The Democratic Party has never been more reliant on the support of upper-middle-class voters than it is today. And the economic fortunes of affluent Americans — and those of the typical working-class household — have rarely been more disparate. These twin developments have inspired much commentary about the class tensions beneath Team Blue’s “big tent” — with many progressive pundits worrying that the party’s growing dependence on the votes of comfortable professionals could render it incapable of mounting an adequate response to runaway inequality.

That fear has a basis in reality. As the American labor movement declined over the second half of the 20th century — and many white working-class voters lost their attachment to the Democrats (and/or to voting, at all) — the party began courting upper-middle-class voters more aggressively, and its center of gravity on economic policy shifted rightward. Although many other factors shaped the party’s path from the “War on Poverty” to “Welfare Reform,” there’s reason to believe that the shifting socioeconomic composition of its voting base was a significant one: The economist Thomas Piketty has demonstrated that left-wing parties in Britain and France experienced a very similar transformation during the same period — their voting bases grew more affluent and highly educated, and their economic platforms simultaneously became less progressive.

For this and other reasons, there is little doubt that it would be easier to advance radical economic reform in an America where politics was sharply polarized along class lines, and working people of all races were concentrated in a single partisan coalition.

But that doesn’t mean that the Democratic Party cannot advance significant progressive change in the America we live in now.

It is absolutely true that a liberal software developer in Williamsburg and the delivery person who brings her Seamless have different class interests. And as Thomas Edsall notes in his New York Times column this week, America’s urban housing crisis is making those disparate interests more apparent: Many upper-middle-class Democrats own homes in metropolitan areas, and thus, directly benefit from both housing scarcity and gentrification; many working-class Democrats, meanwhile, are being displaced by those same forces. The fact that these constituencies share a party makes a radical response to the latter’s plight — like, say, a steep land-value tax that renders urban housing undesirable as an investment asset (thereby triggering a massive plunge in home prices) — politically unthinkable.

But in dwelling on this reality, Edsall arrives at an unjustifiably dire conclusion about the Democratic Party’s capacity to implement progressive policy: The columnist suggests that the Democrats have become beholden to a “well-educated elite” that “is not friendly to redistribution, because it believes in meritocracy” — and thus, that the party will be unable (and/or unwilling) to effectively address “the economic interests of those in the bottom half of the income distribution,” until the Trumpen proletariat attains class consciousness and moves back into the Democratic fold (a development that he does not characterize as very likely).

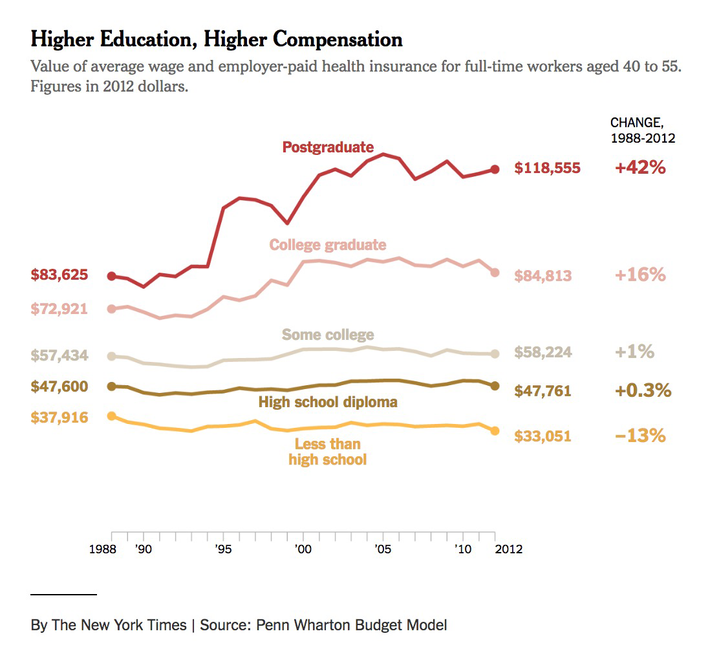

There are (at least) three problems with this analysis. First, it overestimates the degree to which narrow self-interest determines policy preferences. Material interest is undoubtedly a powerful political force — but so is group identity. As Edsall notes, college-educated Americans have been claiming a growing share of our nation’s pre-tax income:

