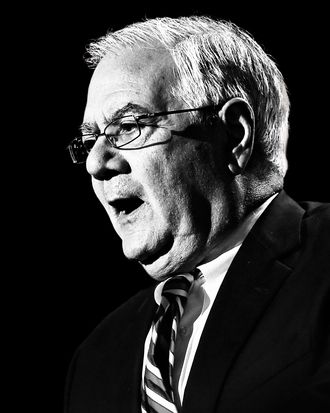

A decade now after the 2008 financial crisis, the cultural and psychological imprint that it left looks almost as deep as the one that followed the Great Depression. Its legacy includes a new radical politics on both left and right; epidemics of opioid-abuse, suicides, and low birthrates; and widespread resentment, racial and gendered and otherwise, by those who felt especially left behind. This week, New York continues our retrospective on the crash and its aftermath by publishing interviews with some of those who were closest to the events. Here, Barney Frank, the chair of the House Financial Services Committee during the Great Recession and one of the namesakes for the Dodd-Frank Act, discusses the government’s biggest failure during the recovery, the political legacy of 2008, and the current state of bank regulation.

What was the worst part of the aftermath?

Our one big failure was to help people with foreclosures. We did not do enough to help some of the innocent victims of all this. Here’s what happened: Some of the people who faced foreclosure, it was their fault. They overreached. But other people were misled, other people had reasonable expectations and then the market for their property dropped, and then there were other victims. Imagine you’re somebody who’s got a home, and you’re paying for it, and you’re in a neighborhood where there are some sketchy people — and all of a sudden they’re foreclosed on, and the bottom falls out of your property, and your neighborhood goes to shit.

So one of the big crises is that, when we did the TARP, we, the Democrats, said to Hank Paulson — with whom I get along on every other issue and admire greatly — “We need to use some of this money to help people who are the innocent victims of this to avoid foreclosure.” Paulson said, “I can’t. I need the first $350 billion for the banks. I have none left over.” We raised hell. We had a major fight about it. He then said, “Okay, I’ll ask for the second $350 billion, and if I get it, I’ll use some of the money for foreclosure.”

The problem was, this was now after the November election. He’s in a lame-duck administration. He says, “But I’m not gonna do that without Obama’s okay.” So I and others went to Obama and said, “Will you tell Paulson it’s okay to ask for the next amount, so he can do foreclosures?” Obama said what most presidents-elect would have said in that situation: “No, he has the legal authority to do it, and I’m not gonna take responsibility over something I have no control over. If he wants to do it, he can do it. We only have one president at a time.”

It made me crazy. Obama overstated the number of presidents we had — because we didn’t have any! And people were getting fucked. That was the biggest single problem. And by the way, that wasn’t just a social problem. It tainted the thing politically. It’s one reason why TARP is — I think unfairly — demonized. They paid all the money back, and it stopped worse consequences, but in fact, it was the case that in the first instance, almost all the TARP money went to banks; none went to homeowners.

One exception to that which is generally popular: The TARP money did save the auto industry. He did ask for a second chunk, finally, under Obama, but only for Chrysler and General Motors.

Could you talk about the effect on the public consciousness?

Well, it was bad, for two reasons: One, the fact that we were bailing out the banks. But it was exacerbated by the failure to do any serious foreclosure relief.

“They got bailed out, we got sold out.”

Yeah. So you really did have both the tea party and Occupy grow up at the time. The problem for us was that the tea-party people, as people on the right so often are, were very smart politically, and they organized and they registered and they voted. My, ah, sometime ideological allies at Occupy decided that the way to change things was to smoke dope and have drum circles. Neither one of those did a hell of a lot to influence my colleagues.

The other thing is, it came out in February or March of 2009 that AIG — which had received $170 billion in federal funds to pay its debtors — had paid bonuses to the very people who had caused the problem. At that point, the country went berserk. It was almost like the peasants were in the street with the pitchforks and torches. The inability, the failure to provide foreclosure money, and then the revelation that the AIG perpetrators had gotten bonuses.

The coda to all that, by the way, is that Maurice Greenberg — the former chief of AIG, who still had a lot of stock — later sued the federal government, because in giving them $170 billion to keep them in business, we exceeded our authority. I later characterized that as the arsonist suing the fire department for water damage.

So we don’t use the terms “tea party” and “Occupy” any longer, but —

Well, the tea party has changed part of its name: It’s now called the Republican Party.

