In the early ’90s, Jaime Levy, a punk-rock hacker chick from Los Angeles, marched into the Tisch Building at NYU without an appointment. The move was part bombast, part desperation: She wanted to join the university’s Interactive Telecommunications Program, but didn’t think she could have gotten an interview if she tried. She wandered around the fourth floor until someone led her to the office of Red Burns, the program’s venerable chair, a bristly redheaded matriarch some called the Godmother of Silicon Alley. Jaime was intimidated, but she had only two days in the city, so she told Burns she wanted to tell stories using computers. Burns took a shine to Jaime — a kid with only a skateboard and an Amiga to her name — and gave her a full ride.

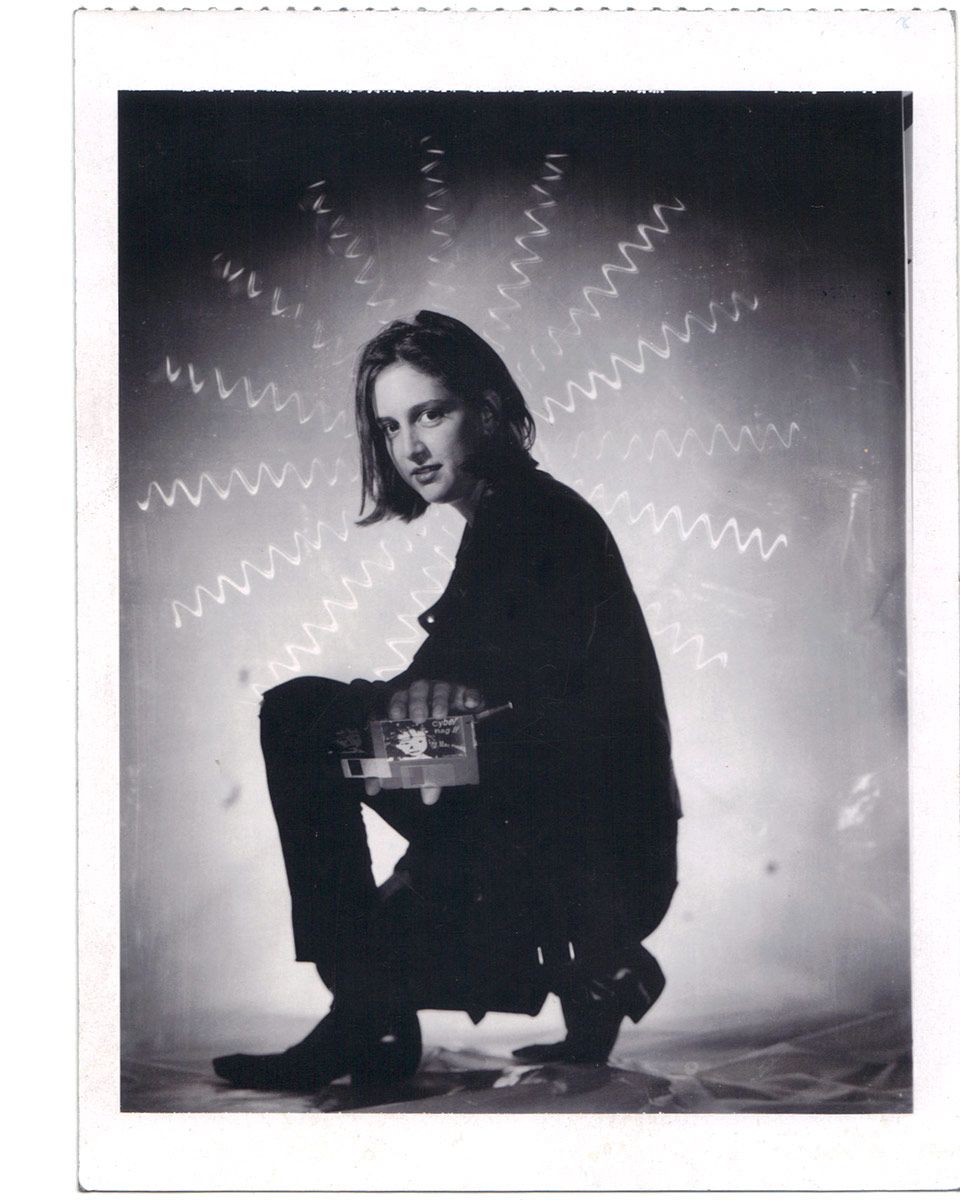

Jaime spent her years at NYU experimenting with interactive media. For her master’s thesis, she combined the do-it-yourself ethos of punk with the emerging possibilities of desktop publishing, producing an electronic magazine, Cyber Rag, on floppy disk. With color-printed labels Krazy Glued onto each “issue,” Cyber Rag looked the part of a punk-rock fanzine. Loaded onto a consumer Mac, its stories came to life with images pilfered from the Village Voice, the Whole Earth Review, Mondo 2000, and Newsweek, collaged together onscreen as though they’d been xeroxed by hand. Cyber Rag was the first publication of its kind, built with Apple HyperCard and MacPaint. Along with her animations, Jaime added edgy interactive games (in one, you chase Manuel Noriega around Panama), hacker how-tos, and catty musings about hippies, sneaking into computer trade shows, and cyberspace.

