valley pilgrimage spot French Laundry. Ross and Himmel flew out to California for lunch and laid down a royal flush of incentives: a glamorous Manhattan view, a chance for Keller to pick his neighbors, and all the start-up money he could use. Soon after, Keller visited the construction site, paced the wind-battered concrete slab, looked down Central Park South shooting eastward from his future dining room window, and said an enthusiastic yes!

Next, Himmel focused on the basement. Today, the fusion of development and high-end groceries seems obvious: Le District at Brookfield Place and ever-more-deluxe Chelsea Market at the High Line lure tenants with a deluxe food court. Back then, though, Ross was uneasy about tucking a supermarket underground, fearing rats and a déclassé clientele. Himmel insisted that Whole Foods executives go on a grand tour of European food temples like Fauchon and Harrods and return with a plan for the country’s fanciest market. Just to make sure, the lease gave Related final approval over the store’s design. Today, the Columbus Circle Whole Foods sells about $100 million worth of groceries a year. Even at midtown prices, that’s a lot of organic millet.

Related had agreed to find room for a 1,000-seat auditorium for Jazz at Lincoln Center, but once design got underway in earnest, the developer and the music-group arm fought over every detail. To Ross, every square foot he gave away for free cut into his calculations and increased his risk. The developer and the nonprofit fought over location, loading docks, and marquee placement. In retrospect, Ross might have relaxed. During the ’50s and ’60s, when Lincoln Center was conceived, city leaders believed that culture needed its own clearly bordered campus, set off from the neighborhood jangle. Ensconcing a large concert hall in a residential development would have seemed downright weird. More recently — partly thanks to the experience with Jazz at Lincoln Center — developers have learned to think of cultural facilities as amenities. The Whitney has turbocharged the High Line area, and the World Trade Center will eventually get its Ronald O. Perelman Performing Arts Center. At Hudson Yards, Ross is enthusiastically supporting the Shed and eager to spend $200 million on a sculptural basket of staircases to nowhere designed by Thomas Heatherwick. Art pays.

But in the 1990s, Jazz at Lincoln Center, a start-up with a skinny budget, was the David to Ross’s Goliath, armed with a few high-powered weapons. One was Wynton Marsalis, the organization’s deceptively easygoing artistic director, who framed the moral argument that America’s music needed a home of its own. The second was Parsons, the Time Warner CEO, who loved jazz and talked Ross out of stashing the hall in a basement or out back. And then there was Rafael Viñoly, one of the few architects with the clout to go mano a mano with Childs. He figured out how to isolate the auditorium acoustically, cushioning it with rubber dampers like a sensitive instrument packed in a shipping crate. He also managed to satisfy both Marsalis’s desires for the ultimate jazz headquarters and Giuliani’s demands for a hall that could accommodate opera, too. It was Viñoly who came up with the idea of tucking a more intimate cabaret-style space, the Allen Room (recently redubbed the Appel Room) up against the building’s glass wall, so that an art form born on the street could now look down on it from above.

The auditorium’s costs ballooned from an original estimate of about $40 million to a final tab of $131 million. “When that opportunity came along, it was a blessing and a curse,” Marsalis says. “We had to leap at it, but it would put tremendous strain on us. We had no idea how tremendous.” At first, the job of scaring up that fortune fell to board chairman and financier Ted Ammon. But in October 2001, in a plot twist that turned fundraising into a thriller, Ammon was bludgeoned to death in his East Hampton home by his wife’s lover (and probably by his wife, Generosa, though she died before she could stand trial). The chair passed to the only woman in this epic’s cast of characters: Lisa Schiff, who turned a partnership with Marsalis into a relentless dollar-scooping machine. “People would see us coming and run,” she recalls. Tempers ran so high and sleep grew so scarce that on one occasion, Schiff and Marsalis found themselves together in a car on their way to a meeting, and suddenly realized that neither had any idea who they were going to see.

They were not the only ones scrounging. The term “real estate” sounds solid and sober, but there’s an awful lot of flimflam and fantasy along the way to the ribbon-cutting. Convincing banks to gamble on Ross’s untested formula for a mixed-use complex required him to do some pretty fancy hustling. In the wake of the 2000 Nasdaq crash, he made the rounds of all of the usual lenders and found them too cautious and distressed to help. Retail tenants were waiting for the project to be real, and bankers were waiting for tenants. Somehow Ross convinced GMAC that other lenders were competing for a piece of the deal, and the company scattered its fictitious competitors by slapping $1.3 billion on the table — the largest construction loan ever.

Six weeks later, terrorists brought down the World Trade Center, making the world doubt whether anyone would want to live or work in a high-rise ever again. Over the summer, buyers had taken the first step in snapping up dozens of condo apartments — or rather unenclosed patches of sky that would one day metamorphose into apartments. After 9/11, those customers scattered. “We had 70 contracts out at the end of August,” Ross says. “We didn’t get a single contract back.” Though it was too late to halt construction, Related shut down its sales office and pulled the condos off the market for a year. Disasters continued to occur at a regular clip, including a couple of fatal construction accidents and a fire that broke out near the entrance to the jazz hall in April 2003, a week before Passover. Lisa Schiff asked herself, “I said: What about the pestilence? Are we getting that, too?”

Despite the glittering debut in 2004, Time Warner Center actually opened in stutter steps. Two weeks after Per Se opened, another fire destroyed the kitchen, and a despairing Keller had to be talked out of breaking his lease. When the restaurant reopened six months later, New York’s Adam Platt greeted it with a slightly suspicious rave. It was, he wrote, “a studious California version of what a first-class New York restaurant should be.” The magazine’s then–architecture critic, Joseph Giovannini, was more dyspeptic. In a review larded with words like “uneasy,” “fussy,” and “disappointing,” Giovannini wrote that “sometime after the conceptual stages, SOM suffered a failure of attention span” — a brutal swipe at a project that Childs had worked on for nearly two decades.

Fourteen years after its opening, the Time Warner Center is still riddled with compromises. Taking an elevator to a concert feels like a cold, corporate prelude to an evening of music. The shops have the anywhere feel of an upscale airport concourse. Restaurants turn inward rather than adding to the buzz. The condos have helped make New York a magnet for foreign plutocrats eager to alchemize dubious fortunes into solid square footage. You might see the Time Warner Center as the epicenter of the city’s spreading generic luxury.

And yet the building has proven both successful and influential. Childs’s design knitted together midtown and the Upper West Side, turned a desolate Columbus Circle into a destination, and rejuvenated the southwest corner of Central Park — all goals that the MAS and its partners did battle for. It also helped shift the city’s center of gravity westward, completing a media corridor that runs from Times Square past the Hearst Tower, to CNN. Even “The Shadow” spends much of its time tucked, more or less inoffensively, behind the Trump International Hotel and Tower. Unlike the hypertall and skinny condo towers it spawned, the Time Warner Center is constantly full of both visitors and New Yorkers, its liveliness spilling out into the street.

Perhaps the building’s longest-lasting legacy will be as a forerunner for Related’s even more super-mega-giant development: Hudson Yards. There, instead of components packing into a single container, they will spread out over an entire mutant neighborhood. Sometime next year, Time Warner, the company, will abandon Columbus Circle and relocate to Hudson Yards, which will boast more of everything: shops, restaurants, and offices, plus a vaster plaza, a bigger cultural center (the Shed), Heatherwick’s outsize folly, and much, much more money at stake. Ross is no doubt planning an opening-night party that will make the last one look like a high-school dance.