Last night in Sunrise, Florida, the unthinkable happened: CNN provided its audience with riveting — and civically productive — prime-time programming.

In the United States, elected officials answer, on a near daily basis, to the big-dollar donors who fund their campaigns — and almost never to the constituents who suffer most from their policies. But for two hours at the BB&T Center, a Republican senator and an NRA spokesperson were forced to explain themselves to the victims of the gun violence that they had abetted. For one night, politics ceased to be a low-stakes parlor game; “tough questions” stopped serving as occasions for congressmen to showcase their skills at verbal tap-dancing. Marco Rubio had to stare into the face of a survivor of the shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School, and explain why he would gladly accept more money from the NRA. For progressives, the spectacle was thrilling, uplifting, and cathartic.

But it was also, intermittently, disconcerting.

Much of Wednesday night’s discussion proceeded from the premise that American schools are exceptionally unsafe places, and that mass shootings are a top-tier threat to the lives of America’s young people. Neither of these assertions is true.

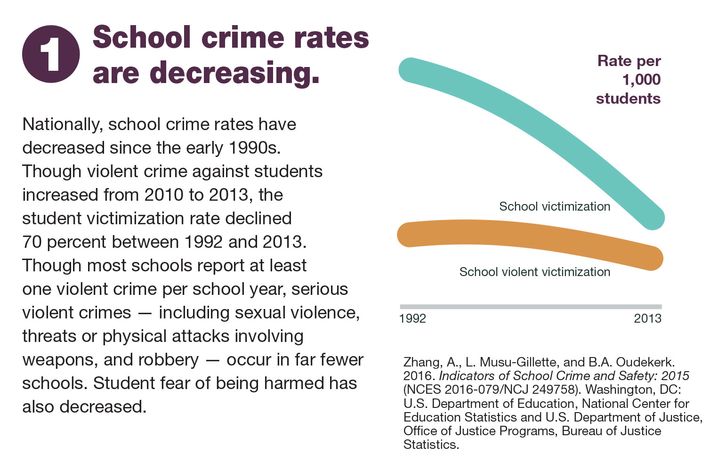

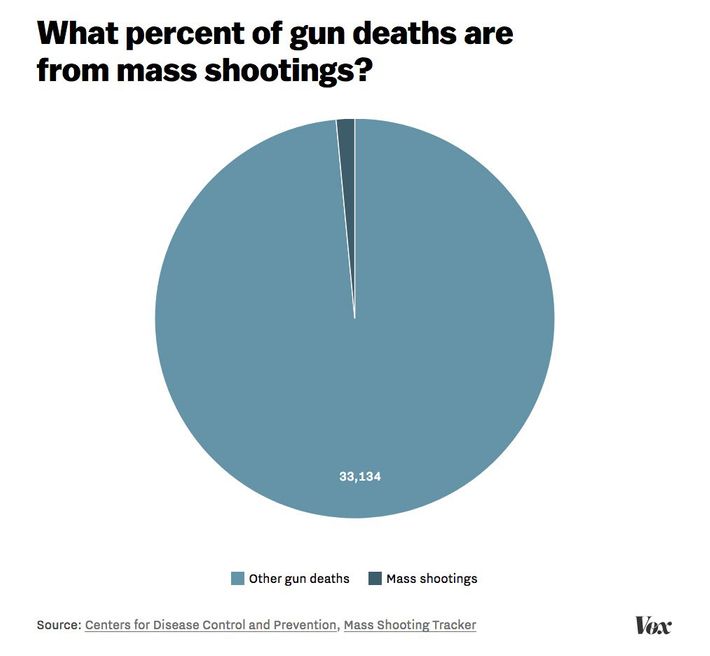

Schools in the United States are safer today than at any time in recent memory. Criminal victimization in America’s education facilities has declined in tandem with the nation’s collapsing crime rate. Meanwhile, as of 2013, the year after the Newtown massacre, mass shootings accounted for only 1.5 percent of all gun deaths in the United States, or 502 total fatalities. That figure is unacceptably high. But it nonetheless represents a minuscule portion of our overall gun problem, and a tiny fraction of the lives lost each year to countless other social crises, from the opioid epidemic, to workplace safety violations, to the unaffordability of health insurance.

When protesters and pundits elide these realities while advocating for life-saving gun restrictions, it’s hard for liberals to object. The cable news media simply isn’t interested in treating America’s epidemic of firearm suicides or urban gun violence as headline news. The lurid spectacle of mass shootings concentrates national attention on our gun violence crisis like nothing else does. So, there is a strong tactical temptation to exaggerate the prevalence of such events. In the wake of the Parkland shooting, progressive activists and commentators (including this one) repeatedly claimed that there had been 18 school shootings since the start of this year. When the Washington Post looked into that statistic — and found that it included a suicide in the parking lot of a long-closed elementary school, and that there had only been five incidents that resemble the popular understanding of a “school shooting” — some progressives mocked the paper for its callous pedantry.

This sort of response struck me as defensible — until the victims at CNN’s town hall began using the supposed ubiquity of school shootings as a justification for policies other than gun control.

Last night in Sunrise, Lori Alhadeff, mother of one of the teenagers killed in last week’s atrocity, demanded to know why Congress hadn’t responded to the Newtown massacre — by turning every school into an armed fortress:

In 2013, the NRA released a 225 page report to call for more security at schools. It detailed security guards, teacher training, bomb sniffing dogs, expanded police presence in schools. Here we are five years later and nothing has been done. Our teachers need to be properly trained to teach our children how to handle a code red. We can visually mark hiding areas in the classrooms to protect our children from being gunned down.

Where are our metal detectors? Where is our bullet proof glass?