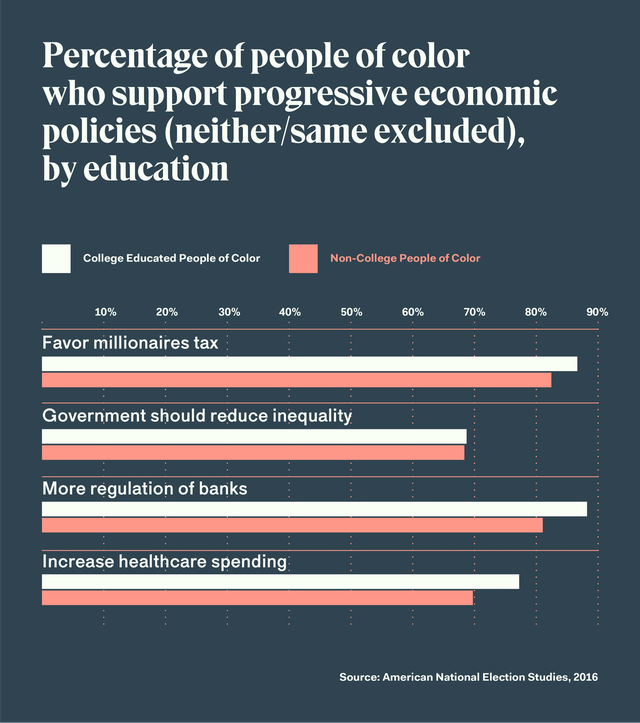

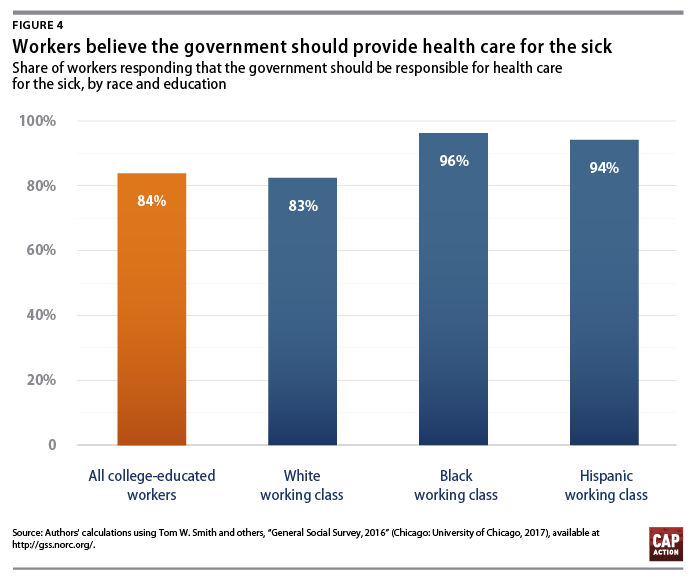

And yet, support for progressively redistributing that income through government programs is higher among nonwhite college graduates than it is among the nonwhite working class.

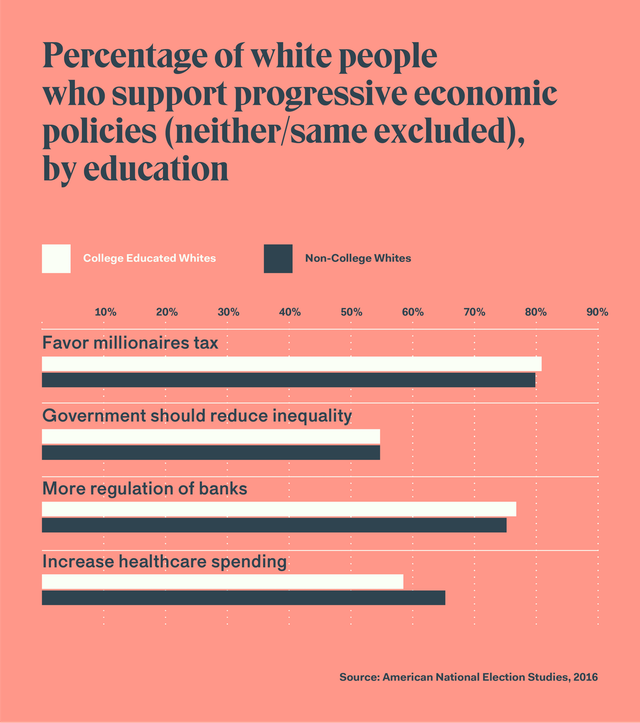

And the same is true among white voters on every issue listed above except for health-care spending (and even there, a majority of college-educated whites support increased federal investment):

To be sure: A college education is not a perfect proxy for socioeconomic class. And, as we’ve already seen, the class interests of affluent Democrats can act as a constraint on progressive policy when the latter threatens the former in an especially visceral fashion — as when Barack Obama tried to roll back tax benefits on 529 college-savings accounts. There’s little doubt that a Democratic Party composed entirely of voters in the bottom 80 percent of the income distribution would have an easier time rolling back regressive, upper-middle-class welfare spending (by, for example, taking all of the revenue the government loses on the mortgage interest deduction and plowing it into public housing and means-tested rent subsidies).

