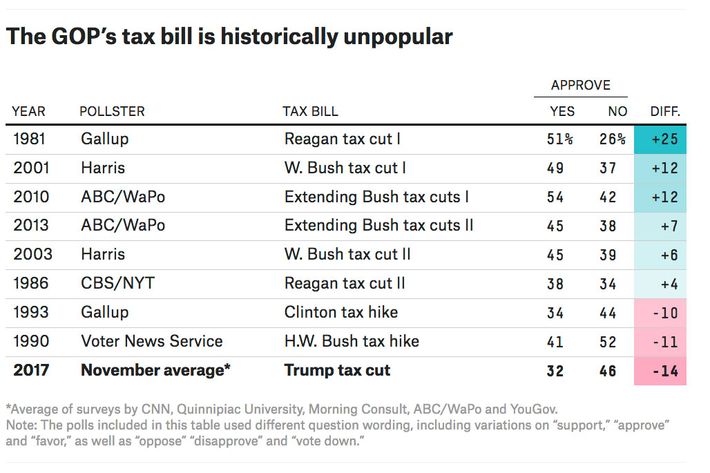

Between 1980 and 2016, the American public never met a tax cut it didn’t like. In the decades between Ronald Reagan’s election and Donald Trump’s, Congress passed major, tax-reducing legislation six times — and on each occasion, a plurality of voters were onboard.

And then, America met the Trump Tax Cuts. When Congress passed the president’s signature legislation in December, it was the least popular tax bill in modern American history — a measure even less popular than the tax hikes passed under George H.W. Bush and Bill Clinton.

For American conservatives, this was a harrowing development. It was one thing for the public to disdain the GOP’s attempts to pare back Obamacare — retrenching the welfare state has always been the sour note in the right’s paean to “small government.” But if fiscal conservatives can no longer sell voters on across-the-board, deficit-financed tax cuts — untainted by any simultaneous attack on the safety net — what are they so supposed to sell them?

Initially, Republicans took solace in the thought that their bill’s unpopularity was merely the product of Democratic duplicity. After all, as of late last year, only about one-third of voters said that they expected the legislation to lower their taxes — even though the bill is expected to reduce the tax burdens of roughly 80 percent of U.S. households. Surely, Americans would love the Trump tax cuts once they got to know them. The proof would be in the paycheck — and, failing that, in a multimillion-dollar Koch-funded ad campaign.

Alas: Americans have now been collecting post-tax-cut paychecks for more than two months — and they still don’t like Donald Trump’s signature legislative achievement. In fact, as Republicans fan out across the country Tuesday for “Tax Day” rallies celebrating their law, the vast majority of voters still refuse to accept that their taxes have even gone down. But don’t take my word for it — take the American Enterprise Institute’s. In a new polling analysis, the right-wing think tank concedes that “overall opinion [of the Trump Tax Cuts] is still more negative than positive,” while an overwhelming majority of Americans say that their paychecks haven’t grown conspicuously fatter.

The most recent poll on the legislation is particularly grim: This month, NBC News and The Wall Street Journal found that the tax cuts have grown more unpopular since taking effect, with just 27 percent of Americans calling the legislation a “good idea,” and 36 percent deeming it a “bad one.” What’s more, just 39 percent of the public expects the tax cuts to have a “positive impact” by strengthening the economy and growing jobs — while 53 percent foresee a negative impact from “higher deficits and disproportionate benefits for the wealthy and big corporations.”

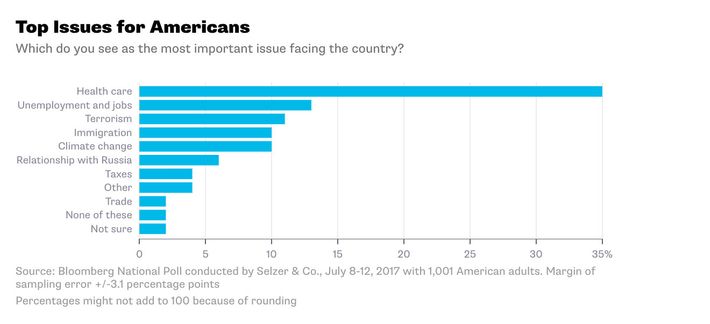

In its analysis of the tax law’s reception, AEI offers its donors the following note of consolation: “[T]hese early soundings may mean very little. Taxes rarely rank high as top voting issues. The economy’s performance could be more important for voters.”

This is a sound enough argument for why Republicans may avoid paying a significant price for their unpopular tax law. But that’s almost beside the point. The GOP has already resigned itself to a rough midterm. The public’s antipathy for the Trump Tax Cuts is less of a threat to conservatives’ near-term electoral goals than to their long-term ideological project. And AEI’s analysis offers no solace to those concerned about the viability of the latter: The fact that Americans do not rank taxes as a top voting issue is not good news for a movement whose only remotely popular fiscal policy idea is tax cuts.

If voters do not believe that across-the-board tax breaks have positive economic benefits — and resent tax cuts for the rich more than they appreciate ones for themselves — then it’s going to be nigh-impossible for conservatives to realize their “small government” vision on the federal level.

