In recent weeks, as a new wave of Central American asylum seekers arrived at the U.S. southern border — and the Trump administration set about willfully traumatizing their children — two popular myths about immigration politics in the United States came back into fashion.

The first myth is that the American electorate’s embrace of Donald Trump, and the Republican Party’s broader adoption of xenophobic populism, were both products of the federal government’s persistent failure to secure our nation’s borders. The second, related fiction, is that Democrats can reduce support for nativist demagoguery — and regain many an Obama-to-Trump voters’ trust — by proving their bona fides as border enforcers.

“Donald Trump was elected in great part because of the crisis on the border in 2014 and 2015,” The Atlantic’s David Frum recently asserted, in a column that advised Democrats to enforce the border humanely. “When Trump promised a wall on the border, this was the problem that the wall was supposed to resolve.”

Pascal-Emmanuel Gobry offered The Atlantic’s readers a similar take, arguing that, while most Americans oppose Trump’s family separation policy, many “might regard Democrats as just as extreme as Trump” on questions of immigration; after all, six in ten Americans tell pollsters they want increased border security. Therefore, to regain the public’s faith — without abandoning their party’s commitment to mass legal immigration and the humane treatment of the undocumented — Gobry advises Democrats to follow the lead of French president Emmanuel Macron, and show the electorate that they “can actually be tough on illegal and irregular immigration.”

These analyses are superficially plausible, but fundamentally misguided. In truth, the nativist turn in American politics has not been driven by the public’s concerns about border security, per se, but rather by widespread anxieties about rapid demographic change. And that change cannot be reversed — or even meaningfully slowed — by reducing illegal immigration.

The Democrats’ chief liability with (white, non-college-educated) swing voters on immigration, meanwhile, is not that the party failed to secure the southern border during Barack Obama’s time in office. Rather, it is the fact that the Democrats rely on overwhelming support from nonwhite and foreign-born voters — and consequently, tend to frame the growing diversity of the United States as a positive development. These facts make it fairly easy for Republicans to portray Democrats as agents of unwanted demographic change — ones who cannot be trusted to prioritize the interests of middle-class whites over those of foreigners.

For these reasons, there is a plausible argument that Democrats should strike moderate notes on immigration, rhetorically. For example, it might be politically wise for the party to render its critique of immigration enforcement under Trump in both humanitarian and security terms — say, by pointing out that every resource ICE uses to round up law-abiding, undocumented people is one that the federal government didn’t use to combat all the criminal cartels that Trump loves to promote on social media.

But there is little reason to believe that the Democratic Party would derive any significant political benefit from taking a right turn on border-enforcement policy — not least because, if engineering a dramatic reduction in illegal immigration through draconian means could solve the Democrats’ political problems, then their problems would already be solved.

The rise of the nativist right in the U.S. coincided with a steep decline in illegal immigration.

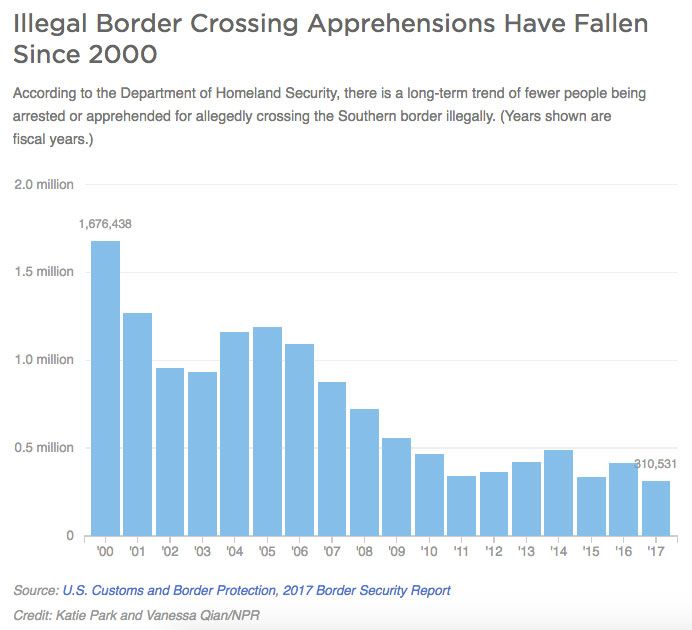

In the first year of this millenium, the U.S. government arrested immigrants for crossing America’s southern border illegally 1,676,438 times. In the year of Barack Obama’s election, that figure was down to 705,005; by the time Trump took office, annual illegal border crossings had sunk to 408,870.

