One of the most abiding memories of my early childhood is of a Saturday night when my father was settling into his recliner to watch a movie (this was back when relatively recent movies on TV were a rare treat) he had long anticipated seeing. Just as it was about to begin, his mother, my paternal grandmother, who happened to be visiting, got up, changed the channel, and intoned: “It’s time for Billy Graham!”

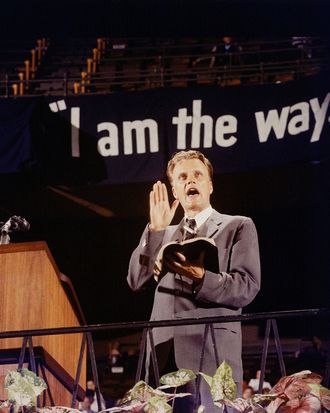

This was doubtless an experience shared widely in and beyond Graham’s native South. Graham’s frequently televised “crusades” (as he called his public evangelistic events until 9/11, when the connotations in the Middle East became newly salient) became a regular part of American life from the 1950s on, presenting an intensely personal but ecumenical version of evangelical Protestant Christianity to a rapidly secularizing world. Suffering from a variety of ailments, Graham had been out of the public eye since his last big preaching event in 2005 (in Flushing Meadows, as it happens). Upon his death today at the age of 99, his legacy as perhaps the first global evangelist, and certainly the first televangelist, is secure. But his relationship with the politically powerful, which in some respects anticipated the Christian right (which Graham himself conspicuously did not join), provides a more complicated picture.

As brilliantly explained in Darren Dochuk’s 2012 book, From Bible Belt to Sunbelt (which features a photo of a young, crusading Billy Graham on its cover), Graham led a whole generation of evangelical preachers and institution builders who combined “old-time religion” with modern technologies and organizational techniques, and made common cause with political conservatives on a host of contemporary issues. It was fitting that his national emergence occurred after a 1949 “crusade” in Southern California (promoted avidly by the Hearst press thanks to his aggressive anti-communism), the great melting pot of political, economic, and cultural trends that largely created modern American conservatism. Graham was also influential in his relatively early repudiation of Jim Crow, which had long created an obstacle to the spread of both Southern-style religion and politics.

Graham met his first president in 1950, when a friendly congressman took him to see Harry Truman. Graham’s growing celebrity and instinct for the main chance quickly led to his reputation as “Pastor to the Presidents,” and he was consulted by Eisenhower and (despite Graham’s initial ambivalence about a Catholic president) Kennedy, before his closest political associate, Richard Nixon, entered the White House.

Graham clearly gloried in his tight relationship with Nixon, who benefited significantly from his association with the revered evangelist (it certainly fit in nicely with his “Southern strategy”). And it is reasonably clear that Nixon’s disgrace (and the exposure of his somewhat less than Christian views on many subjects) became a cautionary tale for Graham the rest of his life. Yes, he still “pastored” presidents on demand, but he became wary of partisan politics, avoiding political controversies and associating too closely with politicians. Interestingly, this anti-political evolution by Graham coincided roughly with the birth of the Christian right, when so many of the evangelical leaders he profoundly influenced formed a movement that eventually became a key constituency group of the Republican Party.

Another aspect of Graham’s ministry also increasingly separated him from many of his natural allies— notably those in the Southern Baptist denomination in which he was baptized and ordained. While he was always a Biblical literalist — his sermons invariably drew on a very straightforward interpretation of the Bible — he eschewed denominations and theological litmus tests, and found common ground with those liberal Christians that today’s conservative evangelicals dismiss and despise for their rejection of Biblical literalism and culture-war causes like abortion and “traditional marriage.” Graham often broke bread with non-Christians as well.

If Graham’s legacy is in any danger of drifting away from his strategy of making “a decision for Christ” convenient both physically and emotionally for people from all sorts of backgrounds, it is probably due to the growing shadow being cast by his son and successor, Franklin Graham. The younger Graham took over his father’s main ministry in 2001, not long after taking on his father’s traditional role of praying at presidential inaugurations (Franklin’s prayer for George W. Bush stirred up controversy for its exclusivist Christian terminology). The younger Graham very quickly erased the ground that had separated his father from the Christian right, becoming an enthusiast for the Iraq War, an Islamophobe, and an increasingly active participant in political controversy.

A key moment in the transition from one Graham to the other occurred in 2012, when on the eve of an intensely fought battle over a proposed constitutional amendment in North Carolina to ban same-sex marriage, full-page ads appeared over the then-93-year-old Billy Graham’s signature endorsing the discriminatory measure. As I commented at the time:

[W]hy, at this late stage of his life, when he had finally achieved a reputation as a religious leader who had transcended all the divisions of his times, would he so conspicuously enlist in the shopwarn anti-gay-marriage cause, in his home state no less? It’s hard to say, unless he’s no longer in control of his ministry or of his faculties. But it’s sad to see; sort of like an aging musician who courts embarrassment with just one tour too many instead of letting the old recordings speak for themselves.

We have no way of knowing what Billy Graham might have thought of his son’s steady path into partisan politics, crowned by his emergence as a prominent supporter and apologist for Donald Trump, a figure who exceeds even Nixon as a morally perilous object of evangelical adoration.

Now that Billy Graham’s gone, his many admirers can only hope that his true legacy is in the quiet moments of self-reflection and spiritual discovery he inspired in many millions of people, for whom his version of old-time religion offered all-encompassing love, not self-righteous hate. But his long career at the crossroads of religion, popular culture, and politics is a reminder of how hard it is to distinguish the power of God from the God of power.