One student survivor of the Parkland shooting echoed this line of thought, asking, “Why don’t we have Kevlar vests in classrooms for our students? Why don’t we build our walls with Kevlar so that kids aren’t being shot through their own walls because they’re so cheaply built?”

Shortly thereafter, Broward County Sheriff Scott Israel called on Congress to expand the power of law enforcement agents to unilaterally commit mentally ill suspects to psychiatric facilities.

If the bulk of America’s 30,000 annual gun deaths were the product of mentally ill people shooting up schools — as some media coverage and political rhetoric would lead one to believe — there might be a rational case for these measures. But such events account for an infinitesimal fraction of American gun deaths; and from a progressive perspective, the downsides of these proposals are massive.

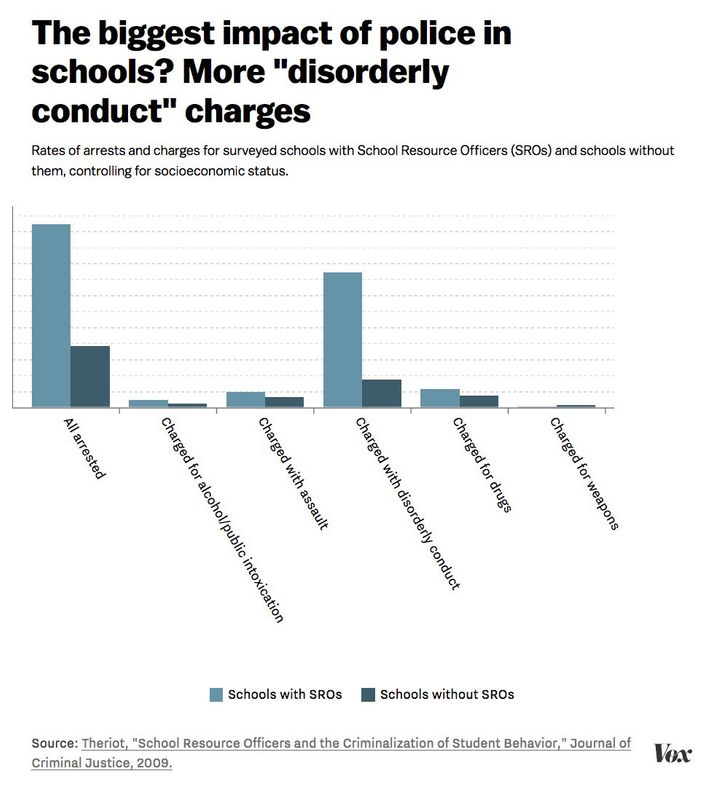

The best available research suggests that putting police officers in schools does not significantly deter crime on campus — but does increase the number of students who end up incarcerated for minor youthful indiscretions. As Vox’s Dara Lind writes:

A 2009 study by Matthew Theriot of the University of Tennessee compared student arrest and court records from one group of schools that had a school resource officer stationed on school grounds with those of schools that didn’t. Controlling for socioeconomic status, the researcher found that there wasn’t much difference in serious crime between the schools that had SROs and the schools that didn’t. Students at policed schools were much more likely to get arrested than students at unpoliced schools, but they weren’t any more likely to actually be charged in court for weapons, drugs, alcohol, or assault. (In other words, students at policed schools were much more likely to get arrested in cases where there wasn’t enough evidence to actually charge them with a crime.)

The exception: Students at policed schools were almost five times as likely to face criminal charges for “disorderly conduct” (which apparently didn’t rise to the level of an assault). In other words, when there was a police officer roaming the halls, students were much more likely to be arrested and brought into court for behavior that was disruptive, but not violent.

There is a real risk that by exaggerating the prevalence of school shootings, progressives could abet an expansion in our nation’s (already scandalously high) juvenile incarceration rate. As of this writing, the only direct policy response to the shooting in Parkland has been an increase in the number of rifle-carrying sheriff’s deputies on the grounds of Broward County’s public schools.

The downside risks of installing metal detectors at all schools – or lining their walls with Kevlar — might be less grave. But America’s schools don’t have a whole lot of surplus funds to waste on security theater. Last month in Baltimore, students shivered their way through classes held in schools without heat.

Meanwhile, the hazards of making it easier for police to involuntarily commit the mentally ill to in-patient facilities should be obvious. In my view, there is a reasonable (though, not necessarily convincing) case for restricting the ability of the severely ill to purchase firearms — not because such individuals are especially likely to commit homicide (they aren’t), but rather, because more than half of all gun deaths in the United States are the result of firearm suicides. And a wide range of mental illnesses increase a person’s risk of suicidal ideation.

But the notion that mental illness renders a person exceptionally likely to commit mass violence is a dangerous fiction, one that could exacerbate our country’s already-calamitous tendency to criminalize psychological distress.

All of which is to say: The politics of mass shootings have real perils for progressives. Even more mundane and mainstream policy responses — like stiffening sentences for existing gun crimes — threaten core left-wing objectives, such as ending mass incarceration. Generally speaking, the left and its ideals do not thrive when voters fear for their physical safety.

There have been signs that gun control advocates — not least, the heroic teenage protesters of Parkland — are capable of keeping the political conversation from veering off into ill-advised directions. The crowd at CNN’s town hall last night evinced zero tolerance for the president’s preposterous proposal to arm teachers. And yet, that audience was decidedly more receptive to the idea of packing schools with armed police, or criminalizing against the mentally ill.

So, as the (vital) debate over gun violence proceeds, progressives must remain as vocal in their opposition to counterproductive and authoritarian policy responses as they’ve been to the prospect of no policy response at all.