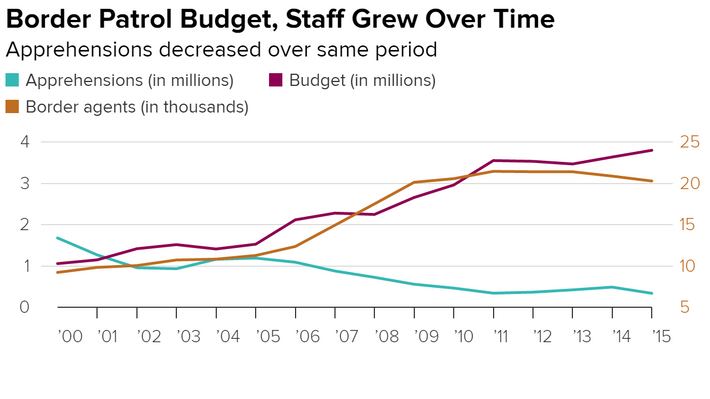

This decline wasn’t a product of weakened border enforcement; arrests did not plummet because the border had become less policed. Quite the contrary: Over the course of the Obama presidency, federal spending on border security increased by more than 37 percent; the number of undocumented immigrants in the U.S. labor force held steady; and the number formally deported by the American government skyrocketed.

And yet, over the course of Obama’s time in office, the Republican Party moved rapidly rightward on immigration — while economically liberal, culturally conservative white voters continued their steady march out of the Democratic Party.

It is hard to reconcile these facts with the premise that concerns about illegal immigration — that are rooted in objective developments at the U.S. southern border — are the primary motive force behind both the GOP’s nativist turn, and the Democrats’ struggles to retain the loyalty of Obama-to-Trump voters.

By contrast, if we stipulate that white anxiety about demographic change is driving both of those trends, the timing makes perfect sense.

The foreign-born population of the United States has increased dramatically since 2000 — rising from 31.1 million that year to 41.3 million in 2015. Today, America’s foreign-born population is more than four times higher than it was in 1970. And as America has become more foreign-born, it’s also grown much less white. During Donald Trump’s early childhood, non-Hispanic whites comprised roughly 90 percent of the U.S. population; by 2014, they accounted for just 62 percent.

That massive change in the complexion of the American public has not gone unnoticed. And there’s significant evidence that white Americans’ anxiety about such change was instrumental to Trump’s rise.

During the GOP primaries, Trump thrived in small, midwestern cities that had experienced rapid influxes of nonwhite immigrants over the first 15 years of this century. As The Wall Street Journal reported in November 2016:

[C]ensus data shows that counties in a distinct cluster of Midwestern states—Iowa, Indiana, Wisconsin, Illinois and Minnesota—saw among the fastest influxes of nonwhite residents of anywhere in the U.S. between 2000 and 2015. Hundreds of cities long dominated by white residents got a burst of Latino newcomers who migrated from Central America or uprooted from California and Texas.

… In 88% of the rapidly diversifying counties, Latino population growth was the main driver … Mr. Trump won about 71% of sizable counties nationwide during the Republican presidential primaries. He took 73% of those where diversity at least doubled since 2000, and 80% of those where the diversity index rose at least 150%, the Journal’s analysis found.

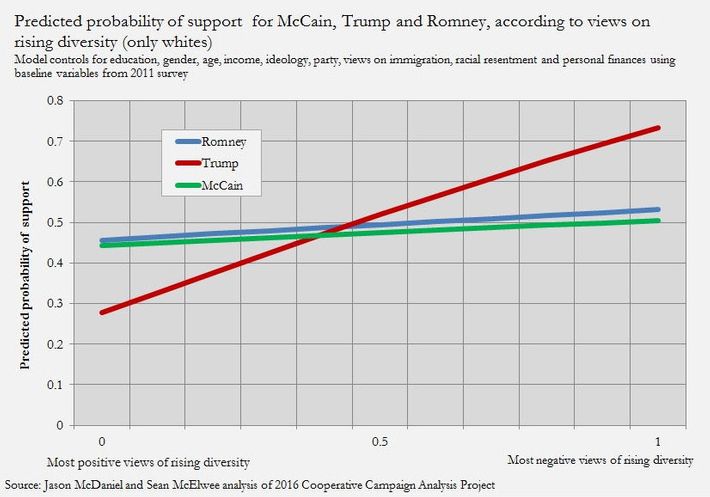

Other research suggests that negative attitudes about America’s growing racial diversity played a bigger role in determining voter behavior in the 2016 election than it had in the previous two presidential contests: Negative views on demographic change predicted support for the Republican nominee far more reliably in the Clinton–Trump race, than it did in either of Obama’s.

