When historians — or, really any of us — look back at President Trump’s ascent to the presidency, they will identify many moments over the years, big and small, that could be identified as warning signs of the catastrophe to come. There was the Great Recession, the aftereffects of which hollowed out communities that thrilled to Trump’s nativism. On a much more micro scale, there was the White House Correspondents Dinner in 2011, where Trump was ritually humiliated by Seth Meyers and Barack Obama, perhaps fueling the white-hot rage behind his White House bid.

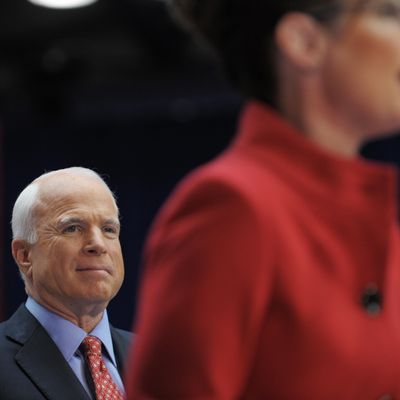

But in purely political terms, one other moment leaps to mind: the day in 2008 when John McCain upended expectations by picking then-Alaska governor Sarah Palin to be his vice-presidential running mate. It’s not as if Republicans hadn’t worn the badge of anti-intellectualism before (see: Ronald Reagan, George W. Bush). But Palin personified a dangerous new strain. She (infamously) didn’t read much; put forth few policy positions beyond “drill, baby drill”; excelled at whipping up crowds into a frothing frenzy; and attacked Barack Obama in brazen, personal terms. Stylistically, she seemed to be almost completely at odds with McCain, a deeply conservative traditionalist who prefers military wars to cultural ones.

But by and large, the GOP base adored Palin. Its loving embrace of such an unhinged figure was an early sign that the Republican Party was far more willing to tolerate qualities once thought to be disqualifying for public life than many people understood.

Throughout the campaign, and since, McCain has steadfastly defended Palin. But in a story reported from his Arizona ranch, where the senator is relaxing between treatment for brain cancer and receiving old friends during what may be his final days, the New York Times reports that McCain does have regrets about his VP pick. The reason for his discontent — which he has elaborated on in an upcoming book and movie — is that he wishes he had trusted his instincts and picked Joe Lieberman instead.

While he continues to defend Ms. Palin’s performance, Mr. McCain uses the documentary and the book to unburden himself about not selecting Mr. Lieberman, a Democrat-turned-independent, as his running mate.

He recalls that his advisers warned him that picking a vice-presidential candidate who caucused with Democrats and supported abortion rights would divide Republicans and doom his chances.

“It was sound advice that I could reason for myself,” he writes. “But my gut told me to ignore it and I wish I had.”

Setting aside Joe Lieberman’s many faults, before the 2008 election and since (and the fact that McCain-Lieberman would be unlikely to perform better among voters than McCain-Palin did), it’s striking that, even at this late stage, McCain won’t admit that Palin represents the same variation of grievance politics he now abjures.

McCain, who President Trump has taunted in grossly personal terms (“I prefer war heroes who weren’t captured”) has been one of the few Republicans to consistently take on the president. He has attacked Trump’s “spurious, half-baked nationalism” and furiously criticized his continuous praise of Vladimir Putin. And while he often votes for the president’s priorities, making his everlasting “maverick” label something of a joke, he was the deciding “no” to kill Obamacare repeal in the Senate, an act of apostasy that has earned Trump’s perpetual ire.

But McCain is not just unpopular with the far right because of his #resistance moments. He’s also out of sync with the GOP base in most other ways. He’s a national-security hawk in a time of Republican isolationism, a centrist on immigration in a party full of America Firsters. Beyond his policy positions, McCain is out of step in another important way: he wants Republicans to step back from the toxic, grievance-based ideology that now dominates the party.

Before he helped torpedo the GOP health care vote last summer, McCain gave a stirring speech on the Senate floor, pleading with his fellows lawmakers to return to a politics of decency and consensus.

“I hope we can again rely on humility, on our need to cooperate, on our dependence on each other to learn how to trust each other again and by so doing better serve the people who elected us,” he said. “Stop listening to the bombastic loudmouths on the radio and television and the Internet. To hell with them. They don’t want anything done for the public good.”

McCain framed the problem as a bipartisan one. But it’s the Republican party where “the bombastic loudmouths” have really gained control in recent years, culminating in the party’s surrender to President Trump. John McCain has always called himself a maverick, but he’ll end his life as all but an outcast.

It is facile to draw a straight line from Palin to this sad state of affairs. But it is striking that, even now, McCain cannot, or will not, fully reckon with the forces he helped unleash.