Nine years ago today, America’s unemployment rate was 8.1 percent and rising. Credit was scarce; private-sector investment, as tepid as consumer demand. Mainstream economists broadly agreed that massive government stimulus was required to avert a potential depression. And the Republican Party decried a package of deficit-financed spending increases and tax cuts — one that was far smaller than most experts thought necessary — as a “worldwide borrowing binge” that would put America “on the road to stagflation.”

Now, our nation’s unemployment rate is at a 16-year low. Corporate profits are near record highs. Mainstream economists broadly agree that no fiscal stimulus is necessary — and Republicans are on the cusp of following a giant, deficit-financed tax cut with a package of deficit-financed spending increases. Taken together, these bills could add up to a stimulus larger than Barack Obama’s American Recovery and Reinvestment Act. As Jim Tankersley of the New York Times explains:

The $1.5 trillion tax cut that President Trump signed into law late last year, combined with a looming agreement to increase federal spending by hundreds of billions of dollars, would deliver a larger short-term fiscal boost than President Barack Obama and Democrats packed into their $835 billion stimulus package in the Great Recession.

… The Republican tax law’s $1.5 trillion deficit-financed price tag over the next decade is front-loaded. It will reduce federal revenue by $416 billion over this year and next, before accounting for additional economic growth, the Joint Committee on Taxation estimates…The likely spending increases include money for the military, domestic programs and disaster aid, along with a plan to shore up faltering multiemployer pension plans. The Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget estimates that those increases will cost more than $500 billion, and that congressional negotiators are mulling roughly $100 billion in revenue increases to offset them, yielding a deficit increase of $400 billion.

One could put some caveats on this analysis. As a percentage of GDP, Obama’s stimulus was still larger than Trump’s would be. And Republicans aren’t pushing deficit-financed spending increases entirely of their own volition: The GOP needs Democratic help to increase military spending, and the price of that assistance is higher domestic spending, along with significant relief funds for the victims of last year’s hurricanes.

Nevertheless, the fundamental point remains: Republicans are pursuing an economic policy that is mind-boggling hypocritical – and, in the estimation of most economists, profoundly irresponsible.

And, all things considered, that’s probably a good thing.

Stimulating an already-strong economy comes with real risks. Beyond growing the deficit, such a policy can produce too-high inflation, which can lead to higher interest rates — and thus, higher borrowing costs for the government. This can potentially limit long-run growth, and, more critically, restrict the government’s capacity to juice the economy during the next downturn.

But turning up the temperature on a hot economy also has its benefits: Since workers at the bottom of the economic ladder only enjoy significant wage gains in the very tightest of labor markets, there are few better policies for growing the paychecks of the working poor, and narrowing inequality, than full employment. And achieving full employment in our current moment likely requires a bit more stimulus.

In my view, it is hard to see how the deficit and inflation are bigger problems for the U.S. economy circa 2018 than inadequate wage growth. Inflation is still below the Federal Reserve’s target of 2 percent — and that target is itself rather low. America’s public-sector debt is getting large — but still not that large. Right now, our government debt is equal to 106 percent of our gross domestic product (GDP). Japan, meanwhile, has government debt equal to 238 percent of GDP. And while that country’s economy has problems, they aren’t the ones that deficit hawks warn about: Japan has the opposite of an inflation crisis, and has no difficulty finding investors for its bonds.

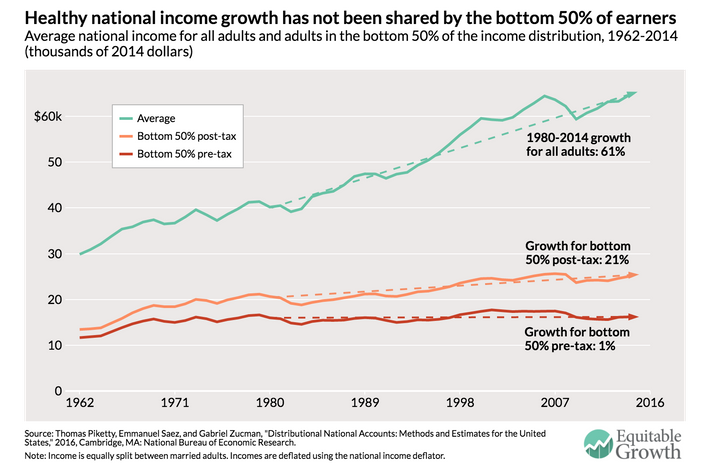

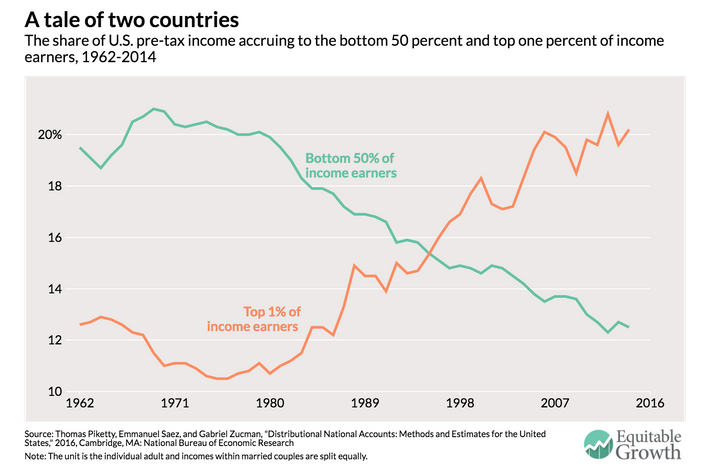

By contrast, the bottom half of American workers have gone without a significant raise for nearly six decades now — and their share of national income has plummeted in the process.

What’s more, while mainstream economists believe that running the economy even hotter will deliver no benefits to long-term growth, there’s reason to suspect otherwise. Recently published research from the Roosevelt Institute suggests that super-tight labor markets might be the key to increasing productivity — employers are reluctant to innovate unless rising labor costs force them to search for new efficiencies.

Ultimately, “responsible” fiscal policy is in the eye of the beholder. Creditors have much more to lose from inflation than debtors do, while the independent contractors in Amazon’s warehouses have much more to gain from a 3 percent unemployment rate than Jeff Bezos does. When one considers the balance of present risks, the progressive case for further stimulus looks strong.

Or, at least, it looks strong from a purely economic perspective, anyway. Once one considers the political variables, the picture becomes more complicated. If one believes that the GOP’s congressional majorities pose an immediate threat to the poor, the climate, and potentially our democracy — and that Trump’s judicial appointees pose a long-term threat to all three — then an economic policy aimed at maximizing wage growth right before the 2018 midterms may seem inadvisable.

More fundamentally, even if Trump’s stimulus doesn’t preclude an effective response to the next recession for economic reasons, it could still do so for political ones. When and if Democrats regain power, Republicans are sure to rediscover their devotion to fiscal probity —and this president’s spendthrift ways will help them make the case against an adequate stimulus package and/or new spending on progressive priorities (just as Bush’s did in 2009).

That said, if progressives wish to effectively counter such appeals to deficit-phobia in the future, they should avoid making them in the present.