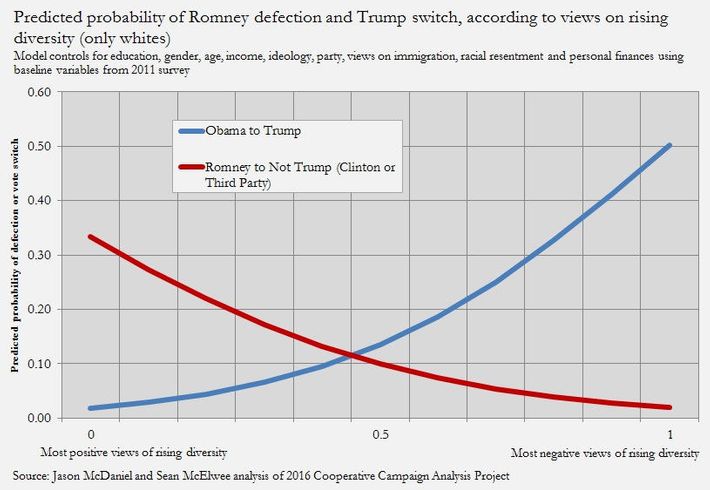

Further, the more negative were an Obama voter’s views on rising diversity, the more likely he or she was to defect to Trump’s camp in 2016. And this correlation between fears of diversification and support for Trump is further affirmed by a long list of other studies of the 2016 electorate.

This shouldn’t be surprising.

Liberals take pride in the idea that America’s national identity is rooted in creed, not ethnicity; that any immigrant, no matter their background, can become American by adopting our nation’s values. But that conception of our national identity has always competed with — and complemented — a racially defined conception of the American nation. In our country’s earliest days, European ancestry distinguished members of the polity from those whose land could be rightfully expropriated; and whose bodies justly bought and sold. And the notion that whiteness is a precondition for full citizenship was affirmed in official rhetoric and policy for most of America’s history — as was the idea that preserving a white majority was a legitimate national interest.

The authors of the 1965 immigration law — the primary cause of America’s demographic transformation — never intended for their legislation to have such an effect. In fact, they believed that their law would eliminate explicit racial restrictions from the U.S. immigration system (a diplomatic liability) while ensuring that, in practice, the system would still favor Europeans.

Given this history, it would be astonishing if the unintended, rapid diversification of the United States over the past 50 years didn’t produce a backlash rooted in white anxiety about racial demographics — especially when one adds in the fact that this diversification happened to coincide with the collapse of wage growth and upward mobility for the American middle class.

And all available evidence suggests that we need not feel astonished.

What we talk about when we talk about “illegal immigration.”

It is true that immigration hawks in the United States have traditionally focused their rhetorical and legislative energies on combating illegal immigration, rather than (forthrightly) attempting to preserve America’s status quo demography. But this does not mean that the former has been the primary motive force behind the resurgence of restrictionist politics in the U.S.

In the post-civil rights era, we would not expect a movement animated by a desire to preserve America’s white racial character to express its aims in those terms; until the rise of Trump, political norms (at the national level) rendered such appeals verboten. Rather, one would expect such a movement to take the same route that anti-black politics did in Lee Atwater’s infamous account — which is to say, one would expect it to express its animating concerns through superficially race-neutral policy appeals.

The subversion of America’s immigration laws is a phenomenon that Americans of all races can recognize as a legitimate policy problem. But it is also one that offers a permissible language for expressing racialized fears of demographic change. Republican politicians can’t say that nonwhite immigrants have no right to be in this country; that their very presence here is a threat to our national sovereignty; that they are innately disposed toward criminality; and that they should be forced to leave the U.S. en masse.

But they can — and often do — say all of those things about “illegals.”

This is not to suggest that every expression of concern about illegal immigration is a camouflaged call for ethnic cleansing; or that rank-and-file immigration hawks are all closeted white nationalists; or that their avowed complaints about illegal immigration are in any way insincere. It is only to say that most voters aren’t technocrats — ordinary Americans tend to rally behind issue campaigns that speak to anxieties and desires that are much deeper than a given campaign’s immediate policy aims (often, the most political salient anxieties aren’t even conscious ones).