On Meet the Press last Sunday, Paul Ryan (unintentionally) explained why this is the case. When Chuck Todd asked the supposed “deficit hawk” to explain why the national debt had swelled during his speakership, the House Speaker replied:

The baby boomers’ retiring was going to do that. These deficit trillion dollar projections have been out there for a long, long time. Why? Because of mandatory spending which we call entitlements…Mandatory spending which is entitlements, that goes to $2 trillion over the next decade. Why does it go to $2 trillion? Because the boomer generation is retiring. And we have not prepared these — these programs. So really, that’s where the rubber hits the road. I think the most irresponsible Congress is the one that created brand a new entitlement. That to me is, is the big mistake. And we can fix these programs and still meet the mission for them. But the way they’ve been designed in the 20th century doesn’t work.

The most obvious problem with Ryan’s response is that it’s an unabashed lie: After observing the initial effects of the Trump Tax Cuts, the Congressional Budget Office predicted last week that the legislation will single-handedly add $1.85 trillion to the deficit over the next decade.

But a more fundamental flaw in Ryan’s argument is that — to most Americans — it reads like a case against tax cuts. If an unavoidable, demographic change is making it more expensive for the government to meet its obligations to retirees, then why on Earth did Republicans make reducing revenue their top legislative priority? Ryan’s position is only coherent if one stipulates a bogus economic premise (that tax hikes inevitably lose revenue by sapping growth) or a freshly debunked political one (that voters will prioritize low tax-rates over the survival of popular government programs). Further, to the extent that Social Security’s “20th century” design “doesn’t work,” it is because the program is too austere, not too generous. The collapse of private-sector pensions — along with the failure of wage growth to keep pace with the rising costs of health care, housing, and higher education — have left Americans more dependent on Social Security benefits for their retirements, not less: As of 2016, nearly half of U.S. families had no retirement account savings at all, according to a report from the Economic Policy Institute (EPI).

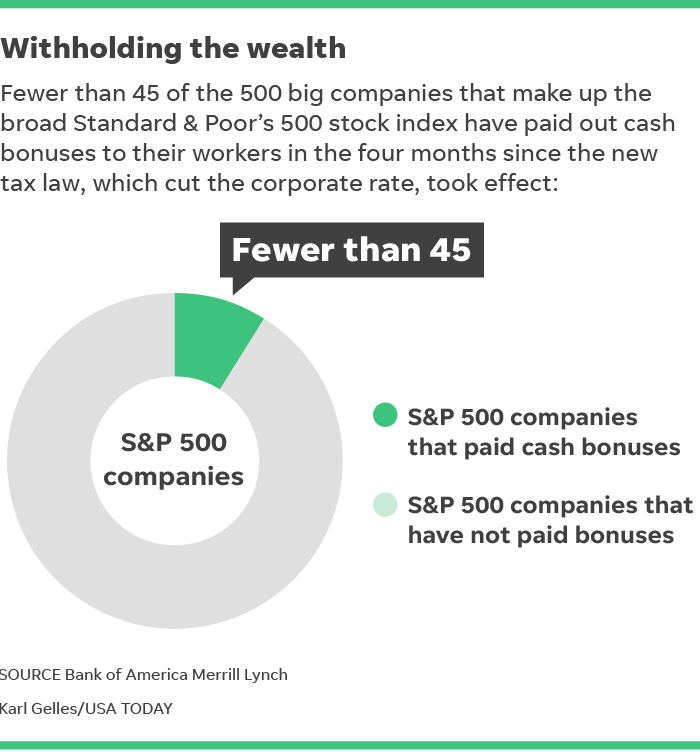

Fearmongering about the deficit only works as an argument for the conservative agenda if the public believes that they have an overriding interest in keeping taxes (on everyone) low. But the public does not believe that. And the Trump Tax Cuts have done nothing to convince them otherwise. Contrary to the GOP’s perennial promise, the benefits from corporate cuts aren’t trickling down. Wage growth is tepid; stock buybacks are soaring.

Last spring, 61 percent of Americans told Gallup that their income-tax burden was already “fair” – while just 4 percent told Bloomberg that “tax policy” was the most important issue facing the country. Meanwhile, large majorities of the public — including, in one Morning Consult survey, a majority of self-identified conservatives — voiced support for increasing federal health-care spending.

There was no popular outcry for “middle-class tax cuts” in 2017 — let alone, for giant corporate cuts financed by reductions in health-care subsidies. The GOP assumed that voters would come around to its view on “starving the beast,” once they got their share of Uncle Sam’s rations. They assumed wrong.

Democrats are already winning elections in Red America by spotlighting the GOP’s fringe fiscal priorities. In recent weeks, striking teachers have won victories of their own by the very same method. The Koch network can afford to lose such battles. But by passing the first unpopular tax cut in modern memory, Republicans have proven themselves incapable of winning the wider war. When the “rubber hits the road” — and voters are forced to choose between maintaining entitlement benefits and keeping tax rates low — there’s never been less doubt about which they’ll choose. And this means that the conservative movement has never had more incentive to create a democracy so dysfunctional, American voters don’t get to make that choice.