What I see on the left makes me happy — which is, “Okay, we’re gonna vote too.” I was on Bill Maher’s show with a woman from Occupy, and I said, “I have to tell you, one thing that troubles me is I never saw a voter-registration site at an Occupy site.” She said, “Oh, that’s not what we’re into.” Now they are. One of the most positive developments for me is that — it took Trump to do it — but many people on the left now understand the importance of voting.

What do you think of the overall response on the regulatory side?

The pattern we’ve seen in American economic history is that the private sector innovates, and ultimately comes up with things that outstrip existing rules, and the government waits too long to come up with new rules. That’s essentially what happened here.

Financial regulation started in the 1890s, when for the first time, there’s a national economy in America. There weren’t any national businesses in 1850. So, by the 1890s, they were thinking, “Well, we’d better have some national rules.” So you have the Antitrust Acts, you have the Federal Trade Commission. They come up with a set of rules. But the one thing they didn’t do back then was regulate the stock market, because they never heard of it. It wasn’t a big deal. What happened is, the stock market gets into problems because it’s just not regulated. So what the New Deal does is to regulate finance capitalism.

That system works very well from 1941, when the last act was adopted in that package, until about 1980. In the interim, what happens is money starts coming in outside the banking system. And the other important thing that changed was information technology. You could not have securitized thousands of loans by hand. So, you had all this new money coming in from oil-producing countries and Asian countries with a lot of surplus from trade, and then the ability to securitize, until, essentially, the market crash. It’s true, Glass-Steagall was repealed. By the way, Glass-Steagall wasn’t repealed until 1999. The problem started well before that. Glass-Steagall was sort of irrelevant to the problems. It didn’t stop bad loans from being made, and it didn’t stop people from doing credit-default swaps with nothing to back them up. And, that was the problem.

What we did in 2009 and ’10 was analogous to what they did in the ’30s. We adopted a new set of rules for new financial practices that had previously not been regulated.

So is it even possible to just keep our regulations updated as the financial industry evolves? Or are periodic crashes inevitable?

We tried to do that in two ways. First of all, we created in the Financial Stability Oversight Council; that was an important thing, because it had the power to go beyond the specific jurisdiction of any of the agencies. It’s a council of all the regulators, with all their powers pooled, and the specific mandate to take action if they see a new problem.

And then, the other new thing we did, although Trump’s tried to weaken it, was to create the Office of Financial Research, precisely to look for new problems as they arise and bring them to the attention of the regulators. The regulators and the rules have sufficient flexibility, we believe, to reach out to new problems, to new practices.

If you had asked me in 1953 whether we were prepared to deal with credit-default swaps, I’d say — I was busy with my bar mitzvah, so I probably wouldn’t have had the attention to pay. Back then, I would have said, “What, what, what is that? Who? What?” So I don’t know. I can’t foresee what the innovations will be 20 years from now. But to the extent that there are incremental changes, that they find loopholes, we think that the regulators have the power now to handle those.

I was struck, recently, reading the economic report of the Federal Reserve. This is Donald Trump’s Federal Reserve, his appointees. What they say in the report is, from the standpoint of financial stability, we’re in very good shape. I think we put in a set of rules that make it very unlikely that we’re going to have another crisis, certainly not for the reasons we had the last one. We have built honest stability into the financial system without any loss of function. I mean, the odd thing is Donald Trump tries simultaneously to complain that we ruined the financial system, and to say the economy is better than it’s ever been. It would be hard to make that happen if you had ruined the financial system.

There was a lot of fear when he came in that Dodd-Frank would be gutted, whether legislatively or because of regulators refusing to enforce the rules.

It has, tragically, happened in one area: the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, with Mick Mulvaney being a thug. But in every other area, no. The single biggest grant of authority in the new law was to the Commodities Futures Trading Commission, to regulate financial derivatives. And Christopher Giancarlo, who is head of the CFTC, appointed by Trump, said, ‘I like this law.’ He has some differences on how to deal with it, but it’s remained in place.

The only politically powerful group still fighting against the bill were the small banks, the community banks. And what that law did was, frankly, to buy them off. There’s no longer any significant political opposition to the law as it stands, and that bill left 95 percent of the law in place. It did not weaken the regulation of how derivatives are conducted in any way. It still does not allow anybody to make really bad mortgages and securitize them.

So we have a law now that is not going to be changed legislatively. It has worked very well.

*A version of this article appears in the August 6, 2018, issue of New York Magazine. Subscribe Now!