And given how vigorously the Republican base opposed allowing Syrian refugees to enter the United States through legal means; how mass legal migration of ethnic minorities into European countries has provoked restrictionist backlashes that closely resemble our own contemporary one; and the tight correlation between fears of diversity and Trump support, it seems reasonable to assume that Republican voters want their president’s border wall to protect them from something larger and more abstract than just Central American asylum seekers.

For Democrats, immigration is a political problem without a policy solution.

White backlash against mass immigration is, thus, a genuine liability for Democrats in many regions of the country (even as it is a liability for Republicans in others). But that liability can’t be eliminated by securing America’s borders.

Legal immigration produced the bulk of America’s demographic changes over the past half-century — and is poised to produce virtually all of those forecast for the coming decades. This is why the Republican Party’s most overt enthno-nationlists (i.e. Congressman Steve King and White House policy adviser Stephen Miller) are so eager to slash legal inflows. And yet, even the White House’s radical immigration reform bill wouldn’t actually reverse existing demographic trends. The relatively low birthrates of white, native-born Americans are enough to ensure that this country continues to diversify in the coming decades.

All of which is to say: Survey data, history, and basic chronology all suggest that the rise of nativism in the Republican Party — and the defection of non-college-educated whites from the Democratic Party — cannot be attributed to a deepening crisis of illegal immigration. To the extent that these developments are a response to the objective consequences of immigration policy over the past two decades (as opposed to media narratives about the same), they are a response to the steady growth in America’s nonwhite, foreign-born population.

And Democrats cannot stymie such growth by rallying behind stricter rules for asylum, or more border security funding, or even Trump’s border wall. To change the objective conditions fueling Trumpism, they would need to embrace restrictionist policies even more extreme than Stephen Miller’s — a prospect that is neither ideologically nor politically tenable for Democratic officeholders.

This said, the party could try to ameliorate the subjective conditions fueling its struggles with culturally conservative whites. Democratic candidates — especially those in predominantly white, rural areas — might be wise to moderate rhetorically on immigration (or else, to say as little on the subject as possible, as Conor Lamb did in Pennsylvania earlier this year). And some such candidates would plausibly benefit from taking heterodox, hard-line positions on immigration policy (to signal their independence from their “amnesty” and “sanctuary city” loving co-partisans).

But there’s little reason to think that the Democratic Party, as a whole, would benefit from pursuing that kind of triangulation. For one thing, Democratic voters have never been more liberal on immigration than they are now (nor, for that matter, is the rest of the non-Trumpist portion of the electorate). And the Democrats have rarely been more dependent on the votes of immigrant communities — or the mobilization efforts of immigrant advocacy organizations —than they are today.

Meanwhile, culturally conservative white voters’ subjective perceptions of the Democratic Party are informed less by the reality of its policy positions, than by how those positions are represented in the media — often, in right-wing media. Thus, were Democrats to tack right on immigration policy, it is unclear whether hypothetical swing voters would even notice. After all, Barack Obama stepped up enforcement of America’s borders — and, with the help of the 2008 recession, succeeded in significantly reducing illegal immigration into the United States, even in the face of a Central American refugee crisis. And yet, this did not appear to improve his party’s standing with immigration-skeptical swing voters; nor did it prevent the GOP’s 2016 nominee from claiming that “countless Americans” who had “died in recent years would be alive today if not for the open border policies of [the Obama] administration.”

For these reasons, any right turn on immigration policy robust enough to change the Democratic Party’s image in the eyes of culturally conservative white voters would almost certainly cost Democrats an even larger number of votes through the demoralization of its base.

A better way for the party to mitigate its liability on immigration would be to try to increase the salience of pocketbook issues in the national political debate; customize its messaging and policy offerings to the idiosyncratic material challenges of individual districts in rural America; and, above all, reduce the disparity between the voter-turnout rates of white and nonwhite Americans.

In 2016, future Trump White House adviser Michael Anton warned his fellow conservatives that the “ceaseless importation of Third World foreigners with no tradition of, taste for, or experience in liberty means that the electorate grows more left, more Democratic, less Republican, less republican, and less traditionally American with every cycle.”

Democrats must work to prove Anton right.