After grad school, Jaime moved back to Los Angeles and renamed her magazine Electronic Hollywood. Although she had a day job as a typesetter, she distributed Electronic Hollywood to indie book and record stores, where they routinely sold out. The novelty got her national media attention, which she leveraged into mail-order sales. After her magazines were featured in an issue of Mondo 2000, the cyberculture’s magazine of record, she was flooded with orders and fan mail. Although she made only five issues, she sold more than 6,000 copies at six bucks a pop — not bad for disks that cost less than 50 cents to produce.

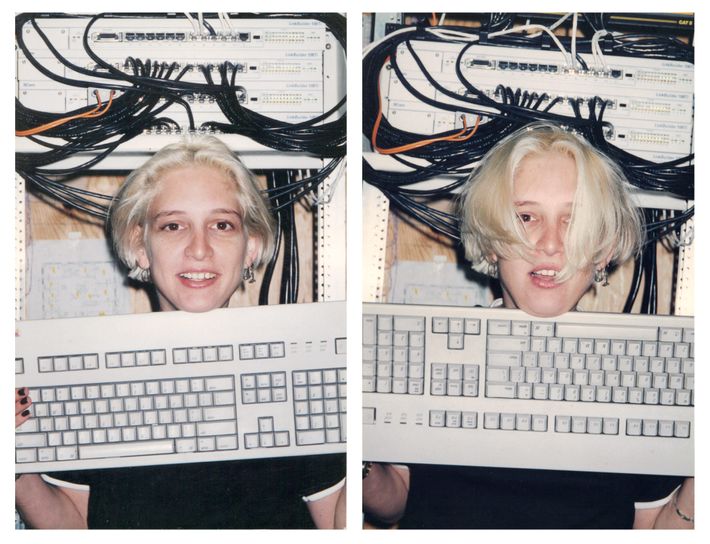

When Jaime finally moved back to New York, she became Silicon Alley’s first real celebrity, a poster girl for a new generation of 20- something media titans ready to reboot the world. With peroxide-blonde hair, she was the self-styled “Kurt Cobain of the Internet,” and a hacker through and through; in her loft, a TV screen doubled as her Mac monitor, and a flashing red light, the kind usually reserved for the hearing-impaired, signaled incoming calls over the din of her stereo. Anyone who was anyone in the emerging tech counterculture had copies of Cyber Rag and Electronic Hollywood — even Billy Idol, the British rock star, was a fan. Idol loved Jaime’s floppies and decided he needed one for his album, Cyberpunk. They worked out a deal: For $5,000, Jaime would make Billy Idol an interactive floppy disk of his own. “He just really wanted to party with me,” Jaime remembers. One night, at Los Angeles’s infamous Club Fuck, they got so wasted that Billy threw her across the table and broke her arm. “I was supposed to be animating his disk. I had to, like, do the whole thing with my non-mouse hand.”

Idol’s album flopped, but Jaime kept her rep as savvy netizen. She got a straight job, commuting to White Plains to do “bonehead interface design” at IBM — in her baggy plaid shirts, she was often mistaken for a janitor. A co-worker at IBM showed her Mosaic, the first browser for navigating the World Wide Web. She experienced it as a conversion: Her electronic magazines were websites, before websites existed, with hypertext navigation and “pages” of sound, video, and text. “Once the browser came out, I was like, ‘I’m not making fixed-format anymore. I’m learning HTML and that was it.’” She quit her day job.

Around that time, Jaime started hosting parties in her Avenue A loft. She called them “CyberSlacker” parties, updating the Gen-X honorific for the wired generation. CyberSlacker was the first of the Silicon Alley parties. Within a few years, the flush of dot-com money in New York would turn the Flatiron district into a bacchanal of rare proportions. Multi-million-dollar start-ups with names like Razorfish and DoubleClick burned their IPO money on go-go dancers and vodka pyramids as their CEOs became celebrities, their risqué party pictures leaping from the Silicon Alley Reporter to “Page Six.” The most infamous of the Alley parties were funded by an early web-streaming company, Pseudo, whose CEO, Josh Harris, was notorious for bringing together tech socialites, hungry entrepreneurs, artists, musicians, and New York club kids in increasingly extravagant environments. “Josh Harris always says he didn’t copy me,” says Jaime, who would never have his resources, “but it’s impossible that he didn’t.”

