On the 5oth anniversary of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination, there will as usual be many claims about his legacy, from the conservatives who have perversely turned King into an enemy of race-conscious politics to the radicals who evoke his socialist and anti-imperialist tendencies. Truly living legacies, of course, are built on people, not just ideas. So it’s important to reflect on those who have carried on King’s mission in one respect or another.

King’s most immediate activist “heirs” were, of course, those who were part of his core leadership group in the Southern Christian Leadership Council. Several went on to political careers, notably 1984 and 1988 presidential candidate Jesse Jackson and ambassador to the U.N. and Atlanta mayor Andrew Young (the late Hosea Williams also won a series of local legislative offices, but was mostly a protest figure in Georgia politics).

Congressman John Lewis was an extremely notable member of the broader group of King’s contemporaries in the civil rights movement, heading up the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee from 1963–66 and leading the Selma protests that inspired the enactment of the Voting Rights Act of 1965. He’s the most important surviving independent figure from that era.

And King’s widow, Coretta Scott King, was for decades (until her own death in 2006) a symbol of her husband’s continuing legacy, and was the founder of the King Center in Atlanta that ensures his memory will endure.

Beyond those obvious “heirs,” though, King’s mantle has always been a matter of some dispute. Those who think of his main accomplishment as the destruction of Jim Crow might well view him as a regional redeemer, whose work made possible not just African-American political participation but the emergence of southern white liberal pols like Presidents Jimmy Carter (whose ascent to the presidency depended heavily on support from King’s family and associates) and Bill Clinton. In contrast, those who view King as a global figure who was himself an heir to Mahatma Gandhi could legitimately see his legacy at work in the anti-apartheid struggle in South Africa.

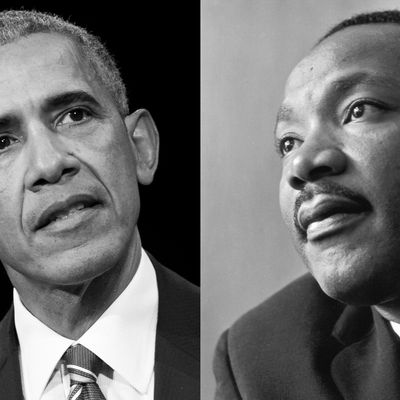

Beginning with Barack Obama’s explosion onto the national scene in 2004, though, it’s been difficult to think of anyone else more likely to serve as King’s political heir in the sense of representing the destruction of a barrier to African-American accomplishment that few thought would fall so quickly. Some of King’s own comrades-in-arms viewed Obama’s election as president as the reward for their own sacrifices. John Lewis memorably said that “Barack Obama is what comes at the end of that bridge in Selma.” And in 2007, as reported by David Remnick, Obama himself captured his relationship to the civil-rights movement with a Biblical metaphor he offered at a church service — in Selma.

From the pulpit, Obama paid tribute to “the Moses generation”—to Martin Luther King and John Lewis, to Anna Cooper and the Reverend Joseph Lowery—the men and women of the movement, who marched and suffered but who, in many cases, “didn’t cross over the river to see the Promised Land.” He thanked them, praised their courage, honored their martyrdom. But he spent much of his speech on his own generation, “the Joshua generation,” and tried to answer the question “What’s called of us?”

As we now fully understand, Obama’s election represented a “Promised Land” for race relations only in the narrowest sense. Aside from his own self-imposed limitations as a calm and cautious politician, his election inspired — and continues to inspire — a white backlash that ultimately helped lift to the presidency a man whose big political breakthrough was via the twisted belief that Obama was not even American. More and more, Obama looks like a Moses who led his people out of the wilderness but could not taste the milk and honey of full equality.

But if the “Moses generation” from John Lewis to Barack Obama is still with us, who will represent the “Joshua generation,” the next and more successful heirs to MLK?

That’s very hard to say. In the arena of conventional politics, Obama’s success means that another black president isn’t so astonishing an idea, particularly given the Democratic Party’s heavy reliance on minority voters and African-Americans’ own dominant position in so many key Democratic primaries after Iowa and New Hampshire. Looking toward 2020, Senators Kamala Harris and Cory Booker are legitimate possibilities. And if Democrats grow desperate and need a larger-than-politics “savior” to bring down Donald Trump, perhaps the likeliest object of a draft is African-American billionaire Oprah Winfrey.

Beyond conventional politics, grassroots civil-rights agitation, aimed especially at mass incarceration and police brutality, and emblemized (if hardly encompassed) by the Black Lives Matter movement, has revived something of the simmering, uncontrollable nature of the civil-rights movement, which King managed somehow to lead if not direct. While these efforts have some clear influence on left-of-center politicians (while providing targets for some right-of-center politicians, just as civil-rights activists did in King’s day), it’s unclear how and whether they will achieve a truly transracial breakthrough moment in American public life.

For the moment, the leader who most clearly carries on King’s protest legacy is another southern clergyman: North Carolina’s William Barber II. His Moral Mondays movement opposing a broad range of reactionary policies emanating from his state’s dominant Republican Party began on the 50th anniversary of the 1963 March on Washington led by King and Lewis (along with A. Philip Randolph, Whitney Young, James Farmer, and Roy Wilkins); in turn it has inspired similar protests elsewhere. Barber’s targets are naturally broader than King’s, encompassing discrimination against women, immigrants, and LGBTQ folk, and his goals extend to universal health care and environmental protection. But the ever-frustrated fight for full voting rights remains front and center for Barber and his colleagues.

But it’s what Barber is planning for next month that most definitively represents King’s legacy: a relaunching of the Poor People’s Campaign that King was planning when he died, and that was carried on under the leadership of his colleague Ralph David Abernathy, but with at best mixed results.

Starting May 14, clergy, union members, and other activists will take part in the events in about 30 states, targeting Congress and state legislatures. Then, on June 23, organizers plan a large rally in Washington — similar to what King had envisioned ….

Aside from mobilizing voters, Barber said the revived campaign will call attention to poverty, racism, and environmental issues. Organizers plan to release a study later this month on poverty in America over the past five decades.

All of King’s legitimate heirs share an understanding that the civil-rights movement was at best a partial success, and that remembering it doesn’t just mean holding commemorations or building monuments, well deserved as they are. Martin Luther King Jr. was a preeminently a troublemaker who hoped one day to become a peacemaker. That is an approach which is as relevant today as it was when King was gunned down in Memphis a half-century ago.