Update: Kennedy announced his retirement on Wednesday afternoon.

With the Supreme Court wrapping up its 2017 term this week, the possibility that one (or more) of the nine justices might announce their retirement has come up again. The voluntary relinquishment of a lifetime appointment to the nation’s most powerful court is inherently a very big deal. With the court near ideological equipoise, and the White House and Congress controlled by a political party that has made the transformation of constitutional law central to its bond with its most important constituency, a SCOTUS retirement could blot out the sky and cast yesterday’s political and policy obsessions into the shadows.

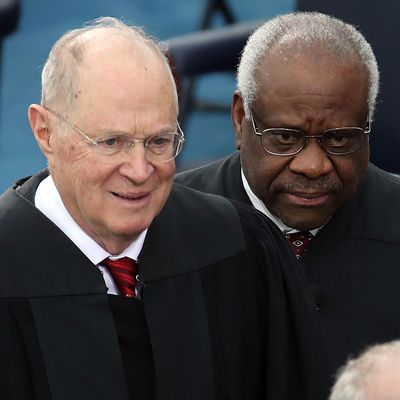

This scenario hinges on the departure in question being that of the Court’s perpetual “swing vote,” Anthony Kennedy, the 81-year-old jurist considered most likely to be mulling retirement after 30 years. (The oldest Justice, 85-year-old Ruth Bader Ginsburg, has made it clear she won’t retire any time soon, particularly while Donald Trump is president.) The very thought of a Kennedy retirement is an aphrodisiac to conservatives, particularly those focused on rolling back the abortion and gay rights precedents with which Kennedy is conspicuously identified. In March, days of headlines about “Kennedy retirement rumors” popped up in conservative media after Senator Dean Heller mused aloud that a SCOTUS vacancy would be helpful in firing up the GOP base in 2018 Senate races like his own. There was no fresh evidence that Kennedy was actually going to hang it up, but it’s as though Republicans were trying to will him into retirement.

Other than his advanced age and some scattered indications that he’d like to enjoy some golden years in relative leisure, the main reason Kennedy might choose to retire at this juncture is to reward the political party that first placed him on the Court with the power to choose his replacement — even though many members of that party devoutly wish for his tenure to end immediately. An academic study noted the historical pattern:

[A] 2010 study of a large sample of retirements by Supreme Court justices from 1789 through 2006 reported that when the current president was of the same party as the president who nominated the justice, and the president was in the first two years of his term, that justice was about 2.6 times more likely to retire than when these two conditions were not met.

On the other hand, several recent Republican-appointed Justices (Harry Blackmun, John Paul Stevens, and David Souter) who were at ideological odds with their partisan brethren chose to step down during a Democratic presidency. No one knows for sure what Kennedy intends to do, and when, if ever, he might elect to retire.

At least one knowledgeable observer, election law expert Richard Hasan, thinks Kennedy has been phoning it in on the big decisions of the current term, and may be signaling he’s ready to wrap up his career:

It appears that this will be the first term since he’s become a swing justice where he did not side with the liberals in one significant 5–4 case. He’s returned to his conservative roots and has given up decisively bucking his own party. The separate concurrence in the travel ban case felt to me like a Kennedy mic drop. He’s done all that he can do to fix the problems in American society. Now it’s up to those in power, and those who put them there.

If a Kennedy retirement does happen this year, the first question would be whether President Trump and Republican senators would try to rush a replacement through the vetting and confirmation process in 2018, before a possible change to the Senate’s composition due to the midterms. In May, Senate Judiciary Committee Chairman Chuck Grassley publicly encouraged potential SCOTUS retirees to make their intentions known quickly because it would take “50, 60, [or] 70” days to confirm a nominee. That’s actually very optimistic, particularly given the certainty of dilatory tactics by Senate Democrats who are still justifiably angry about Mitch McConnell’s denial of a confirmation vote to Obama nominee Merrick Garland. If Kennedy retires and a confirmation vote on a replacement by the current Senate isn’t in the cards, then the 2018 Senate races would become holy war for both parties seeking to control the future direction of the Court. The strong possibility that another Trump appointment could provide a fifth vote to reverse or significantly modify Roe v. Wade would be enough to make this a huge issue in every competitive Senate race.

A Kennedy retirement would also make confirmation of a successor, whenever it occurs, a white-knuckle affair. During last year’s confirmation of Neil Gorsuch, every Republican senator (plus three Democrats) voted to confirm him. But if the next confirmation becomes broadly understood as a vote on maintaining or reversing recent Kennedy-supported decisions like Whole Women’s Health v. Hellerstedt (which confirmed a constitutional right to an abortion with a prohibition on government actions that place an “undue burden” on the exercise of that right) or Kennedy-crafted decisions like those recognizing same-sex marriage rights, there would be hellish pressure not only on Democrats but on socially moderate Republicans like Susan Collins and Lisa Murkowski to stop a judicial counterrevolution. The Federalist Society–dominated vetting system Trump put in place even before his election as president would guarantee a fifth unimpeachably conservative nominee, but any hint of doubt about a prospect’s opposition to abortion rights might be enough to sink any such nomination before it occurs.

The other possibility that lurks in the background is that it won’t be Kennedy retiring imminently, but the Court’s arch-conservative, Clarence Thomas, who is widely thought to be weary of Court duties after more than a quarter-century of service. A 2016 report that Thomas would retire that year was publicly repudiated by Thomas’s wife Ginni, a prominent conservative activist in her own right. But with a Republican president in office, and the possibility of Trump being replaced by a Democratic president in 2020, Thomas could decide it’s now or never for a relatively early retirement (he just turned 70 last week).

The politics of a Trump-appointed successor to someone like Thomas would be, of course, entirely different from the Kennedy retirement scenario. In some respects the dynamics would resemble Scalia’s replacement by Gorsuch, but it would be complicated by two factors. First, there’s Thomas’s race; he succeeded Thurgood Marshall, and appointment of anyone other than another African-American would end a half-century of black representation on the Court, which isn’t a good look for an administration as racially suspect as Trump’s. Second, there’s Thomas’s extreme version of constitutional “originalism,” which has made him a frequent right-wing outlier on an already conservative Court. Jeffrey Toobin calls Thomas “arguably the most conservative Justice to serve on the Supreme Court since the 1930s,” and the choice of a successor to him could expose some intra-conservative difference of opinion on constitutional law.

I won’t even go into the bizarre fantasyland that would spring to life if there were dual retirements. But even if the end of the term and the end of the year pass without any changes in SCOTUS membership, the big fight over cultural issues that has been brewing in Court-watching circles since Trump’s election will probably arrive at some point before 2020. And at that point we could see a battle reminiscent of FDR’s threat to “pack” the Supreme Court that was blocking his New Deal agenda by expanding the number of Justices, which resulted in a national crisis.