Nevertheless, there is little evidence that affluent Democrats are violently opposed to paying modestly higher taxes for the sake of fortifying America’s social safety net (as research from the Center for American Progress Action has demonstrated).

The second flaw with Edsall’s analysis is that it underplays the degree to which ideas can exert an independent influence on partisan policy-making. The vast majority of voters, of all classes, pay relatively little attention to the finer details of public policy — and take most of their ideological cues from the leadership of their preferred political party. Thus, elite policy wonks and politicians have a good deal of flexibility in defining what, precisely, a center-left economic agenda means at any given moment in time.

In the wake of the Great Recession — and lackluster recovery — the economic thinking of the Democratic Party’s Establishment intellectuals has moved dramatically leftward. By all appearances, this shift has not been driven by any change in the material interests of center-left policy wonks, as a class, but rather, in changes in empirical reality. Put simply: It is very hard for an intellectually honest economist to look at America in 2018 and conclude that massive redistribution is not urgently needed.

Since 2016, the Center for American Progress — the Democratic Party’s Establishment think tank — has released proposals for a federal job guarantee, a universal health-care plan (that’s in the general vicinity of single-payer), and wage boards to facilitate industrywide collective bargaining for private-sector workers. Meanwhile, the party’s top presidential prospects have been racing to pledge their allegiance to socialized medicine, free public college, universal child care, and paid family leave. And on the state level, Democratic lawmakers in New York and California — who very much rely on the support of upper middle-class voters — have already implemented a wide variety of redistributive social programs.

The final — and perhaps, most significant — flaw in Edsall’s analysis is that, in fixating on the disparate material interests of affluent Democrats and working-class ones, he neglects the chasm that separates the interests of both groups from the would-be oligarchs who are dictating our current government’s economic policies.

Charles Koch may have little use for well-funded public schools and universities, Social Security, Medicare, or child-care subsidies. But most upper-middle-class families do. Welfare liberalism, broadly defined, is in virtually every American’s enlightened self-interest.

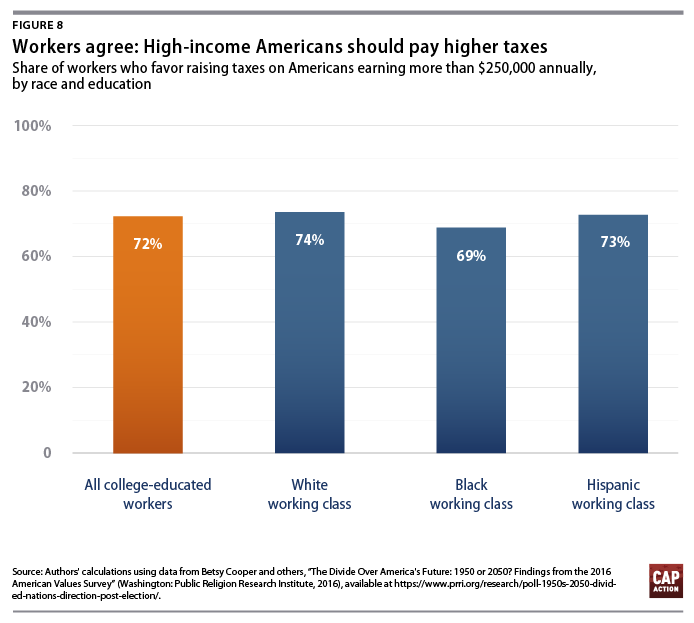

And given the insane share of national income that the top one percent (especially the top 0.01 percent) has hoovered up over the past four decades, Democrats can do an awful lot of progressive redistribution without infringing on even the narrowest material interests of the merely affluent. In fact, thanks to the Trump tax cuts, the next Democratic administration will be able to generate hundreds of billions of dollars in “pay-fors” for new social spending by simply returning tax rates on corporations and the super rich to Obama-era levels. And polling data suggests that affluent voters would be more than happy to soak the rich:

All of which is to say: Progressives should be concerned by the fact that working-class Americans are voting less than they used to — and that those who are still casting ballots are voting for Republicans more than they once did. As Edsall suggests, uniting an organized, multiracial, working class under the Democratic banner would expand the horizons of progressive possibility. But in this benighted, neo-feudal era, the left can accomplish a great deal by waging war on America’s ruling class with a coalition of the proletariat and the “woke” bourgeoisie.