Many people saw the web for the first time in Jaime’s loft, on a Mac II her hacker friend Phiber Optik set up with a 28.8K internet connection. As avant-garde guitarist Elliott Sharp performed live, and another friend, DJ Spooky, played house tracks, Jaime’s guests gathered around the Mac’s small screen. At the top of 1994, there were fewer than 1,000 websites in the world, mostly personal home pages. These converts would call themselves the “early true believers,” counting the year of their arrival online as a mark of status, the way the first punks claimed 1977. Soon after the bubble popped, a New York Magazine story about Jaime and her peers nailed the time line: “Nineteen ninety-five is cool. Nineteen ninety-six or early 1997 is all right. Anything after that is not. Two thousand makes you a real loser — a suit, a kid just out of college, a fiftyish businessman looking for one last hurrah and another hundred million dollars.”

In 1995, a software company called Icon CMT tapped Jaime, then at the height of her fame, to be the creative director of a new online magazine called Word. The budget was good, or at least more than nothing, which is what Jaime had in the Cyber Rag days, and it was early days: Jaime had the opportunity to set a standard for what publishing could do with this new medium. The last thing she wanted was for Word to feel trendy, like Billy Idol’s failed foray into cyberpunk.

Thanks to Jaime’s initial mandate for interactive design and some choice early hires—including art director Yoshi Sodeoka—the site came to define the possibilities of online publishing. Here are a few things you might have found on Word.com, circa 1998: Word’s chat bot, Fred the Webmate, a pixelated, misanthropic New Yorker you could talk to by typing questions (Fred was damaged, with sexual issues he often alluded to but never addressed, and if pressed, he claimed to have been recently laid off by a large new media company). An interactive game in which the objective is to pop zits. Meaningless interactive toys, like a cartoon microwave you drag a dog into. At least one first-person account from someone who got a coffee enema. The formula worked: By 1998, Word was logging 95,000 daily page views, and 1 million to 2 million hits a week. When the New York Times ran its first article explaining the web browser to its readers, it used Word.com as an example.

At the tail end of 1996, Jaime Levy threw her last CyberSlacker party. In the escalating fever of the dot-com boom, it was hard for her to stay centered. She wandered away from Word after a year and a half to pursue freelance contracts on her own. Not long after, in a business move only possible at the height of the bubble’s speculative delirium, Word was bought for $2 million by a holding company that specialized in the production of industrial-grade fish meal.

Jaime had assumed that when she left the magazine, she’d find another high-paying creative gig, but the landscape had changed. As she tried to scrap together freelance gigs, her annual salary plunged. She spent a year designing Malice Palace, a dystopian chat room based in a postapocalyptic version of San Francisco, decorating it with images of burned-out tech companies, radioactive burritos, and zombie drug pushers. To her great misfortune, she founded her own company, a digital production studio called Electronic Hollywood, on the eve of the stock-market crash. “Something was coming to a head,” she remembers. “It had already been too many years of too much money for no business model, no return on investment.” At 34, Jaime moved back to Los Angeles. She got an apartment in Silver Lake and a car. She started over. The stink of the crash was on her, and when she started applying for jobs again, she omitted from her résumé her tenure as the CEO of a dot-com. Instead, she told interviewers that she’d been a front-end designer at her own company.

When Zapata, the fish-meal processing company, finally shut down Word, it did so very quickly. Jaime had stolen a backup the last time she was in the building, but she got “fucked up and left it on the subway.” At this point, Word has been off-line far longer than it was ever online. Jaime Levy’s floppies are sitting in her home office, although she’s getting them restored and hopes to show them in a museum someday. But her work is just as important as the fortunes made and lost in the feverish speculation that transformed the web from an academic swap session to the beating economic and cultural heart of our world.

She didn’t get rich, and much of what she built has been erased in the slow erosions of the web or else is bound to media inaccessible to anyone but digital archivists with the means to replay them. This makes her achievements difficult to remember, but it doesn’t make them any less significant; her efforts are artifacts, as the web is a dynamic artifact, an endless conversation writing over itself again and again in the soft echo of the boom.

*Adapted from Broad Band: The Untold Story of the Women Who Made the Internet (Portfolio, 2018).

Broad Band author Claire L. Evans will appear in conversation with Jaime Levy and Stacy Horn, the founder of EchoNYC, an early social network, at the New Museum on Thursday, April 19, at 7 p.m., presented by Rhizome.org. For more info and tickets, click here.